If the world does not dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the next decade, Gardens by the Bay, Singapore’s flagship tourist attraction, will become “Gardens beneath the Bay.”

So said Christiana Figueres, one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, at a sustainability event in Singapore four months ago.

Rising sea levels is a problem that the heavily urbanised city-state is taking very seriously. In August, prime minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that S$100 billion (US$72 billion) could be spent on climate change adaptation, including ways to prevent the island from disappearing beneath the waves.

One-third of Singapore, including the central business district, is less than 5 metres above sea level—not as low as the Netherlands, one third of which lies below sea level, but low enough to worry the city-state’s famously foresighted urban planners.

Singapore’s plans to defend against rising seas include building sea walls, polders, and new islands made from reclaimed land. New buildings are to be built four metres above mean sea level, and critical infrastructure at least another metre higher.

“

Sea level rise will be extremely gradual. It won’t be like in the movies.

Tan Szue Hann, managing director, Miniwiz

Speaking to Eco-Business at International Built Environment Week in September, a Changi Airport executive who did not reveal his name said that greenfield sites like the new airport terminal would be safe. “It’s our neighbours downtown who could be underwater,” he said.

Aiming higher

Unlike less fortunate neighbours such as Jakarta, whose steady decline into the sea is to cost the metropolis its status as Indonesia’s capital, Singapore is one of the world’s cities best adapted to climate risks. But exactly how can Singapore protect its valuable built environment from rising seas?

How high will Singapore’s seas rise?

By 2100, the sea level around Singapore will be about a metre higher than it is now, according to projections from Singapore’s National Climate Change Secretariat.

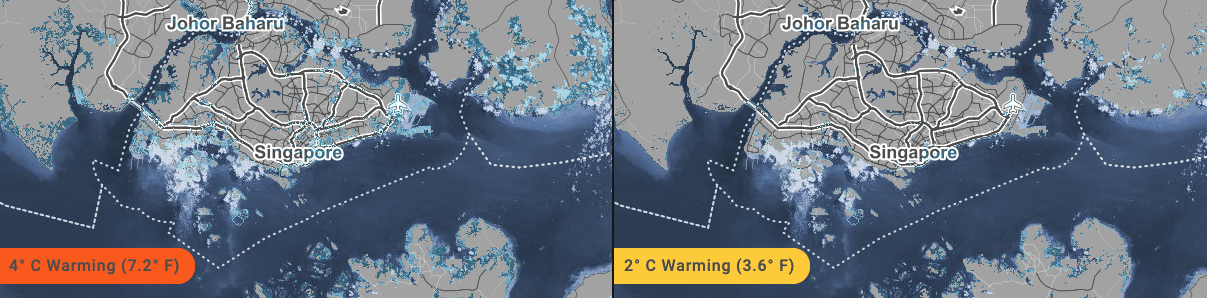

However, a report by non-profit climate news group Climate Central examined the implications of different global warming scenarios of 1.5, 2, 3 and 4 degrees Celsius by 2100, and found that carbon emissions causing 4°C of warming—a business-as-usual scenario—could cause Singapore’s median local sea level to rise by 9.5 metres, submerging 745,000 homes.

Even if carbon emissions were slashed in line with a 2°C warming scenario, 101,000 homes would be submerged in Singapore, with the median local sea level projected to rise by 5.1 metres.

The parts of Singapore most vulnerable to sea level rise are Changi Airport, Marina Bay, the city-state’s most prestigious tourism and business district, industrial towns Jurong and Tuas, and the Southern islands, which include man-made landfill island, Semakau.

The obvious place to start is to lift buildings further above sea level. “This will mean completely changing how we design road and urban infrastructure,” said architect Tan Szue Hann, managing director of circular economy design firm Miniwiz and adjunct professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Ramps and lifts will be needed to provide access to raised buildings, and road networks will have to be re-tarred and elevated as well, Tan told Eco-Business at International Built Environment Week in Singapore in September.

Work to raise roads has already started. The kilometre-long Nicoll Drive on the vulnerable east coast was raised by just under a metre in 2016.

Businesses have also been busy flood-proofing themselves. City Developments Limited, which owns residential properties, offices, hotels, and shopping malls in Singapore, is building all new developments about one metre above ground level in line with government guidelines, raising the kerb heights in car park entrances, and fitting high-risk properties with flood gates.

As the sea around Singapore is currently rising at an average of 4 millimetres a year, planners believe there is time to tweak adaptation plans. “Sea level rise will be extremely gradual. It won’t be like in the movies. We won’t see seawater inundation,” said Tan. “The built environment will have time to adapt.”

Raising the minimum platform level of infrastructure will require a lot of construction material. Tan suggested using aggregates from recycled demolition waste as in-fill to save on concrete. Circular design principles could also be applied to the sea walls to protect the perimeter of the island. Singapore’s already reuses 99 per cent of its construction material, and much of that is used to reclaim land.

