The 368-page strategy was published alongside a raft of other documents, including a 202-page heat and buildings strategy, a 135-page Treasury review of the costs of reaching net-zero and numerous other documents. In total, Carbon Brief counted 21 documents covering 1,868 pages.

In a foreword to the net-zero strategy, the prime minister Boris Johnson says meeting the UK’s targets is “the greatest opportunity for jobs and prosperity for our country since the industrial revolution”. The document itself adds that the science on the need to act “could not be clearer”.

With the publication of the strategy, the UK now has firm commitments or “ambitions” to end the sale of combustion-engine cars and vans by 2030, end gas boiler sales by 2035 and have a fully decarbonised power system by the same year.

Grants and market mandates will drive adoption of both electric vehicles (EVs) and heat pumps, while government funding or contracts will support low-carbon electricity supplies from renewables and nuclear, as well as clean hydrogen production and carbon capture and storage (CCS) clusters.

Projections in the strategy show that without the policies it contains, the UK would have missed its sixth carbon budget for 2033-37 by more than 1bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) — a gap larger than the entire budget for five years of emissions.

Although it sets out target-compliant “indicative delivery pathways” for each sector until 2037, it fails to quantify the impact of the new plans and policies it contains, meaning it is not possible to say if the government is now doing — or spending — enough to meet its legally binding goals.

Carbon Brief understands that the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has calculated these numbers. When asked by Carbon Brief, the department would not confirm or deny this.

Finally, the strategy sketches three routes to net-zero by 2050 using electrification, hydrogen and innovation. Electricity supplies roughly double in all cases, primarily from renewables and nuclear.

Why does the UK need a net-zero strategy?

The UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act sets the framework for government action to cut emissions, setting a legally binding long-term goal for 2050 and interim five-yearly carbon budgets.

The Act lays out certain legal requirements, including that the secretary of state, currently Kwasi Kwarteng, must prepare and publish “proposals and policies” sufficient to meet the targets.

The UK has not had an overarching strategy for meeting its climate goals for a number of years and, arguably, the most recent 2017 Clean Growth Strategy was in breach of the Act.

By its own assessment, the 2017 document did not deliver sufficient emissions cuts to meet the UK’s fourth and fifth carbon budgets, covering 2033-2032. Moreover, it was published before the UK became the first major economy to set a target of cutting emissions to net-zero by 2050.

(Some scientists have questioned the widespread adoption of net-zero targets by countries, companies and regions around the world. However, the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said net-zero emissions was a precondition for stabilising the climate.)

The most recent government projections and the independent assessments of the government’s statutory Climate Change Committee (CCC) had all shown a growing gap between UK targets and the policies in place to meet them.

This is where the new UK net-zero strategy comes in, with CCC chief executive Chris Stark tweeting: “We didn’t have a plan before, now we do.”

The baseline for the strategy is to update the government’s projections of how UK emissions would have changed over the next three decades, without the new policies announced over the past year.

This baseline is shown by the blue line below, with the gap between projected emissions and the sixth carbon budget (grey area) being particularly large, at more than 1GtCO2e over five years.

In order to bridge this gap between ambition and implementation, the net-zero strategy sets out a “delivery pathway” in line with meeting the fourth, fifth and sixth carbon budgets (red line).

In response to questions from Carbon Brief, BEIS says the policies in the new strategy are sufficient to “meet carbon budgets four and five” and to “keep us on track for carbon budget six”.

This form of words uses subtly different language in relation to the fourth and fifth periods (“meet”), versus the much more ambitious sixth carbon budget (“keep us on track”).

The strategy itself says it is “presented to parliament pursuant to Section 14” of the Act. This section creates an obligation to set out “proposals and policies for meeting the carbon budgets”.

BEIS tells Carbon Brief: “Our plan is credible, keeps us on track for our ambitious climate targets and meets our legal obligations.”

