A non-government organisation has complained that sustainable forestry certifier Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) has continually delayed investigating a company owned by one of Indonesia’s wealthiest families over its links to illegal forest clearing.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Jakarta-based NGO Auriga Nusantara submitted a formal complaint about Djarum Group, a cigarette maker and business empire controlled by the Hartono family, eight months ago, and the group has said that a drift in FSC’s policy could mean that rogue actors are not being properly investigated.

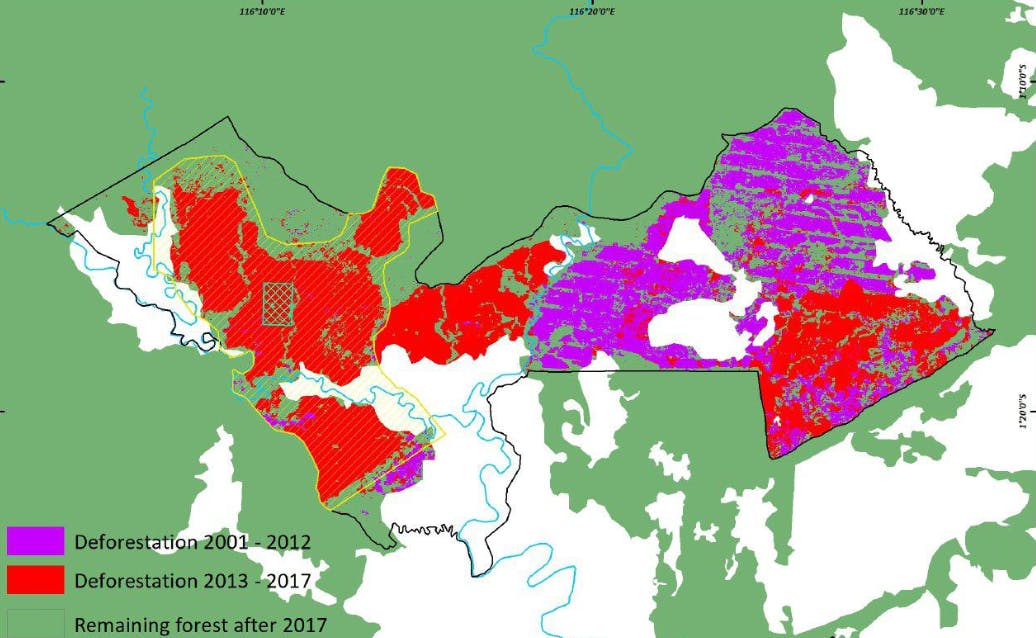

Djarum owns FSC-certified paper mill PT Bukit Muria Jaya, which has processed timber supplied by two pulpwood companies connected to the Hartono family that, according to Auriga, had cleared 32,000 hectares of rainforest in East Kalimantan between 2013 and 2017.

The pulpwood companies in question, PT Fajar Surya Swadaya and PT Silva Rimba Lestari, are alleged to have supplied two of Indonesia’s largest forestry firms, Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL), in violation of their zero-deforestation commitments. APP confirmed the deforestation and removed the supplier. APRIL denied the deforestation occurred in an area of high conversation value.

The forest clearing was documented by Auriga and other NGOs in a report published in August 2018. A follow-up report was published in October 2019. As FSC did not take any action, Auriga filed a complaint to the certification body in December 2019 for failing to uphold its own rules on deforestation.

“

Does FSC leadership want to investigate complaints and enforce its own policies?

Syahrul Fitra, researcher, Auriga Nusantara

Deforestation in the concessions of PT Fajar Surya Swadaya, from 2001-2012 (in purple) and from 2013-2017 (in red). Sources: Forest cover from Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry land cover maps from 2000 and 2015, tree cover loss from Hansen et al. 2013 with updates for 2017 from Global Forest Change.