Two warming scenarios for sea level rise in Singapore by 2100, calculated by Climate Central. Light blue indicates submerged areas. Image: Climate Central

How high?

As slowly as the sea may seem to be rising, differences in projections for how quickly it might rise in the future (see box) make adaption measures difficult to gauge.

Critical infrastructure such as Jurong Port, which serves the industrial town of Jurong, is faced with a dilemma. Raise the port too high too soon, and millions will be wasted transporting cargo from ship to dock from unnecessary heights. Raise it too low too late, and a busy port that processes 40,000 vessels a year could be sunk.

An architect involved in environmental policy in Singapore, who wanted to remain anonymous, said that some of the port’s height adjustments could be made in stages, and ramps used to level off the differences. But many of the changes would need to be made at the same time, disrupting the work flow of the port.

“Not many businesses in Singapore have started to construct for rising sea levels yet. We need a clearer idea of the rate of sea level rise, so we can work out the latest time we can start building,” Tan Wee Meng, chief technical officer of Jurong Port, told Eco-Business.

No cost estimate has yet been made for raising a facility with a 5.6 km-long berth, but Tan said that it was an investment for which there was no payback. “It’s simply a matter of economic survival,” he said.

Singapore’s climate adaptation measures include the Stamford Detention Tank, which will help prevent flooding in its prime shopping district. Image: Eco-Business

That sinking feeling

Since the 1960s, Singapore has spent billions on drains and canals to cope with flooding, including a S$300 million upgrade of a 3.2 kilometre canal that was completed in September after seven years of work.

Having the money to spend on subterranean flood mitigation infrastructure is a luxury that fast-urbanising and poorer neighbours like Phnom Penh, which has filled in many of its flood-absorbing lakes, do not have.

But will underground infrastructure be enough for Singapore’s built environment to avoid the same fate?

Tan of Miniwiz told Eco-Business that Singapore’s underground water storage infrastructure could not cope with a water influx of the scale of rising sea levels, but could offset some excess water from localised flooding.

Underground detention tanks, like the S$227 million Stamford Detention Tank and Diversion Canal constructed to avoid a repeat of the floods that inundated Singapore’s prized shopping mecca, Orchard Road, in 2010 and 2011, will enable better absorption of some water, and are being built under new buildings.

The increased flow of water through Singapore’s underground infrastructure might even bring about opportunities for the development of hydropower, Jesse Chin, manager of underground utility mapping firm Futurus Construction, told Eco-Business. “The technology isn’t there yet, but one day we will be able to use the water moving around the city to our advantage,” he said.

Nature’s defences

Many existing buildings that lack underground drainage will be harder to protect from the sudden bursts of rain—a climate phenomenon known as “rain bombs”—that will be a more frequent occurrence in a warming world, said the architect working on environment policy in Singapore.

“It’s difficult to build detention tanks for existing buildings,” he said. “So for older districts, you need storm drains that lead to district-level storm water capture systems.”

Without these barriers, Singapore’s rivers and canals could be quickly overwhelmed by bursts of rainfall.

“We’ll need more designs like Bishan Park, which are designed to flood,” he said.

Bishan Park was previously a concrete canal that was converted into a green-flanked river that is naturally able to absorb excess water through the suction power of plants.

The Kallang river basin at Bishan Park, which floods when it rains. This was previously a concrete lined-canal which was remodelled into a naturalised soft-edged accessible river. Image: Jimmy Tan, CC BY 2.0

Singapore, a country almost entirely covered with tropical jungle before rapid urbanisation began, has lost much of its natural ability to absorb water and is left with about 20 per cent green cover; only 0.3 per cent of the 700 square kilometre city-state is covered by primary forests, around the country’s water-critical reservoirs.

Though the country has spent billions on tree-planting to keep faith with the “garden city” vision of former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, much of the “sponge effect” of forests has been lost to concrete.

“The preservation of our remaining forests is crucial, ” said Tan, stressing the need to maintain the natural balance of the water cycle. “Paving over forests removes the absorption power of trees,” he said.

The more forests are removed, the more will need to be spent on man-made sponges.

With Singapore’s population expected to grow from 5.7 million now to up 6.9 million by 2030, the need for more housing and “sensitive building” around natural areas will grow, said the architect who preferred to withhold his name.

“Every time you build, you increase the water run-off, and more vegetation will be need to replace what there was originally—and none of it will be as effective at holding water as if you hadn’t built in the first place,” said the anonymous architect, pointing to new developments such as the “forest town” in Tengah, a 700-hectare estate built in one of Singapore’s few forested areas.

A future afloat?

When Singapore has run out of land to build on, will she look to the sea? Tan pointed to historical examples of floating airport runways in other countries to suggest that floating infrastructure off the coast of Singapore is a very real possibility.

“Floating schools, markets, villages even? We’re not there yet. But that could happen,” he said. In the future, buildings will be built on pontoons that float just off the coast, he suggested.

“Singaporeans could live their lives afloat, like some people do in Amsterdam,” he said.