From the top of a rickety fire tower overlooking a palm oil estate in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, the damage caused by the devastating fires of 2015 still makes for a sobering sight 18 months on.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

What remains of pristine forest are the skeletons of trees, morbidly known as a “forest cemetery”, standing awkwardly on a thin covering of ferns and mosses. What was a charred war zone is finally showing signs of life.

The fires, which contributed to the worst haze air-pollution crisis ever seen in Southeast Asia, devoured 2,000 hectares of carbon-rich peatland set aside for conservation by PT Agro Lestari Mandiri (PT AMNL), a palm oil company owned by Golden Agri Resources (GAR), the world’s second largest oil palm producer.

The El Niño weather phenomenon had meant that the monsoon rains came late, and the fires - which observers said were started deliberately to clear land for agriculture - raged on for three months, the flammable peat soil burning deeply underground.

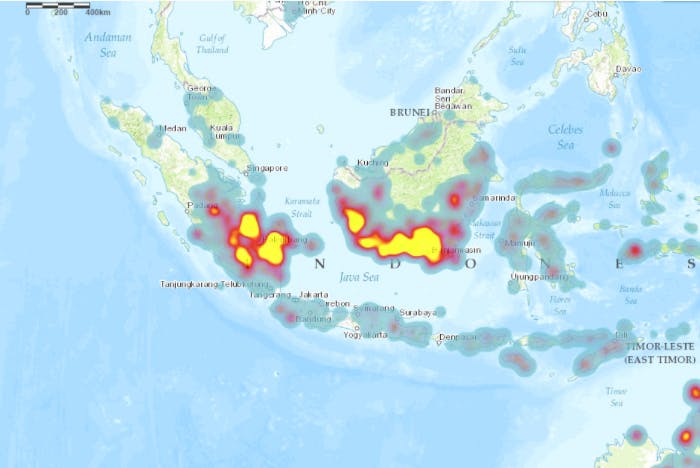

This map, drafted by forest monitoring group Global Forest Watch, shows the height of the land burning activity in September 2015. Kalimantan is right at the centre of this map.

Active fires in September 2015, the height of Indonesia’s record-breaking year for the haze. Image: Global Forest Watch

According to the Indonesian government, the fires were responsible for US$16 billion in economic losses - almost as much as the palm oil industry’s contribution to Indonesia’s GDP in 2016 (US$17 billion).

A study by Harvard and Columbia universities found that the haze, which was called a “crime against humanity” by the head of Indonesia’s meterology agency, killed 100,300 people prematurely in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, but this statistic has been refuted by the governments of these countries.

There has been little accountability for the fires. Though there have been some arrests made and trials are ongoing, Indonesian police recently threw out a case to prosecute 15 companies linked to the haze, even though the law states that firms will be punished for failing to prevent fires in their concessions.

Smallholder farmers tend to get the blame for the fires, although some burn the land to sell it on to big oil palm companies. The trade in burned land is known as terima abu, or receiving the ashes, which fertilise the soil.

According to a recent study by Singapore’s NUS Business School, peat forest fires and the resulting haze pollution have been linked to the increase in the stock prices of palm oil firms; investors see the fires as an indication of a healthy, expanding palm oil sector.

Burning is the quickest and cheapest way to clear land, and is a traditional method that has been used in Kalimantan and Sumatra for generations. Clearing land with fire costs around US$5 per hectare, while using machines and chemicals costs 40 times as much.

