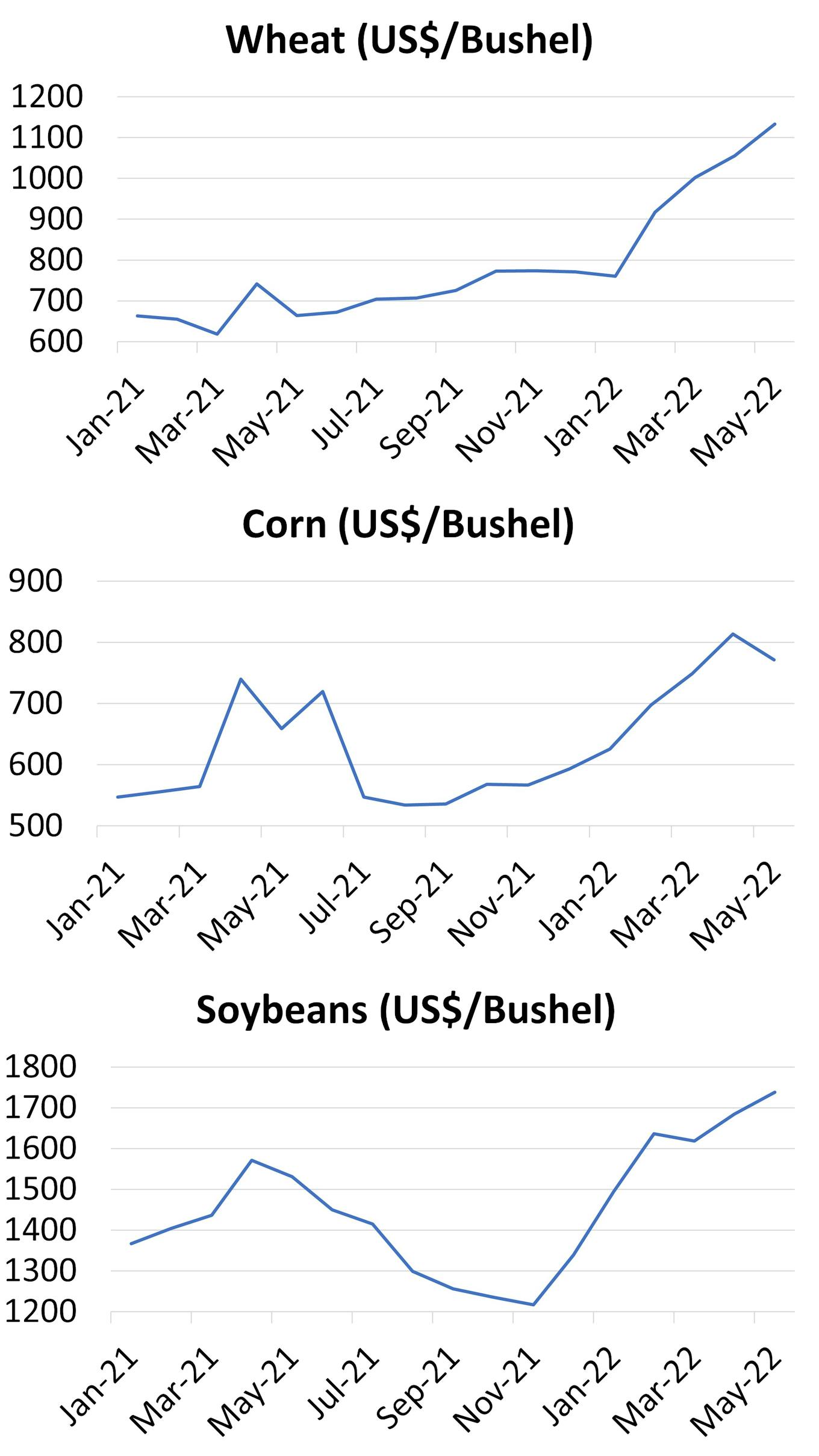

First went wheat and corn, when Russia invaded Ukraine in February, resulting in beseiged ports and trade embargoes. The two countries exported a quarter of the world’s wheat and a sixth of the world’s corn before they went to war.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In May, India joined the fray, banning wheat exports as a massive heatwave singed crops, threatening local supply. Harvests in several parts of Africa, Australia and Europe were also battered by droughts and floods.

