What are green bonds?

Green bonds are used by governments, banks, municipalities or corporations to raise cash for new or existing projects that are meant to have positive environmental and climate impacts. Bonds can cover energy, water management, building construction, water, land use and transport.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Projects might be specifically aimed at energy efficiency, pollution prevention, sustainable agriculture, fishery and forestry, the protection of aquatic ecosystems, clean transportation and sustainable water management.

Some economists speculate the potential for issuances related to hydrogen or carbon capture, utilisation or storage, as well as new technologies that will increase emission efficiency in a broader range of industrial processes.

Trillions of dollars are needed to meet ambitious zero-emissions goals. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated in 2019 that $1.5 trillion of annual investment is required for Asia to meet its demand for infrastructure which will rise to $1.7 trillion per year for sustainable, resilient infrastructure that is required to mitigate the impacts of climate change such as rising sea-levels and the increase in severe weather events. Green bonds will help bridge the finance gaps that cannot be covered by the public purse.

How fast are green bonds growing?

The market opened slowly more than a decade ago but investor demand for sustainable investment options, given the rising emphasis on meeting zero-emissions targets, is driving growth.

Green bonds still only represent a sliver of the total $100 trillion global bond market, but issuance reached a record high of $269.5 billion by the end of last year and could reach $400-$450 billion this year, according to a recent report by Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), a non-profit.

Green bond sales in Asia lagged the rest of the world in 2020. But Asia’s green financing will see a boost this year to help meet China’s President Xi Jinping’s ambitious environmental goals amid uneven economic recovery post-Covid.

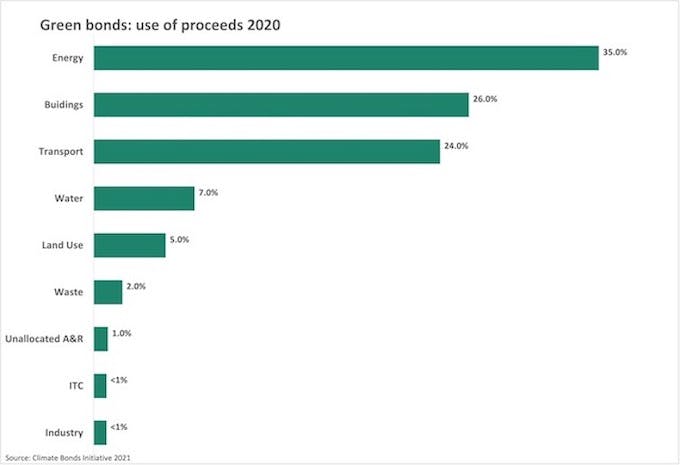

Investment in the energy sector comprised the largest share of 2020 issuance, at $93.6bn. Low carbon buildings came in second at $70 billion followed by low carbon transport initiatives at $63.7 billion.

What makes a green bond green?

Here is the catch. There is currently no official overarching regulation that defines a green bond and the principles that do exist are voluntary rather than legally binding.

In practice, many issuers tend to follow the Green Bond Principles (GBP) endorsed by the International Capital Market Association. These are voluntary principles and guidelines that define eligible use and management of proceeds, the evaluation process for projects and the reporting to investors.

Otherwise, a wealth of companies offers independent assessments to rubberstamp a bond’s green credentials including the CBI and CICERO Shades of Green. The Nordic Public Sector Issuers has also produced a paper on impact reporting.

A major development in setting official standards for green bonds is the proposed European Union Green Bond Standard which should make it easier for investors to identify sustainable investments and ensure that they are credible. The proposed EU taxonomy includes a detailed criterion for green projects and encourages the supervision of third-party reviewers.

China is working with its European counterparts on the framework as it looks to raise hundreds of trillions of yuan to help it achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. However, debates around what ‘qualifies’ as green could derail the progress of the EU taxonomy.

How green are green bonds?

It depends. An issuer of green bonds does not have to be the purest shade of green — “a fact possibly underappreciated by investors,” said a study by Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a group of central banks. Even if the proceeds are channelled into green projects, “issuers may be (and often are) heavily engaged in carbon-intensive activities elsewhere,” the study found.

Some might then wonder how credible a green bond is from an issuer that is not green across its business. China, the world’s biggest carbon emitter, is the second most prolific green-bond issuer. It uses green bond investments to support a considerable number of oil and gas-related projects as well as large-scale hydropower. Nevertheless, China axed its ‘clean coal’ from its green bond catalogue last year to bring it closer in-line with international standards.

