On Sunday 7 February, a sudden flood devastated a Himalayan valley in the Indian province of Uttarakhand. It tore through two hydroelectric dams, killing dozens of people and trapping hundreds more in construction tunnels.

With rescue efforts still underway, the disaster has swiftly become international news.

Media coverage has speculated about the cause of the devastation, with glacial lake “outbursts”, broken glaciers and avalanches all put forward as possible explanations.

In this factcheck, Carbon Brief unpacks how the events unfolded and speaks to scientists who suggest that a landslide was, in fact, the most likely primary cause.

And while further analysis is needed to assess the role of climate change, one scientist tells Carbon Brief that rising temperatures are causing “more of these big slope collapses”.

What happened?

According to police in Uttrakhand, the flood hit around 05:30GMT (11:00 local time). The torrent of water, ice and debris first destroyed the Rishiganga hydroelectric project – a small dam of roughly 13.2MW. BBC News reported that “the impact catapulted water along the Dhauliganga river” where it hit the much larger 520MW Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower construction project 5km downstream.

The floodwater was first noticed by residents of Raini village, which sits 3,700km above sea level, who filmed videos on their phones. The fast-flowing flood water swept away bridges, roads, homes and livestock, forcing officials to hurriedly evacuate villages along the banks of the Alaknanda and Dhauliganga rivers.

The district of Chamoli in Uttarakhand was hit hardest by the Dhauliganga flooding, with the village of Raini at the centre of the event. “It came very fast, there was no time to alert anyone,” Sanjay Singh Rana, who lives on the upper reaches of the river in Raini village, told Reuters: “I felt that even we would be swept away.”

The country’s disaster response team has been airlifted in, alongside hundreds of soldiers and members of the Indo-Tibetan border police. Two-and-a-half thousand people in 13 villages were cut off by the floods, but rescuers have now reached all 13 villages and relief work is underway.

When the flood hit, 35 people were working on the Rishiganga project and 176 people on the Tapovan Vishnugad project. According to the Guardian, 171 people have been reported missing and 26 dead – mainly construction and dam workers. According to a senior government official, many nearby residents work at the Dhauliganga plant, “but as it was a Sunday fewer people were at work than on a weekday,” the Associated Press reported.

Monday’s rescue operation focused on a 2.4km tunnel beneath the Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower dam, in which 39 workers were believed to be trapped. On Monday evening, at least 18 workers were rescued. Earlier, 12 workers who were building service tunnels were rescued from a smaller tunnel beneath the Tapovan-Vishnugad dam.

However, many more workers are still believed to be trapped in tunnels that have been blocked off with debris. Excavators are tunneling through the debris to reach them, but many are feared to be dead as no contact has yet been made with anyone in the tunnel.

Many outlets are concerned that this is reminiscent of floods in Uttarakhand in 2013, when several days of heavy rain washed away villages and killed almost 6,000 people.

What triggered the event?

In the immediate aftermath of the floods, initial reports suggested that a “glacial lake outburst flood” was a possible cause of the event.

Glacial lakes form behind natural dams created by debris collected at the front of glaciers and then left behind as glacier fronts retreat. As a Carbon Brief guest post from last year explained, thousands of such lakes around the world are expanding as glaciers melt in response to rising temperatures.

If the natural dam breaks, glacial lakes can cause potentially catastrophic outburst floods. According to one study, these floods have become “emblematic of a changing mountain cryosphere”.

The Indian Express, for example, reported that “scientists are not sure what triggered the sudden surge of water…[but] the scenario being most talked about was what glaciologists like to call a GLOF, or glacial lake outburst flood”.

In some cases, media reports suggested that a broken piece of a glacier could be a factor. CNN said “part of a Himalayan glacier fell into a river sending a devastating avalanche of water, dust and rocks down a mountain gorge, and crashing through a dam”. USA Today had a similar line in their reporting. While the Times of India reported that an “abrupt snowslide” could have been the cause.

(BBC News, Al Jazeera, CNN and USA Today all mentioned a “glacier burst” in their headlines, which one expert describes as “not a thing”.)

The remoteness of the area “means no-one has a definitive answer, so far”, said BBC World Service environment correspondent Navin Singh Khadka.