Indonesia banned palm oil exports for nearly four weeks in April and May as prices soared, pushed up by the shortage of sunflower oil from Ukraine. Palm oil is the world’s cheapest and most widely used cooking oil, and Indonesia is its largest producer.

Come June, Malaysia will ban the export of all but the most expensive chicken varieties, in a bid to tame runaway prices. The ban rounds off trade restrictions in all three macronutrients – carbohydrates, fats and proteins – that humans need to survive.

“They are not separate, you have to look at them as integral parts,” said Professor William Chen, director of the Food Science and Technology Programme at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

Prices of key grain commodities. Data: Trading Economics. [click to enlarge]

“When you have a shortage in wheat, it will push up the price of wheat, which pushes up the price of animal feed. As a result, chicken farmers will suffer,” Chen said.

The main ingredients in chicken feed are soy and corn – highly traded commodities whose prices rise and fall on a global scale, regardless of where the crops come from.

“Farmers can’t break even, some are suffering losses,” said James Sim, head of business development at Kee Song Food Corporation, which runs 17 chicken farms across Malaysia.

Shoppers in neighbouring Singapore, which sources a third of its chicken from Malaysia, cleared supermarket shelves of chicken in anticipation of shortages. Sim said he has received orders from Singapore 10 times higher than usual ahead of the export ban, which he is unable to fulfil.

As the world headed into 2022 hoping to have recovered from the Covid-19 pandemic, conflict and climate change have dealt a sucker punch to the world’s food supply. Shortages and skyrocketing prices threaten to burn holes in the pockets of the middle class, and starve the poor.

It has also amplified the debate around fixing the global food system, which experts fear may crack under the weight of continued population growth, climate change and the degradation of fertile soils.

Malaysia’s chicken export ban highlights the world’s overproduction of meat, said Chen. Currently, about 20 per cent of harvested crops are used to feed animals, from which eggs, milk and meat are derived. In Europe, the proportion goes up to 62 per cent.

Globally, close to 80 per cent of farmland is used for rearing livestock, including plots for grazing and growing feed crops.

Experts have argued that it is more efficient to grow crops for direct human consumption. Such crops, planted on just 20 per cent of agricultural land, already contribute to over 80 per cent of the world’s calorie intake. Poorer countries also tend to rely more on plant crops.

Empty shelves at the poultry section of a supermarket in Singapore. Image: Liang Lei/Eco-Business.

“The chicken ban is just the tip of the iceberg. The other types of meat industries will also be affected,” Chen said. Corn, wheat and rice are key parts of pig and cattle feed, and prices for beef and pork cuts have started creeping up. Soy is also used in some types of fish food.

As it stands, disruptions in the meat industry have not been as considerable as those in grains and edible oils. Argentina, the world’s fifth largest beef exporter, has a partial ban in place to control prices. Smaller players Turkey and Kyrgyzstan also have beef export restrictions in place, but similar to Malaysia’s chicken ban, are unlikely to cause a huge global shortage.

Nonetheless, Chen believes it is time to start shifting away from intensive meat production.

“If we don’t start changing our practices, and taking a proactive approach, then consumers will always be on the losing end,” he said, adding that solutions could include plant-based proteins. According to lobby group Good Food Institute, plant-based options are still up to twice the cost of animal-based products today, but price parity could be reached this decade.

“

The food crisis now is the realisation that chemical-based intensive monoculture cannot sustain food production.

Ng Huiying, doctoral researcher, anthropology, Rachel Carson Center

Boosting yields amid climate change

Regenerative agriculture had multiple moments in the limelight at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland last week, with several farming multinationals bringing up the term in panel discussions.

“Food companies are increasingly talking about it, governments are increasingly talking about it. Banks too,” said Erik Fyrwald, chief executive of Syngenta, an agrochemicals company.

“It has to be deployed over many more acres, for many more crops, and in many more regions,” added Hanneke Faber, president of the foods and refreshment division of consumer goods firm Unilever.

Regenerative agriculture centres on improving soil and ecosystem health in farmlands, with techniques such as growing cover crops in winter to keep carbon in the soil and composting agricultural waste and planting native trees. In theory, these practices could benefit both crop yield and the environment.

Such techniques could be one of the most effective climate mitigation strategies of the decade, according to the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a network of scientists under the United Nations (UN). In turn, with lower emissions and temperature rise, agriculture could be spared from extreme floods and droughts.