The issuance of green bonds for clean coal was highly controversial, but also pointed to a deeper mismatch between China’s definition of green and that of Western investors. Change will be gradual, economists say. “There is greater demand from some investors — mainly in Europe and the U.S — that those who are issuing bonds are not doing harm,” Sean Kidney, chief executive of the Climate Bond Initiative, told Eco-Business.

Are they having impact?

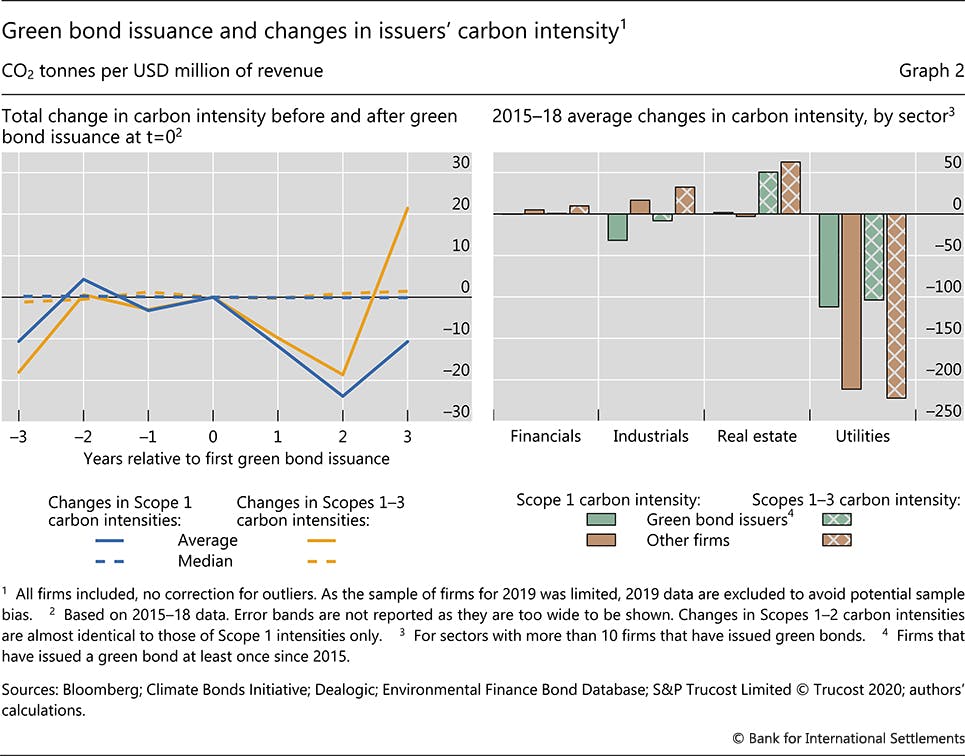

It is a mixed bag. Green bonds issuance does not lead to falling or even comparatively lower carbon emissions by the firms selling them, according to the BIS report.

Researchers looked at around 200 large firms that issued green bonds in 2015-18, and concluded that firms that issue the most tend to be cleaner to begin with, producing less carbon for a given amount of revenue.

The research also found that green-bond issuance did not seem to lead to decarbonisation. “Green bond labels are not associated with falling or even comparatively low carbon emissions at the firm level,” the report said. Its statistics (see chart below) showed the average carbon intensity varies but there are not significant changes.

Green-bond issuance did not seem to lead to decarbonisation, according to a study by the Bank for International Settlements.

Green bonds are no silver bullet, but that does not mean they will not drive positive action within companies and governments, charges Kidney of CBI. “You really have to get governments and then other institutions to shift their strategies to low carbon and climate resilience in everything from energy policy to capex policy. Green bonds are an ice breaker for that kind of activity,” he told Eco-Business.

What is the point then?

Reputation. Companies gain a virtuous advantage from issuing green bonds. They can create a lot of publicity driving up share prices. There is also additional pressure on companies to push down their carbon output as part of a wider effort to comply with country commitments to zero 2050 targets. Green bond issuance can satisfy investors who are being pressed by their clients to brush-up their green credentials.

“There’s a climate policy risk filter now being applied to the economy, which wasn’t being applied before, which is why investors are asking for commitment,” said Kidney. “They are looking for companies that will keep ahead of the wave of policy change coming through.”

Are green bonds the same as sustainable bonds?

No. Sustainability-linked bonds are a relatively new type of debt hinged on companies pledging to do good and agreeing to pay penalties if they fail to fulfil their promises. Unlike green bonds, they are not earmarked for one project. Instead, loans can be linked to specific environmental, social or governance targets giving companies an incentive to hit targets and be rewarded financially.

There are also “transition” bonds providing big polluters the fundraising opportunity to reduce their environmental impact.