However, the Independent reported that “experts have also theorised that an initial landslide may have been the cause”.

This was supported by an American Geophysical Union (AGU) blog penned by the University of Sheffield’s Prof Dave Petley, which pieced together the weekend’s events with the help of other experts on Twitter.

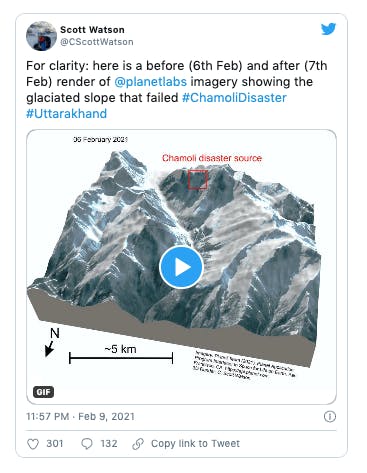

Using daily satellite imagery, Petley explained that a “block of rock, with some ice, dropped from about 5,600 metres to about 3,800 metres, a fall of almost two kilometres, before impacting on the valley floor”. This “will have instantly fragmented to generate a huge rock and ice avalanche, which travelled down the glacier. This would have been extremely fast and very energetic,” he added.

The gif below, which shows the before and after satellite imagery of the valley, highlights the section of rock and ice that fell.

india glacier

This rock avalanche “will have generated a huge amount of heat”, Petley continued, which will have incorporated glacier ice – “crushed and melted” – into the flow, creating a “debris flow”. He added that “the movement of the landslide was so rapid that the debris flow pushed water from the river ahead of it before incorporating it”. This can be seen in the clip below:

Prof Stephan Harrison – professor of climate and environmental change at the University of Exeter and lead author of the Carbon Brief guest post mentioned above – agrees that a landslide is probably the cause of the flood. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The most likely story so far is that a landslide impacted pre-existing avalanche snow and ice in the valley bottom, melted this – landslides generate a lot of frictional heat – and then this extra water and sediment increased the river flow.”

The “mobile debris flows” that this caused are unlike water floods, Harrison notes:

“They are extremely viscous and with long wavelengths so behave almost like a tsunami – which is why they are so destructive.”

Did climate change play a role?

In his blog, Petley describes the landslide as a result of “classic progressive failure in a mountain flank”. He explains to Carbon Brief:

“The archive satellite image clearly shows the development of fractures over the months leading up to the collapse. Initially, these formed at the upslope extent of the block that collapsed. Over the following months these extended down the flanks.”

This is a “signature” of a gradual weakening of the rock, Petley says, adding: “I cannot see how this can happen as a consequence of drilling or blasting.” Some reports had suggested that quarrying activity in the area – or even a fabled “long-lost radioactive device” – could have contributed to the disaster.

There is “no evidence on the [satellite] images of human interference”, Petley confirms, adding that “it is worth noting that the block was 1,800 metres up a near vertical rock face located above a glacier in very remote terrain”.

However, humans could have had an indirect influence on the event through warming caused by climate change, notes Petley:

“High mountain rocks are often heavily fractured. These fractures are filled with ice, which glues the rock mass together. Warming is causing this ice to deteriorate, which is weakening the rock masses. As a result, we are seeing more of these big slope collapses.”

This process is “well documented”, he adds. For example, a 2012 special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concludes:

“There is high confidence that changes in heatwaves, glacial retreat and/or permafrost degradation will affect high mountain phenomena, such as slope instabilities, movements of mass, and glacial lake outburst floods. There is also high confidence that changes in heavy precipitation will affect landslides in some regions.”

Rupert Stuart-Smith, a doctoral researcher at the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford, makes a similar point. He tells Carbon Brief:

“While further analysis is needed to fully evaluate the role of climate change in this event, previous research has shown that, as temperatures rise, the thawing of permafrost can decrease the stability of slopes and increase the probability of such landslides.”

(Last week, Stuart-Smith co-wrote a Carbon Brief guest post on his research attributing an expanding glacial lake in the Peruvian Andes to human-caused climate change.)

However, Harrison suggests that the thawing of permafrost – year-round frozen ground or rock – in steepened valleys sides is “unlikely” in this particular instance given that it is winter.

