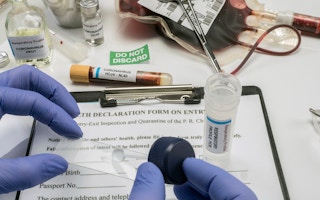

Around the world, countries and individuals are isolating themselves to try to stem the spread of Covid-19. But to find a solution to the crisis - particularly a vaccine - global cooperation will be crucial, say a growing number of leaders.

“We will not be able to get out of this health crisis by simply boarding ourselves in,” former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres told an online event this week.

Creating, distributing and administering an affordable, accessible vaccine will take a coordinated international effort - similar to that needed to tackle climate change, she said.

“As long as there is one person carrying the virus, everyone is under threat,” she warned.

On Thursday, about 140 public figures, including the leaders of three African nations and Pakistan, called on governments and their international partners to guarantee that, when a Covid-19 vaccine is developed, it is produced rapidly at scale and made available for all people, in all countries, free of charge.

Figueres, one of the signatories of the open letter for a “people’s vaccine”, said working together to find a solution to the pandemic was an opportunity “to exercise the muscle of international cooperation which is critical for climate change”.

As trillions of dollars in stimulus spending begin pouring into national economies flattened by the coronavirus crisis - and as people rethink old habits - the world faces a rare opportunity to swiftly ramp up climate action, Figueres said.

About $20 trillion in global stimulus spending is likely to be deployed, the Costa Rican diplomat said - in the same decade scientists say is crucial to pushing rapid change to avoid the worst consequences of global warming.

Decisions about how that money is spent will likely determine whether the world succeeds - or fails - at stopping runaway climate change, said Chris Stark, chief executive of the UK Committee on Climate Change, which advises the government.

“Do we turn away conclusively now from fossil fuels and lock in a genuinely low-carbon future? Or do we repeat the mistakes of the last recession?” he asked in a separate online event on Thursday.

If money again goes to prop up fossil-fuel-based industries, “the goals of the Paris Agreement are going to be very difficult” to meet, he said.

“

We haven’t decarbonised the economy, we’ve only paralysed the economy. As soon as we get the wheels going again, those emissions will go up.

Christiana Figueres, former executive secretary, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Lower emissions?

Global emissions of climate-changing gases are expected to drop 8 per cent this year, according to the International Energy Agency.

That is a touch more than the 7.6 per cent drop scientists say is needed each year this decade to meet the Paris accord goal of holding global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times.

“But the drop this year should not be a matter for celebration,” Figueres noted. “We haven’t decarbonised the economy, we’ve only paralysed the economy. As soon as we get the wheels going again, those emissions will go up.”

Raffaele Mauro Petriccione, climate action director-general for the European Commission, said he agreed that “all focus will be on repairing our economy and restarting it and trying to avoid economic damage” once the virus threat lifts.

Meanwhile, rising climate pressures “will not go away when we have found a solution to this (virus) crisis. And if we have lost time (in dealing with them)… that is not time we can make up,” he said.

Still, some climate-friendly changes seen during the pandemic may stick, Figueres said, from a reduction in air travel, particularly for business, to continued working from home, which cuts emissions from commuting.

“So many people are realising we can be just as effective, or almost as effective, from home. You don’t have to put up with the lengthy commute - and corporations will realise they can also save money on office space,” Figueres said.

To hold onto and encourage such shifts, governments will have to put in place the right policies, such as investing in broadband instead of more roads, Stark said.

Putting money into retrofitting old homes - a big contributor to emissions - also could make sense, along with quickly phasing out combustion engines, said Nigel Topping, a UK champion for the now-delayed COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

Sam Greene, a climate change researcher with the London-based International Institute for Environment and Development, said broad new recognition of how vulnerable people and systems are to unexpected threats could help drive appetite for change.

“There’s an opportunity here not to talk about what we have to have less of (to deal with climate change) but how we can create a more just and resilient future,” he said.

This story was published with permission from Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, climate change, resilience, women’s rights, trafficking and property rights. Visit http://news.trust.org/climate.