Beyond domestic legal requirements, the new strategy plays an important role in the context of the UK’s presidency of the COP26 summit, due to take place in Glasgow in less than two weeks.

It forms the basis for meeting the UK’s updated nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement, which targets a 68 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030. The document has also been submitted to UN Climate Change (UNFCCC) as the UK’s Paris long-term strategy.

This means the UK not only has a target for net-zero emissions, but also a plan for meeting it — albeit one with question marks over whether it is fully sufficient. As such, the UK will be in a stronger position with its negotiating partners, as it pushes for more ambitious and concrete climate action.

Regardless of its flaws — discussed in more detail below — the fact that the UK has a detailed plan for net-zero is, by itself, a significant and potentially influential development, argues James Murray, BusinessGreen editor, in a blog on how the strategy should be interpreted. He writes: “[O]ne of the world’s pre-eminent industrialised economies — the crucible of the first industrial revolution — [now] has a detailed plan to fully decarbonise within 30 years. It is a flawed and incomplete plan, but it is a plan. On the eve of COP26 it does provide a workable template for the rest of the world to learn from.”

What does the net-zero strategy say?

Prime minister Boris Johnson has staked his personal reputation on the UK’s net-zero target, making the goal one of his signature manifesto commitments ahead of the last election.

Johnson continues his strong rhetorical support in a foreword to the strategy. He emphasises the opportunities that will be created by the transition to net-zero, touting a “clean and prosperous future” with jobs “everywhere you look” and “vast new global industries from offshore wind to electric vehicles and carbon capture and storage”.

The strategy, Johnson writes, shows how the UK will shift to net-zero “fairly by making carbon-free alternatives cheaper”. Linking the strategy to the recent energy crisis, he continues: “We will make sure what you pay for green, clean electricity is competitive with carbon-laden gas, and with most of our electricity coming from the windfarms of the North Sea or state-of-the-art British nuclear reactors we will reduce our vulnerability to sudden price rises caused by fluctuating international fossil fuel markets.”

In the report itself, a brief annex on the latest climate science, titled “why we must act”, concludes: “The scientific case for strong action on climate change remains definitive.”

The summary of the strategy sets out, in broad terms, what will need to happen to reach its goal, saying: “From heating our homes to filling up our cars, burning fossil fuels releases the greenhouse gases that increase global temperatures.” It explains: “Removing dirty fossil fuels will require the transformation of every sector of the global economy. It means no longer burning fossil fuels for power or heating; it means new ways of making concrete, cement, steel; it means the end of the petrol and diesel engine. These changes are already beginning to happen.”

The document says “every study shows that the costs of inaction are far greater”, but adds that there will inevitably be costs to making the net-zero transition. It adopts four “key principles”:

- Consumer choice: “[N]o one will be required to rip out their boiler or scrap their current car.”

- Polluter pays: “[T]he biggest polluters [will] pay the most…through fair carbon pricing.”

- Protecting the vulnerable: “Government support in the form of energy bill discounts, energy efficiency upgrades, and more.”

- Innovation: “We will work with businesses to continue delivering deep cost reductions in low-carbon tech.”

In terms of the UK’s targets, the strategy says it sets out “clear policies and proposals for keeping us on track for our coming carbon budgets”. It does not say the policies will meet those budgets.

The indicative “delivery pathway” is designed according to “our current understanding of each sector’s potential, and a whole system view of where abatement is most effective”. These sectoral pathways, explained in more detail below, are explicitly not intended to set sectoral targets.

The chart below shows the indicative delivery pathway by sector out to the end of the sixth carbon budget period in 2037, during which greenhouse gases must fall to 78 per cent below 1990 levels.

Each of the coloured fuzzy wedges in the chart represents a single sector, with the blurred edges reflecting uncertainty in the emissions cuts that can be achieved.

The strategy notes: “[W]e must be adaptable over time, as innovation will increase our understanding of the challenges, bring forward new technologies and drive down the costs of existing ones.”