Another potential cause is a “seismic trigger”, adds Harrison, “but data here are rather scarce”. Ultimately, though, “what created the actual trigger may remain elusive”, he says.

Despite the uncertainty around the exact cause of the Uttarakhand landslide, Stuart-Smith warns that serious flood hazards will continue to develop as Himalayan glaciers “retreat rapidly”. He says:

“The formation of large glacial lakes in the wake of retreating glaciers threatens downstream communities with similarly devastating outburst floods in mountain regions around the world, including in the Himalayas of Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet. Unfortunately, growing numbers of these flood events are expected as temperatures rise and mountain glaciers recede.”

How has the media reacted?

In the days since the flood, newspapers in the region have commented on the impacts that development and climate change are having on the area.

An editorial in the Times of India warns that a “heavy duty infrastructural push in this ecologically sensitive region is taking place without rigorous enough local research”. It says:

“If mindless construction in an ecologically fragile ecosystem was considered a key contributor then, and continues to be a subject of much concern, the latest Himalayan tragedy is also a reminder of how close to home the frontier of climate change and global warming is.”“The danger here is that instead of mitigating the climate challenge, ill-conceived projects could end up multiplying the risks – and for all of India that lives downstream of the Himalayan rivers.”

The editorial says that the flooding was caused by “an extreme weather event”, but that damage was “compounded by unchecked construction on the riverbed”.

It also notes the “savage irony” that “the Chamoli village Raini that was in the centre of Sunday’s maelstrom was also the cradle of the Chipko movement in the 1970s.” A separate piece in the paper explains that the Chipko movement saw villagers in the Uttarakhand hills in the 1970s come together to save trees.

An editorial in the Tribune also notes the irony that Raini – “the cradle of the Chipko movement in the 1970s to save trees” – was the most severely impacted village.

The piece states that large hydropower projects are a divisive issue, adding that there is a “widening mismatch” between the need to preserve land and water resources, and the development plans put forward by governments.

The piece draws a clear link between the 2013 flash floods in Uttarakhand and the floods seen on Sunday, adding:

“If mindless construction in an ecologically fragile ecosystem was considered a key contributor then, and continues to be a subject of much concern, the latest Himalayan tragedy is also a reminder of how close to home the frontier of climate change and global warming is.”

On a similar note, an editorial in the Hindu calls the flood “a deadly reminder that this fragile, geologically dynamic region can never be taken for granted” and emphasises Uttarakhand’s “increasing fragility in the face of environmental shocks”.

It notes that “red flags have been raised repeatedly” in Uttarakhand, as many hydroelectric projects and dams have been planned and constructed with “little concern for earthquake risk”. Alarms were raised, in particular, after the moderate earthquake of 1991 in the area where the Tehri dam was later built, it notes as an example.

However, the paper recognises that India’s investment in dams and hydropower – especially in the Himalaya region – is important for its emission reduction targets. If India’s national plan to construct 28 river valley dams in the hills is recognised, India will have among the world’s highest densities of dams per square km, the article says.

The editorial concludes that it will be important to “rigorously study the impact of policy on the Himalayas and confine hydro projects to those with the least impact, while relying more on low impact run-of-the-river power projects that need no destructive large dams and reservoirs”.

An opinion piece in the Hindustan Times by journalist Chetan Chauhan also focuses on the residents of Raini, noting that, in May 2019, villagers petitioned against “illegal stone quarrying on the Rishi Ganga river bed, blasting of mountains and improper muck disposal by contractors engaged for construction of the Rishi Ganga hydel project”.

He says that the flood may “be nature’s way of telling humans that it can strike back when the ecological balance is destroyed”. Chahan argues that, while the exact cause of the flood is still unclear, there is “no doubt” that the impact would have been less if “more prudent developments projects” had been carried out in the region.

He also says that “the climate crisis may have aggravated the situation”, noting that, according to a recent report by the Kathmandu-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 36 per cent of glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region will be gone by 2100, even if the world sticks to it target of 1.5C warming.

Finally, an editorial in the Nepali Times says that the flood is “almost identical” to Nepal’s Seti River flash flood of 2012, which killed nearly 80 people. The article warns that “it is clear that the countries that share the Himalaya from Afghanistan to Burma have to be prepared for more frequent disasters of this type”.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.