The Philippines will have to spend billions of dollars in order to establish a nuclear facility that can safely manage radioactive waste and set up a national emergency plan in case of a disaster, according to watchdog Greenpeace.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Lawmakers have been trying to pass a bill to create an independent body to oversee the various uses of nuclear technologies in the country, but the proposed law does not provide any solution for such safety measures, said Greenpeace Philippines campaigner Khevin Yu in a press briefing on Friday.

In the event of a nuclear accident, up to US$588 billion will be needed by local government units across the Southeast Asian nation, based on the estimated cost needed to compensate victims and repair damages from the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan more than a decade ago, which killed over 2,000 residents, contaminated water sources and left nuclear fuel debris in communities, said Yu.

“[This] monstrous law will drain the country’s financial resources. We will need trillions of pesos to prepare for nuclear disasters as well as for waste storage and decommissioning. Energy consumers will pay for these costs in their electricity bills and shoulder the burden imposed by nuclear facilities,” he said.

As the domestic electricity sector is privatised according to the Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) law, it allows for generators and distributors to pass on costs to consumers.

The Bataan Nuclear Power Plant in the Philippines. The power plant cost over US$2.3 billion but never went into operation. Image: Jiru27, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikipedia Commons

Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos Jr met this month with United States-based nuclear energy firm NuScale Power Corporation to discuss a possible US$7 billion investment in small modular reactors (SMR), which may be installed in locations not suitable for larger nuclear power plants and have a lower emissions footprint than traditional facilities.

Marcos Jr has openly pushed for nuclear energy as a viable alternative to fossil fuels that could improve the country’s energy supply, which is vulnerable to seasonal outages. In his first state of the nation address, he highlighted the technology as a means to provide cheaper electricity in the country.

Even while campaigning for the presidency, he also spoke of revisiting the shelved Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP), which was built during the term of his father, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

The power plan, priced over US$2.3 billion, never went into operation. Constructed in 1976 in response to an energy crisis, and completed in 1984, the government suspended it two years later following Marcos’ ousting and the deadly Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine.

Nuclear power ‘can be cheaper’ in non-Western states

Contrary to the claims of nuclear proponents, the technology remains expensive globally, said Yu.

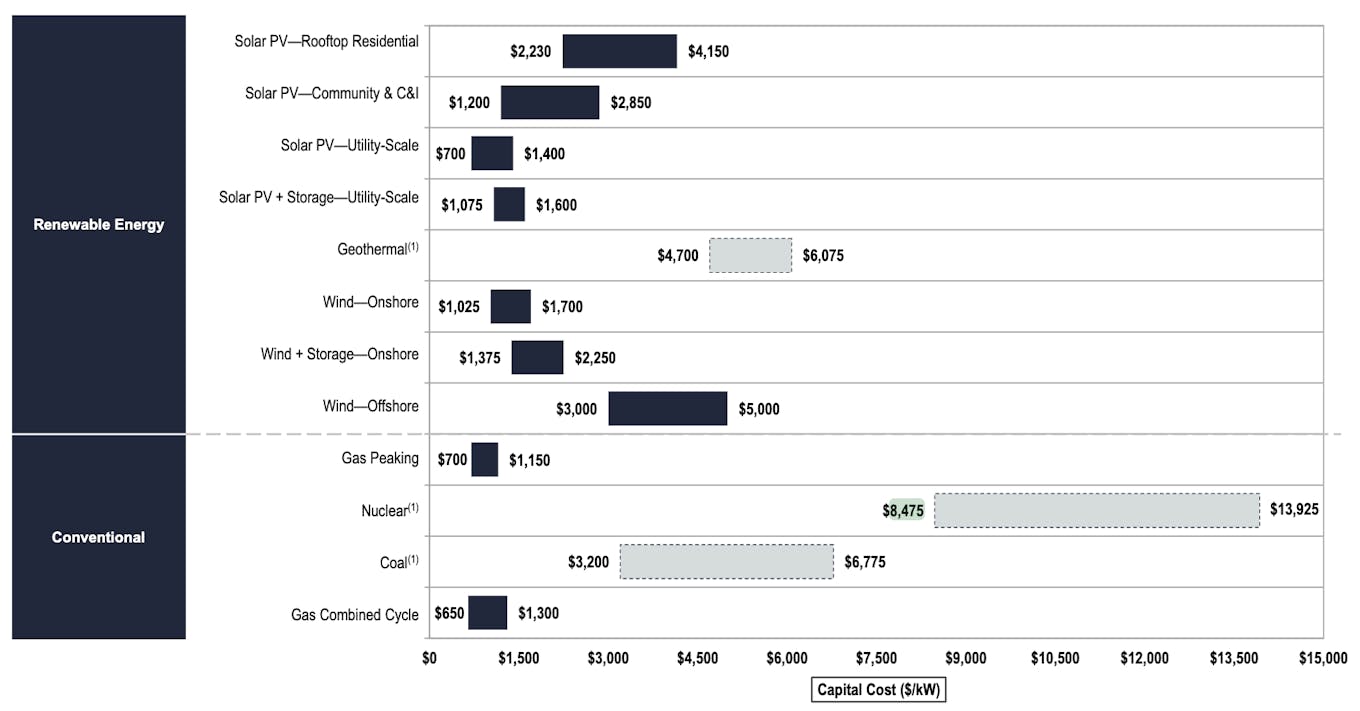

He cited a study by US-based investment bank Lazard which showed that the capital cost of a nuclear power plant can range from US$8,475 to US$13,925 per kilowatt hour (kW), compared to a coal facility which costs between US$3,200 to US$6,775/kW.

Meanwhile, solar power at utility scale is one of the cheapest energy sources at US$1,075 to US$1,600/kW, found the firm’s Levelized Cost of Energy report released in April.

Capital cost comparison among renewable and conventional energy. Image: Lazard

But the Lazard study only includes nuclear construction expenses of US-based facilities like the Vogtle Plant in Georgia, which requires more regulatory adjustments that cost time and money to comply with, noted Dr Carlo Arcilla, director of the Philippine Nuclear Research Institute, a government agency under the Department of Science and Technology.

However, the cost of nuclear plants in South Korea, China, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates are much lower because of weaker environmental regulations and less push-back from environmentalists, he said.

“Many environmentalists in the Western world make demands unrelated to safety but have significant cost implications when enacted. Examples of regulatory adjustmants are constructing an additional control room outside the nuclear plant, revising designs for interim waste disposal, among others,” he told Eco-Business.

Arcilla added that SMRs are also a cheaper alternative to conventional nuclear power plants, and will be able to address issues of waste, safety and construction time.

But once operational, smaller reactors cannot guarantee lower electricity costs: “There are [still] no operating SMRs as compared to more than 430 traditional nuclear power plants that exist. Within 10 years they will come but will have to be vetted operationally,” he said earlier this month.

The only operating SMR facility in Russia was built on the basis of an already existing design of a nuclear submarine reactor, was not modular, and still took over a decade to finish. There are currently four SMRs in advanced stages of construction in Argentina, China and Russia, and several countries are conducting SMR research and development.

Want more Philippines ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Philippines newsletter here.