It adds: “We have consistently underestimated how quickly the costs of clean technology would fall to date.”

It lays out investment needs over the years to 2037 amounting to more than £700bn, rising from around £5bn per year during 2020-2022 to around £32bn during the fourth carbon budget period, £48-59bn in the fifth and £52-61bn in the sixth budget, covering 2033-2037.

The strategy says it has, to date, “mobilised £26bn of government capital investment” which will, along with regulations, “leverage up to £90bn of private investment by 2030”.

The strategy then offers three “illustrative” broad-brush pathways to reaching net-zero by 2050 target, explored in more detail at the end of this article.

Although the UK “intends” to meet its next three carbon budgets out to 2037 on the basis of domestic action alone, the strategy says that it “reserves the right” to use international carbon credits to cover part of its targets, including under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

The calculations in the net-zero strategy include the latest estimates of emissions from peatland, which were subject to a major update earlier this year — with the result that the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions are some 16MtCO2e higher than thought.

It also conservatively bases its pathway to net-zero on the higher-end “global warming potentials” (GWPs) estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) fifth assessment report (AR5), even though these numbers are not yet used in the UK’s official emissions inventory.

If the international community decides to adopt the lower-end GWPs from AR5 then “less abatement would be required to meet the same budget”, the document says, providing additional “headroom” that would be a hedge against changes in emissions estimates in the future.

Alongside the strategy itself, the government published another 20 related documents this week, amounting to some 1,865 pages and listed, with hyperlinks, in the table below.

UK policy documents released around the net-zero strategy

The documents include consultations, responses to the CCC’s latest progress report, and a raft of research papers, several of which were hastily removed shortly after publication.

Where possible, Carbon Brief’s table includes alternate links to the removed documents via the Internet Archive. (Please contact Carbon Brief if any of the links are not working.)

One of the removed research papers looks at how it might be possible to cut emissions via behaviour change around diet, travel and other areas. This is in contrast to the net-zero strategy, which stresses that it intends to “go with the grain of existing behaviour and trends”.

For example, on flying, it notes that “expecting the British public to forego holidays abroad would be an enormous political challenge”. Nevertheless, it says targeted interventions could shift behaviour, such as higher taxes on frequent flyers or greater provision of high-speed rail.

The strategy and associated documents this week follow the publication of several other key central government climate policies and pledges over the past year.

These include a transport decarbonisation plan, an energy white paper, a plan for industrial decarbonisation, a hydrogen strategy, the prime minister’s 10-point plan, a North Sea “transition deal”, an English strategy for peat and afforestation and a food strategy for England.

What about the Treasury net-zero review?

The most prominent of the documents released around the government strategy is the Treasury’s net-zero review, following a process initiated in 2019 in response to the CCC’s advice.

The review was intended to assess the distribution of costs and benefits from net-zero, as well as the impacts on the government’s finances and the competitiveness of the economy.

It published an interim report in December 2020, which concluded: “The combined effect of UK and global climate action on UK economic growth is likely to be relatively small.”

The Treasury’s position has been heavily briefed to the media in recent months and even this week garnered more prominent coverage in many papers than the net-zero strategy itself.

The review, which does not include a foreword from the chancellor or a ministerial colleague, makes various supportive statements on the government’s net-zero strategy. It begins: “Global action to mitigate climate change is essential to long-term UK prosperity. The majority of global GDP is now covered by net-zero targets. As the world decarbonises, UK action can generate benefits to businesses and households across the country.”

The review adds that, “overall”, a successful and orderly transition to net-zero “could realise more benefits…than an economy based on fossil fuel consumption”. It also points to the potential co-benefits of climate action, such as improved air quality, worth some £35bn, it says.

The Treasury says that current estimates could “understate the economic cost to the UK as the climate heats up” and that the shift to net-zero “could provide a boost to the economy”, with the required investment potentially contributing to growth.