In February this year, FSC accepted the complaint. At this point, according to FSC’s operating protocol, it has 30 days to appoint a complaints panel. The panel then has 60 days to investigate and present its recommendation to the FSC Board. But for this case, FSC opted to hire a satellite monitoring expert, saying this would speed up the assessment process.

Auriga said that the satellite assessment option would not be as rigorous as FSC’s regular procedure for handling complaints, which includes detailed deadlines and an appeals process to ensure a transparent, timely conclusion to the investigation.

In June, FSC suspended the investigation due to “resource and travel restrictions” resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Auriga has questioned this decision, saying that satellite analysis does not require site visits or field work that would involve travel.

“The cost of hiring a consultant to analyse deforestation over the last five years for an area less than 100,000 hectares is very small relative to FSC’s US$30 million operational budget,” Auriga said.

FSC told Eco-Business that Covid-19 had reduced its capacity by a half since May, depleting its ability to resource complaint investigations.

Sources familiar with the process have suggested that FSC may have delayed the complaint because it involves APRIL, a company that it is working towards reassociating with.

FSC banned APRIL from using its trademark in 2013.

The certifier said that the decision to delay the investigation and the process of reassociation with APRIL are “treated separately”.

FSC has also indicated that it is in discussions with Djarum Group to secure a public commitment to halt deforestation. Auriga said that it supports the dialogue and encourages Djarum to initiate a zero-deforestation policy, but these discussions are “not a substitute” for a formal investigation.

Is FSC letting forest destroyers off the hook?

FSC is currently trying out a new way to handle complaints, opting for mediation rather than investigation and punishment for offending companies, such as expulsion from the certification body. “We believe that should the complaint parties be willing to engage in a dialogue and remedy process then a successful resolution to the complaint is more likely,” FSC told Eco-Business.

Auriga said that changing the complaint handling mechanism will mean fewer complaints will lead to formal investigations, and in the case of the Djarum complaint, FSC is delaying investigating a case that may involve ongoing deforestation.

“If FSC does not have the capacity to carry out timely investigations of credible complaints, doesn’t that undermine the whole certification system?” said Syahrul Fitra, a researcher with Auriga.

“But our concern is even deeper than the temporary lack of capacity that FSC is claiming: does FSC leadership want to investigate complaints and enforce its own policies?” he said.

FSC’s decision to delay investigating Djarum Group came in the same month that the certifier denied a request for an update on a stakeholder consultation with FSC-certified palm oil and logging company Korindo.

A year ago, FSC said Korindo would be expelled from the certification body if the company did not commit to “social and environmental reparations and remedy” after an investigation exposed deforestation and human rights abuses in Papua.

After a request from NGO Mighty Earth for an update on the process, FSC said that, as a result of Covid-19, the organisation has undergone a “project prioritisation exercise” and would not look into the matter until the end of the year.

FSC said its dispute resolution team would be focused on select stakeholder engagement projects, such as reassociating with APRIL and Vietnam Rubber Group (VRG), a rubber company it is working towards bringing back into the fold. VRG was stripped of its certification in 2015 after an FSC investigation uncovered forest destruction and land grabbing.

Fitra said FSC risks losing its credibility and becoming like other certification schemes that are “strongly biased towards company interests.” FSC’s biggest rival scheme is the Geneva-based Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC).

“Forests, and everyone who depends on them, cannot afford to lose a strong-performing FSC, because the other options are woefully inadequate. So we earnestly plead with FSC to re-orient its decisions back to achieving its original mission of protecting forests.”

The Djarum and Korindo cases—which emerge amid reports that deforestation in Indonesia is accelerating during the Covid-19 outbreak—come after a report from a UK-based NGO alleged that FSC lapses had enabled furniture retailer IKEA to source illegal timber from forests in Ukraine.

Earthsight pointed at a conflict of interest in FSC’s audit process; much of its financing comes from companies that pay to have their supply chains certified.

FSC said that while the Earthsight report highlighted cases where its system had failed, it did not reflect the positive impact the organisation has had in holding rogue actors to account.