The fires go out

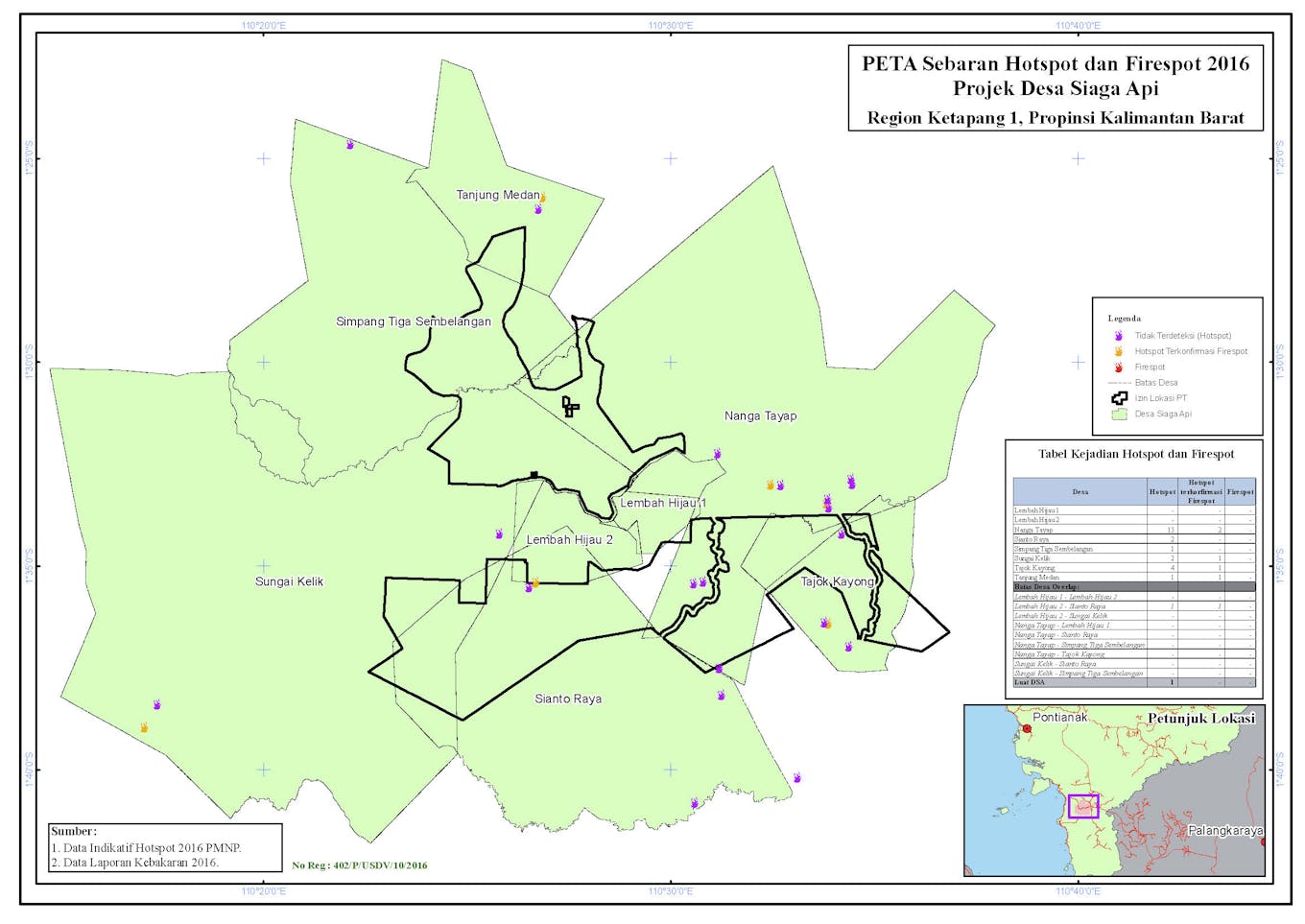

Maps provided by GAR show that there were no fires on PT AMNL’s estates in West Kalimantan in 2016, only a number of hotspots probably caused by self-combusting piles of compost.

Fires and hotspots on PT AMNL’s concession in West Kalimantan in 2016. Image: Golden Agri Resources