Overall, the Treasury says the impact on GDP as a result of efforts to reach net-zero are “likely to be relatively small and dwarfed by the costs of global inaction”. It points to evidence for the CCC that found the impact on UK GDP in 2050 could be “slightly negative to slightly positive (-0.63 per cent to +1.48 per cent depending on the model choice)”.

In contrast to the potentially understated costs of warming, the review emphasises that abatement costs are “speculative” and that “technology costs have typically fallen faster than anticipated”.

The Treasury notes that total UK investment levels are the lowest in the G7 group of major economies, as shown in the chart below, adding: “The investment required to decarbonise the UK economy could help to improve the UK’s relatively low investment levels and increase productivity.”

Nevertheless, the Treasury pushes back on the idea of using higher public borrowing to fund the shift to net-zero, arguing that this would unfairly “pass on costs to future taxpayers” and would fit with “polluter pays”.

This position has been criticised as “unconvincing”, with Nick Mabey, a former Treasury official and chief executive of the E3G thinktank, pointing to the “negative real interest rates” currently available for government borrowing.

Instead, the Treasury notes the fiscal risk posed by the “erosion” of fuel duty, as the economy switches towards EVs, with a potential need for “new” taxes to replace lost revenue. (This prompted inaccurate headlines saying the Treasury was calling for “higher” taxes to fund net-zero.)

The review has limited analysis of the distributional impacts of net-zero, however, it does say that average household energy bills would be expected to be similar in 2050, for a home with a heat pump and EV, as compared with one that currently has a gas boiler and petrol car.

It argues that while poorer households already tend to have lower emissions, they may also be least able to afford the one-off costs of moving to low-carbon alternatives. As such, it backs “targeted” public spending to support decarbonisation in low-income households. It adds that this is reflected in “a number of government schemes, as set out in the heat and buildings strategy”.

In terms of how the government should drive the shift to net-zero, the Treasury review makes its preferences clear on the appropriate mix between pricing, regulation and public support.

It emphasises “competitive markets”, saying these are “likely to deliver the most efficient transition across the economy” — even though “carbon pricing on its own will not decarbonise all sectors”.

As such, it says the UK is committed to “exploring” the option of expanding its emissions trading scheme (UKETS) beyond its current coverage in industry and the power sector, to the two-thirds of current emissions that are not yet included.

(It says that carbon border adjustment mechanisms, where imports are subject to a form of carbon pricing to prevent “carbon leakage”, have “intuitive appeal [but] they are not straightforward”.)

The Treasury does also recognise the “central role” that “well-targeted and designed regulation” will continue to have in climate policy. And it accepts that public spending will be important “in some cases”, particularly to mitigate “acute distributional impacts”.

What does the net-zero strategy say about each sector?

The net-zero strategy includes a breakdown of what will be required in the coming years from each area of the economy in order to remain on track for net-zero by 2050.

It includes charts showing “indicative” pathways up to 2037, which the government says will be used as a guide to ensure that it is on track to achieve its targets, including upcoming carbon budgets and the UK’s nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement.

While much of the information in the strategy is familiar from previous government announcements and the array of sectoral plans that have been published this year, it also includes many updated policies and new targets.

