Animal-sourced products and their global supply chain are a significant contributor to global land-use change and the greenhouse gas emissions they cause.

The study, published in Nature Communications, uses a global economic model for land use to assess the food system-wide impacts of a global dietary shift towards plant-based alternatives, such as soy protein and vital wheat gluten.

The researchers find that a global switch from a meat- and dairy-heavy diet for plant-based alternatives could cut greenhouse gas emissions associated with agriculture and land-use change by 31 per cent.

The wider environmental benefits of such a shift would vary around the world due to differences in population size, diets, agricultural production and export levels, the study says. China, for example, would see the largest reductions in fertiliser use, water use and emissions from agricultural land use, while sub-Saharan Africa and South America would have the largest share of restored land and subsequent carbon sequestration.

The researchers argue that such a change in global consumption could contribute to fulfilling international agreements, such as the global land restoration target established by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

New plant-based alternatives

The global production of animal-sourced foods, such as meat and milk, requires the use of a wide range of resources, including land, water and energy.

As a result, animal-sourced foods are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions and harm to global biodiversity. Scientific evidence also says the overconsumption of these products, especially red meat and processed meats, can affect human health.

New plant-based alternatives for meat and milk have emerged as another option. The term refers to food made from plants or fungi that mimics the taste and consistency of animal products, such as soy protein, wheat gluten and oat and almond milk.

According to the study, these alternatives are gaining popularity in parts of the world. In the US, for example, they represent 15 per cent of the milk market.

Environmental benefits

The study assesses the environmental, economic and nutritional impacts of a global substitution of the leading animal-sourced foods – pork, chicken, beef and milk – with plant-based alternatives.

The researchers created hypothetical plant-based recipes, using ingredients such as soy and potato protein, peanut flour, cassava and beans, that had similar nutrient profiles to those in their animal-derived counterparts.

“

There are ways to ensure both benefits: that the farmers have an income, but also that the land is used in a way that is serving the environment. So, basically, that is a forest [used] in a sustainable way, that is also good for biodiversity.

Dr Marta Kozicka, researcher, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

The research models five scenarios of dietary changes under the SSP2 shared socioeconomic pathway, a future scenario where economical and technological trends broadly follow historical patterns. In a reference scenario, the researchers assume that changes in animal-sourced food consumption patterns follow economic growth. In the others, they consider the replacement of meat and milk by alternative plant-based foods in varying proportions ranging from 10-90 per cent.

The authors then analyse the scenarios through an economic model that integrates land-use information, such as agriculture, bioenergy and forestry. Finally, they explore the impacts of dietary changes through various indicators, ranging from greenhouse gas emissions, land-use change and biodiversity to crop prices and food security.

In the reference scenario, the researchers observe increased overall global food demand and average per-capita consumption of all main animal-derived products, especially chicken and milk. The demand for crops grows and prices decrease, which results in increased food security.

However, this scenario “exerts further pressure on natural resources” as compared to a 2020 baseline, according to the study. For example, agricultural expansion clears about 255m hectares of forests and natural land; nitrogen use grows by 39 per cent and water use by 6 per cent; greenhouse gas emissions increase by 15 per cent; and biodiversity declines by 2 per cent.

In the plant-based alternatives scenario, there is reduced crop demand. Each substitution scenario shows price reductions for both crops and animal-sourced foods and improved food security. At higher substitution rates, the researchers include more recipes for the alternative products.