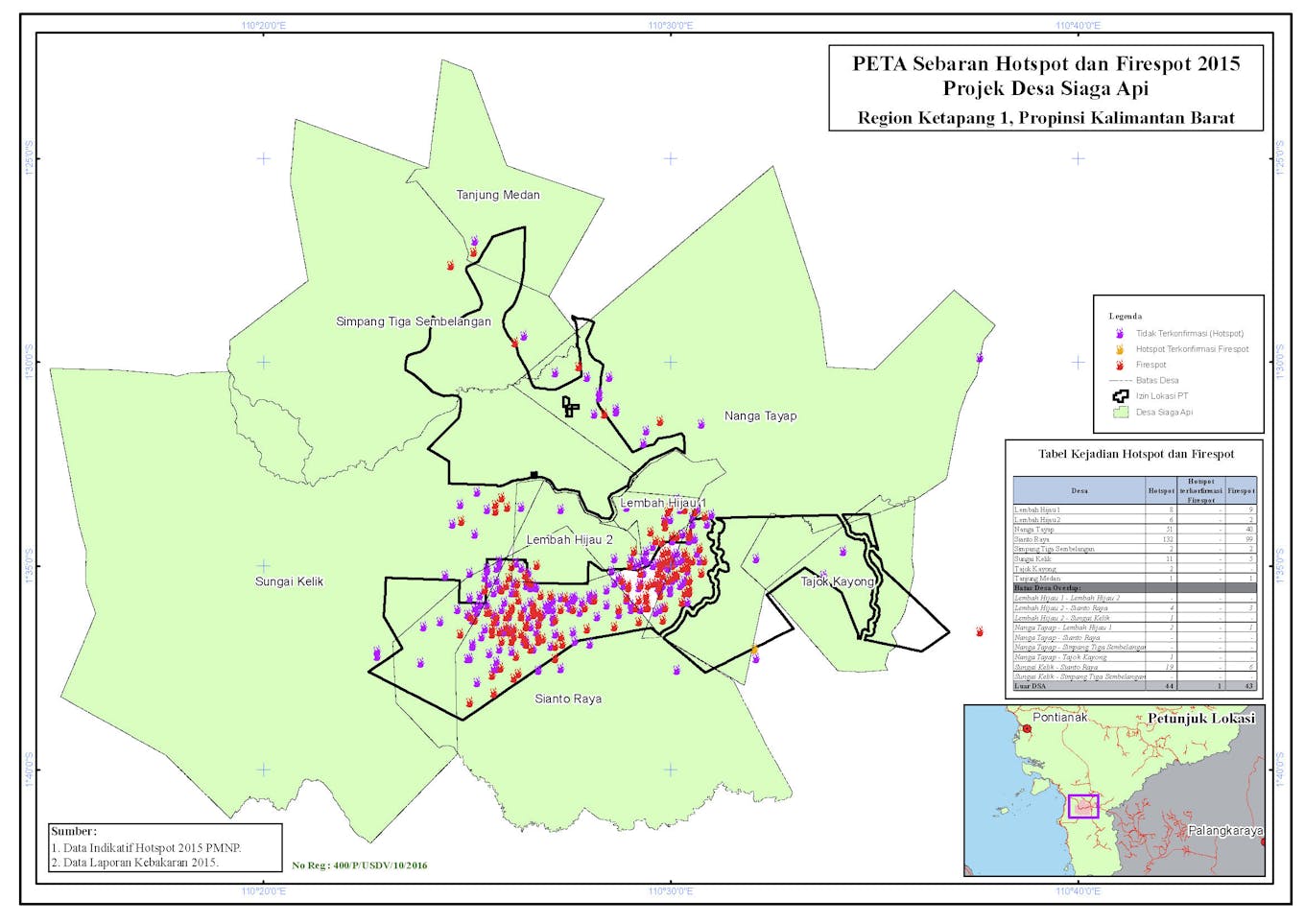

By comparison, fires peppered the estate in 2015.

Fires and hotspots on PT AMNL’s concession in West Kalimantan in 2015. Image: Golden Agri Resources

GAR says the lack of fires in its concession in 2016 is the result of a community engagement programme it launched a year ago to fight the culture of land burning. The company also admits that it got lucky - there was no El Niño in 2016.

Following the fires of 2015, GAR must restore the lost forests in its concessions under order of the Indonesian government, which set up a taskforce, the Peatland Restoration Agency (BRG), dedicated to rehabilitating two million hectares of the country’s ravaged peatland at the start of last year.

Doing so will cost the company roughly US$10,000 per hectare a year, says GAR. To reforest a patch of peatland will take 25 to 30 years to reach maturity (see box below on how to restore a forest), but it can never be restored to what it once was, says Kishokumar Jeyaraj of MEC, a consultancy hired to advise GAR.

Prevention beats suppression

At the heart of GAR’s strategy to fight fires is an effort to improve the livelihoods of villagers living in around its concessions.

The rationale is that if people can live off the land productively, they are less likely to encroach on new land or burn it.

The cover image from a leaflet produced by GAR to warn of the perils of forest fires.

GAR, which in the past has received criticism for how it manages relations with local people when opening up new land for plantations, has invested over the last year in infrastructure, equipment and training for villages to tackle the fires.