There are willing supporters too.

“We want to position ourselves, in the African continent, as being one of the places you can try these innovations,” said Clare Akamanzi, chief executive of the Rwanda Development Board.

Still, there are reservations about how large firms are wielding the term “regenerative agriculture”, possibly for corporate gain. Key issues include the lack of a consistent, formal definition, opening the doors to greenwashing.

But with the world population set to increase to 9 billion by 2050, and researchers estimating that food production will need to increase by 50 per cent, some form of scaling up may be inevitable, especially in Asia – both one of the fastest growing regions, and a net food importer.

“To be more food secure in Asia, one solution is to tackle the smallholder farmer issue – a lot of them in Asia, with less than half a hectare of land, need to rise above subsistence farming to become commercial farmers and make a profit out of farming,” said Professor Paul Teng, a researcher on food security at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

“The way to do that is through technology, whether it is better seeds, the use of fertilisers, or better waste management – the three big things, along with better management of pests and diseases,” Teng added.

Organic farming has also been the subject of recent debate. Fyrwald of Syngenta said abolishing the use of chemical fertilisers could cause more hunger with lower yields, as well as higher soil carbon emissions, in an interview with Swiss publication NZZ am Sonntag.

His comments attracted pushback from environmental groups, which labelled his comments “fake news”.

The episode comes on the back of a disastrous attempt to switch an entire nation to organic farming in Sri Lanka, which is leading to what could be a 50 per cent fall in production this year. Observers say the government’s blanket ban on synthetic fertilisers and lack of planning were central to the looming food crisis.

Current research suggests that organic farming could result in lower yield in the short run, but could catch up with conventional practices after 10 to 13 years, while ensuring better soil structure and less nutrient leaching.

More funding has gone into organic farming, but the focus has been on large projects, according to Ng Huiying, a doctoral researcher in anthropology at the Rachel Carson Center.

Local knowledge and practices in non-chemical farming should be prioritised over organic farming certifications that could be costly and often come with a multi-year transition period that smaller farms struggle with, Ng added.

“There are so many ways of doing this in different countries, in different languages,” said Ng.

“The food crisis now is the realisation that chemical-based intensive monoculture cannot sustain food production,” Ng added.

“It’s almost like chemical warfare on the land,” she said.

Trading food better

Reducing the distance from farm to table could help improve food security too, according to Ng.

Shorter supply chains, such as those linking rural areas to cities in the same region, have been found to work in places like Thailand, where villagers provided food to the poor in Chiang Mai city during Covid-19 lockdowns.

“For countries that have been used to importing food for a long time, this means expanding our understanding of what we can source from nearby, and how we can support workers nearby,” she said.

Ng added that the current food system that prioritises cash crops and global trade results in unjust outcomes, pointing to how Africa today is a net food importer. Export-oriented farm systems in Africa’s colonial era have been cited in studies as a reason for its dependence on imports and food aid today.

“It’s not because of climate change that they couldn’t grow food,” Ng said, referring to a speech that Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, had made at Davos.

“Climate change made water scarce, and the desert swallowed hundreds of kilometers of fertile land, year after year. Africa is now heavily dependent on food imports and this makes it vulnerable,” Von der Leyen said.

“

We are in a moment where we need a shift. We need to rethink the way we produce, and the way we consume.

Ibrahim Thiaw, undersecretary-general of the United Nations

Attendees at Davos maintain that global trade is key to solving the food crisis.

“It is incredibly important that we have a predictable trade regime and that we incentivise trade, because we know that trade is the engine behind much of the growth that we have seen in the past three decades,” said Svein Tore Holsether, chief executive of agrochemicals giant Yara International.

Eschewing protectionism in the short-term will be key to alleviating food shortages, said Teng.

“Exporters should not in any way keep back exports, because globally, there is the phenomenon where if any country decides to hoard, that sets up a chain reaction. As we’ve seen, once the chain reaction starts, it is really difficult to stop,” he said.

That, along with an end to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, could provide relief for the 325 million people who are close to starvation today. But relieving them from hunger down the road could require more changes to the global food system.

“We are in a moment where we need a shift. We need to rethink the way we produce, and the way we consume,” said Ibrahim Thiaw, undersecretary-general of the UN.