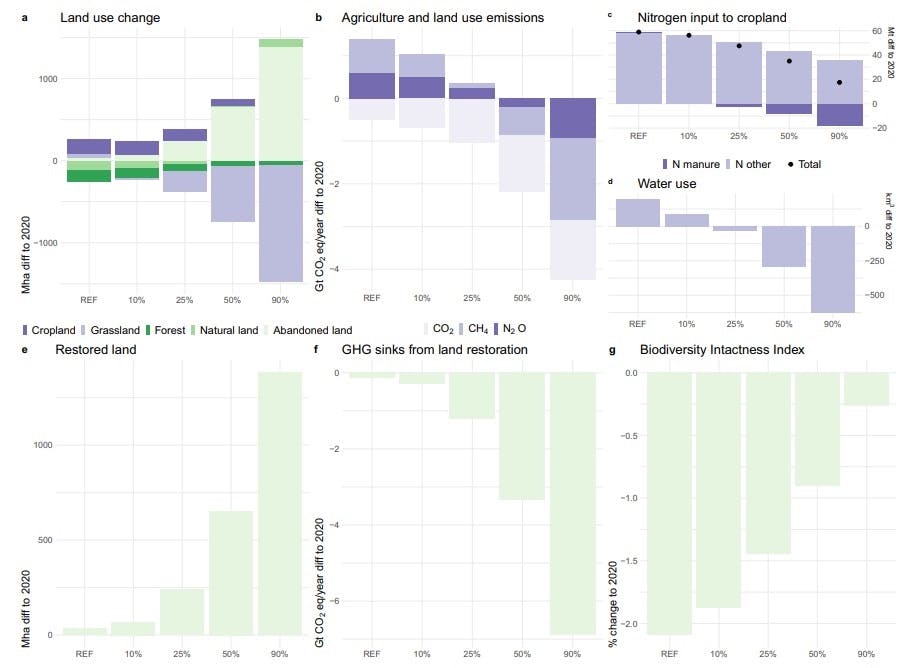

The charts in the upper section of the figure below represent the global impacts of substituting animal-sourced foods for meat-free alternatives by 2050 on land-use change, agriculture and land-use emissions, and nitrogen fertiliser and water use.

The lower section shows the amount of land restored, the potential carbon sink of this land and the changes in biodiversity under each scenario.

For the land-use change chart, dark and light purple represent cropland and grassland, respectively, while dark, medium and light green represent forest, natural land and abandoned land. For the associated emissions chart, the light, medium and dark purple each represent a different greenhouse gas: CO2, methane and nitrous oxide. For the nitrogen input chart, dark purple is the amount of nitrogen applied as manure, and light purple is the nitrogen applied in other forms.

Global environmental impacts of substituting meat and milk for novel alternatives, across five scenarios (left to right): reference scenario (consumption of meat and milk in line with historical trends) and substitution by plant-based products of 10 per cent, 25 per cent, 50 per cent and 90 per cent. The top charts depict the results of the dietary change alone on (a) land-use change, (b) emissions from agriculture and land use, (c) nitrogen fertiliser use and (d) water use. The bottom charts show the additional impacts of land restoration on abandoned agricultural lands on (e) the amount of land restored, (f) the carbon sink of those lands and (g) the biodiversity of those lands. Source: Kozicka et al. (2023)

The study finds that with 50 per cent of animal products substituted for more sustainable alternatives, “all impacts on natural resources decline significantly” by 2050. Global agricultural area decreases by 12 per cent, which releases 653m of hectares of land for other uses. Nitrogen use is halved, compared to the reference scenario. Water use drops 10 per cent and greenhouse gas emissions decrease by 2.1bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent (GtCO2e) per year by 2050.

The research also finds that in a 50 per cent substitution scenario, if governments implement additional measures to restore the abandoned croplands, such as tree-planting and biodiversity-friendly management, carbon sequestration would rise by an additional 3.3bn tonnes of CO2e per year by mid-century.

In the 50 per cent scenario, the restored area would meet nearly 13-25 per cent of the land restoration needs set out in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and 58 per cent of the Bonn Challenge targets, which aims to restore 350m hectares of degraded and deforested areas by 2030.

According to the study, this is the first time a comprehensive analysis of a global dietary change considering novel plant-based alternatives has been carried out. It points out that other studies have had limitations in their scale and scope or the range of impacts and potential market developments.

Prof Barbara Vizmanos, research coordinator of the University Centre for Health Science at the University of Guadalajara, who was not involved in the study, agrees with that assessment. She tells Carbon Brief:

“[The study puts forward] a valuable proposal of analysis that allows us to imagine a range of possibilities for making decisions, both as countries (establishing policies, education [and other measures]), but also as subjects [deciding what to eat]”

Land-use change

According to the study, beef substitution holds the biggest potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and impacts on land use and biodiversity. It also notes that all substitutions together have a greater impact than an individual substitution.

However, such a dietary shift might occur at a different pace in different parts of the world. The researchers consider 13 countries and regions and examine the model output for each individually.