The company has also taken a new approach to communicating the perils of burning. Instead of the traditional corporate posters showing militaristic firefighters in heavily branded uniforms, GAR launched a behaviour change campaign that focused on those most at risk from the fires.

In 2015, women, children and the elderly were more than 300 per cent more likely than men to suffer permanent respiratory illness from the haze, so they became the centre of a campaign that ran through the company’s concessions.

“Let’s prevent fires from making our lives miserable again,” says Ibu Sohriah in a video produced by Sinar Mas, the conglomerate that owns GAR.

Cartoon posters also encouraged children to persuade their parents against starting fires and to avoid fire-risky habits.

GAR subsidiary PT Smart ran a pilot community engagement programme called Desa Siaga Api (fire alert villages) in 17 villages in West Kalimantan and Jambi, Sumatra, last year as a first step.

The programme is similar to one pioneered by pulp and paper firm APRIL in 2015 that other agroforestry players have since adopted as part of a Fire Free Alliance, and a platform launched by Sinar Mas sister company APP a short while later.

GAR’s own programme seems to have had the desired effect. There were no fires in the participating villages, so each received IDR100 million (US$7,480) in social infrastructure aid.

This has been followed with a more ambitious programme, called Desa Makmur Peduli Api (which roughly translates to prosperous fire free villages), that teaches villagers how to clear and cultivate land without burning it.

Villagers are given the right seeds to grow palm trees, shown how to create compost, how to use fertilizer and how to cultivate food crops such as chilli, mustard and kale using sustainable farming techniques.

Key to the success of the programme is giving the villages more control over their economic future. In one of the pilot villages named Lembah Hijau 2, the villagers have mapped out their ideal village, and calculated what it will cost to create it through a series of charts and drawings hung on the walls of the village hall. The plan is for the village to be self-sustaining within five years.

An extensive fire prevention effort like this, though not cheap, costs a lot less than putting fires out. It is estimated that for every dollar an agribusiness firm spends on prevention, five can be saved on suppression.

In previous years, villagers have been paid to help with the suppression effort. This strategy hasn’t always worked. Fires were started deliberately so that money could be made from putting them out.

For peat’s sake

BRG, the government’s peatland restoration agency, is now in the process of mapping out Indonesia’s burnt peatland, after which it will begin the tougher task of asking palm oil companies to cover the cost of restoring it.

GAR is luckier than most agribusiness firms in that a relatively small proportion of its plantations grow on peat (roughly seven per cent, although the company has been giving Eco-Business a number of different figures) so it needs to spend less on the recovery effort.

“

Palm oil companies don’t want to increase their commitment [to land conservation], so they try to hide the weak links in their supply chain.

Ian Hilman, campaigner, WWF Indonesia

The company was the first in the palm oil industry to pledge to stop clearing peat forests to make way for plantations in 2011 following a hard-hitting campaign by environmental group Greenpeace.

The campaign featured a man eating a KitKat made from the fingers of an orangutan, a species that has come to symbolise the destruction of Indonesian rainforests by Big Palm Oil. It wasn’t subtle, but it worked.

The campaign paved the way for the now textbook High Carbon Stock (HCS) Approach, a practical way for agribusiness firms to implement a zero-deforestation policy, which was developed developed by GAR, Greenpeace and The Forest Trust.

How to restore a forest

When restoring burnt peatland forest, the first course of action is keep the soil wet.

When consultancy MEC started its land restoration project for GAR, it first surveyed the area using drone cameras to identify the areas where water was flowing out of the peatland through canals, then blocked these outlets.

Preventing the peat from degrading by managing the water table is the critical factor at this stage, and the consultancy says this has been done successfully so far in the 2,000 hectares of forest that GAR needs to restore.

Planting takes place around three years on from the fires, once the ecosystem has stabilised and some ground vegetation has recovered. This is done during the dry season, so the seedlings can establish a foothold when the ground isn’t too soggy.

Kishokumar Jeyaraj, a director at MEC, says that while observers may wish to see instant revegetation this is unrealistic. “The last thing you want is high plant mortality. It depresses people to see dying plants,” he explains.

The species that have emerged naturally are trialed in a test area with new native species to see what thrives, then a mosaic of plant species gradually scaled across a wider area.

