Local laws are not enough to protect the Philippines from foreign waste dumping, and regulatory loopholes also persist in Thailand and Malaysia, two of Southeast Asia’s top plastic waste importing countries, according to a new report by environmental watchdog Greenpeace and two independent non-profits.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Although hazardous waste is prohibited from entering the Philippines, trash marked as “for recycling” is legal, opening up a loophole that may permit the entry of illegal waste, said Greenpeace Philippines’s country director Lea Guerrero at a press briefing last week for its report urging the country to do more to fight foreign waste imports.

Titled Waste trade and the Philippines: How local and global policy instruments can stop the tide of foreign waste dumping in the country, the report noted how 4.4 million tonnes of mixed plastic waste were sent from the United States to the Philippines in September 2019, despite highly publicised returns of illegal trash shipments to Canada and Hong Kong only a few months before.

Local laws allow for the import of solid plastic materials, but not mixed plastic waste because the latter requires further sorting and would not be entirely recyclable.

“There hasn’t been much of a dip in imported plastic waste even after the repatriation of some waste shipments last year,” Guerrero told Eco-Business, citing United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics up until September last year. “Although experts predicted more plastic waste will be handled at home by developed countries, this is likely true for waste destined for China, but waste that went to other Southeast Asian countries persist at the same level.”

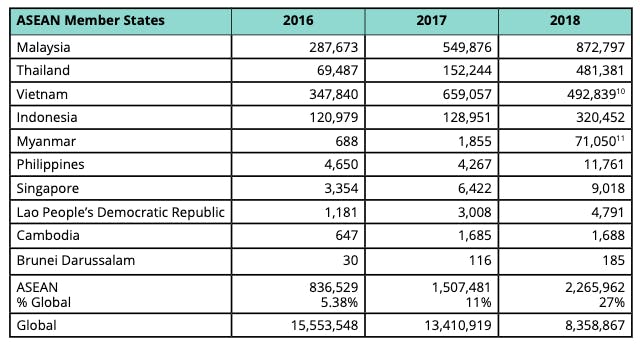

China abruptly banned trash imports from 2018 to cut back on heavy pollution. This left Southeast Asian countries to pick up the slack. For instance, the Philippines’ plastic waste imports soared 150 per cent, from 4,267 tonnes in 2017 to 11,761 tonnes the following year. Most of the waste came from Japan and the United States.

“

Although experts predicted more plastic waste will be handled at home by developed countries, this is likely true for waste destined for China, but waste that went to other Southeast Asian countries persist at the same level.

Lea Guerrero, country director, Greenpeace Philippines

Malaysia, which took the largest share of garbage following China’s import ban, has vowed to prohibit importing plastic waste by 2021.

But a Penang-based non-profit known to be vocal about consumer and environmental issues said despite the government’s campaign, Malaysia continues to receive plastic scraps that are contaminated and non-recyclable.

Mageswari Sangaralingam, research officer of the Consumers Association of Penang, told Eco-Business that Malaysia faces the same policy gaps as Philippine laws.

“The hike in plastic waste imports would have been more, if not for the moratorium on imports imposed by the government. Some of these plastic wastes were smuggled in by false declaration. We do not have good monitoring of the waste that is coming in,” Mageswari told Eco-Business.

Thailand has also declared a ban on foreign plastic waste by 2021, leading to a slight dip in imports due to government mandates in controlling the quota of plastic waste entering the kingdom, according to environmental research organsation Ecological Alert and Recovery Thailand.

Bobby Akarapon, the organisation’s research and technical officer, told Eco-Business that the Thai ministry of industry was allowed to import plastic scraps from foreign countries of not more than 70,000 tonnes for 2019 and not over 40,000 tonnes for 2020. But as of January this year, the government’s trade data has already recorded 22,492 tonnes of waste parings and plastic scrap.

“There really are loopholes in handling and controlling the entry of waste into the country, such as container inspections where only 10 per cent of total waste containers entering the Kingdom are inspected,” Akarapon said.

A previous Greenpeace study also found that a bulk of Thailand’s trash in 2018 was rerouted to Myanmar, which had the most dramatic surge in plastic waste imports in the region after China’s ban, from 1,855 tonnes in 2017 to 71,050 tonnes in 2018. Greenpeace Southeast Asia campaigner Abigail Aguilar pointed to Myanmar’s lack of a legal framework against plastic waste imports for the jump.

The top exporters of plastic waste to Southeast Asia in 2018 were the United States (439,129 tonnes), Japan (430,064 tonnes), Hong Kong (149,516 tonnes), Germany (136,034 tonnes) and the United Kingdom (112,046 tonnes). Other top exporters included Thailand (74,906 tonnes) and Australia (51,057 tonnes).

A previous report by Greepeace shows how Malaysia topped the list in plastic waste imports with almost 900 thousand tonnes as a result of China’s ban in 2017, while Myanmar had the biggest spike in foreign scrap. The Philippines’ plastic imports nearly tripled after the ban. Image: Greenpeace

Basel Ban Amendment: not a perfect solution but …

Greenpeace renewed its call for countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), including the Philippines, to immediately ban all plastic and electronic waste imports, even those meant for recycling, and to sign the Basel BanAmendment.

The Basel Convention was amended in Geneva last year to prohibit the importation of all waste. Within Asean, only Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia have ratified the amendment.

Although critics have said the amendment will not solve the root cause of the waste problem, Greenpeace’s Guerrero said it will at least send a “strong signal” to foreign nations that the Philippines is not a hazardous waste dumping ground.

“The non-ratification of the Basel Ban Amendment leaves countries like the Philippines vulnerable to waste imports. If they ratify it, they would be able to craft local policies in line with the treaty and protect our territory from becoming a dumping ground for wastes camouflaged as ‘recyclables’,” said Guerrero.