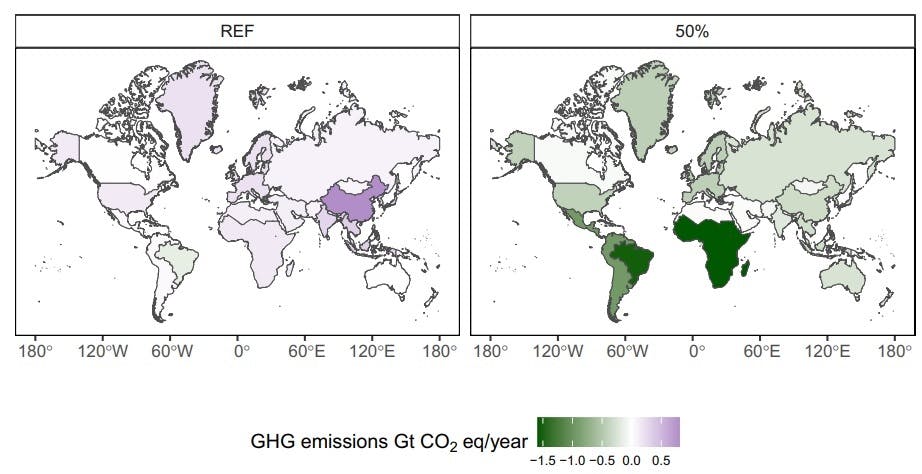

In the 50 per cent substitution scenario, for example, China would account for 25 per cent of the global cropland abandonment and 22 per cent of agricultural emissions reduction. Sub-Saharan Africa would hold 37 per cent of the potential to reduce natural land loss and 47 per cent to reduce land-use change emissions. This region, along with Brazil and other South American countries, could have the largest share of restored land and carbon sequestration.

The maps below illustrate the emissions change from the agricultural and land use sector by region from 2020 to 2050, in both the reference (left) and 50 per cent substitution (right) scenarios. In the maps, purple indicates an increase in annual CO2e emissions, while green indicates a decrease. The darker the colour, the stronger the effect.

Emissions change from the agricultural and land use sectors, divided by region, from 2020 to 2050 under the reference scenario (left) and the 50 per cent substitution scenario (right). Colours indicate the strength of the changes in emissions, with darker purple (green) representing higher (lower) emissions. Source: Kozicka et al. (2023)

Lead author Dr Marta Kozicka, a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, says that the global south could benefit the most from transitioning towards novel plant-based alternatives, such as less loss of forest land and biodiversity. She adds that further policies would need to consider ensuring farmers’ livelihoods.

For example, for farmers moving away from livestock production, one option is to implement ecosystem service payments, where farmers are paid for more sustainable farming or for not converting their lands to monocultures. Kozicka tells Carbon Brief:

“There are ways to ensure both benefits: that the farmers have an income, but also that the land is used in a way that is serving the environment. So, basically, that is a forest [used] in a sustainable way, that is also good for biodiversity.”

Enabling a dietary change

Vizmanos tells Carbon Brief that meat and milk alternatives “do not, by themselves, pose any health risk”. She continues:

“Obviously, it will depend on the type of processing and the quality of the ingredients used at the base, as well as ensuring a varied consumption of vegetables, in order to ensure that the dietary requirements are met.”

Substituting 10 or 25 per cent of animal-based foods for plant-based alternatives would not trigger any concerns over possible micronutrient deficiencies, Vizmanos says. However, if the world were to reach the 50 per cent substitution presented in the study, people would be at risk of similar micronutrient deficiencies that vegetarians often face.

Vizmanos notes that some key nutrients for people on vegetarian diets include omega-3 fatty acids, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, vitamin D and vitamin B12. Proposals for expanding alternative plant-based foods should consider all of these micronutrient needs, she argues.

Raychel Santo, a food and climate research associate at the World Resources Institute thinktank, has a different perspective. She tells Carbon Brief:

“For most measures, plant-based meat alternatives have a better nutritional profile than the meats they are intended to replace, with less fat, saturated fat and cholesterol, more fibre and similar amounts of protein.”

She notes the need for more research examining the long-term impacts of novel alternatives for meat and milk on health, such as the risks of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and some types of cancer.

For people reluctant to try novel plant-based alternatives, there are other options, including balancing their diets with more vegetables and legumes to meet their nutritional needs or even consuming insect-based alternatives, suggests Kozicka.

Santo agrees that consuming legumes such as beans and lentils has health and environmental benefits and would be cheaper than the novel alternatives. More research is needed to make plant-based meats and milks match the taste, texture and price of animal products, she says, adding:

“The value of meat alternatives is that they can provide a similar experience to consumers who want to eat meat with fewer public health, environmental and animal welfare harms.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.