In one hectare, around 10,000 seedlings are planted, which costs around US$6,000 for the seedlings alone. Including labour and transportation, to restore a single hectare “properly” may cost around US$10,000, explains Jeyaraj.

It is a diversity of plants that invites animals back to a forest, typically birds first, the fish in riparian areas, and then small and later larger mammals. While patches of forest may support smaller animals, a mosaic landscape of connected forests is needed to support larger fauna, such as endangered orangutans, rhinos and elephants.

GAR claims it will not cultivate any conservation land that burned in the 2015 fires, but not all of it will be returned to nature.

“It’s not a strict conservation effort. The needs of the community need to be taken into account. You can’t exclude them,” says Jeyaraj. “Some marginal areas of land, bordering the villages, will be made available for crop planting without disturbing the core peat area.”

But progress since could have been faster, particularly on the re-rewetting of peatlands, says Anissa Rahmawati, a campaigner for Greenpeace. She adds that cutting oil palm grown on burnt land out of its supply chain completely is no mean feat in a country as vast and complicated as Indonesia.

GAR is under pressure to feed its mills to full capacity, and so oil palm that comes from illegal, burned land is hard to refuse, Rahmawati points out.

Professor Herry Purnomo of the Center for International Forestry Research at Bogor Agricultural University has been studying the value chains of Indonesian palm oil. He says that all of the big six palm oil companies in Indonesia rely on illegal sources to feed their mills.

Tracing the supply chain

But tracing where the oil palm comes from is tricky, GAR says.

Palm fruit bunches are brought to mills from a variety of sources - in trucks, on motorbikes or hand-delivered - and without knowing exactly where the crop comes from means there is no certainty that it was not grown on burnt land.

GAR is not even able to trace palm oil fruit transported from plantations to its own mills, though it hopes to achieve 100 per cent ‘traceability’ by the middle of 2017.

For mills it does not own, GAR hopes to achieve full transparency by 2020.

GAR is now looking to introduce new technology to make traceability easier. Anita Neville, VP of corporate communications and sustainability relationship, says that the company is looking for a solution that can integrate data gathered from smallholders in a way that is accurate and not too costly.

The challenge is finding a simple platform that works in areas of low connectivity and bandwidth like West Kalimantan, and then scaling it, she says. Most of the technology on offer has been developed in Western markets which require high internet access to work.

However, industry watchers say that achieving full traceability should not be difficult. Ian Hilman, a campaigner for Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) Indonesia, is wary that palm oil companies are using non-transparency to hide rogue suppliers linked to deforestation or land conflict.

While most of the big palm oil companies now talk a good zero-deforestation game, and claim their concessions are almost fire free, more pressure needs to be applied to ensure full transparency all the way along the supply chain, says Hilman.

“Palm oil companies don’t want to increase their commitment [to land conservation], so they try to hide the weak links in their supply chain,” he says.

Purnomo argues the same point. “There are a lot of people who depend on illegal oil palm,” he says.

But satellite imagery, combined with maps of palm oil companies’ concessions drawn up by World Resources Institute, means that hiding is getting harder to do.

Consumers and companies that buy palm oil-based products can see for themselves where deforestation is happening, and switch suppliers accordingly.

Have the fires finally burned out?

Now, as 2017’s dry season approaches, with a repeat of the El Niño phenomenon expected by July, the real test of palm oil companies’ fire prevention efforts begins. Will all the money and effort have paid off?

The governor of South Sumatra, Alex Noerdin, said last week said that there will be no blazes in his province in 2017, but GAR’s head of sustainability, Agus Purnomo, says that some fires are inevitable.

However, he predicts that none will be in areas near palm oil plantations. “They will come from other sources, and other causes,” he suggests.

A traditional practice such as land burning cannot be stamped out in a single year, Purnomo says.

“When the next generation becomes the breadwinner, and they’re more concerned about the consequences of fire, then we can start to move away from the practice.”

“But right now, it’s tough. As long as poverty persists, so will fire.”

Check out our accompanying photo essay: In pictures: Indonesia’s fire free villages

Eco-Business visited Golden Agri Resources’ operations in West Kalimantan for this story, but also interviewed academics and non-governmental organisations via Skype. GAR provided accommodation during the plantation visit, and paid for Eco-Business’s travel to and from Indonesia.