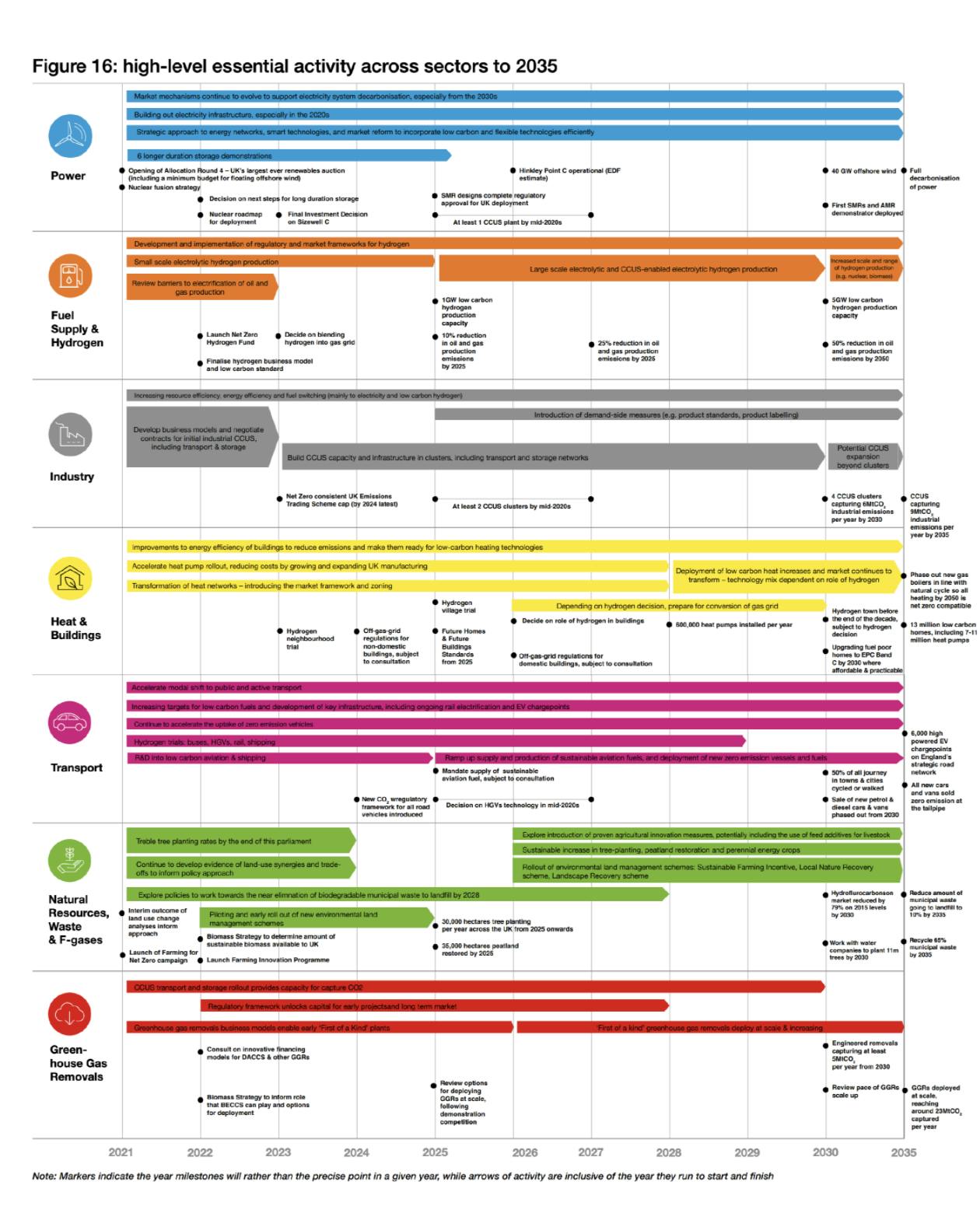

The timelines below provide an overview of key developments expected over the next 14 years on the path to net-zero. Below them, Carbon Brief has picked out the major new announcements for each sector.

Timelines showing “essential activity across sectors” in the government’s pathway out to 2035. Source: Net-zero strategy

Net-zero strategy: power

The UK’s power system has already seen the biggest drop in emissions of any sector, falling 72 per cent between 1990 and 2019. In the coming years, this trajectory is expected to continue.

A key component of the net-zero strategy is the deadline of 2035 for all electricity to come from “low-carbon sources”.

This confirms a recent pledge made by the government to “decarbonise the UK’s electricity system by 2035”, which itself is in line with a recommendation from the CCC for reaching net-zero by 2050. It strengthens an energy white paper target of an “overwhelmingly decarbonised power system during the 2030s”.

The chart below shows the government’s “indicative” pathway for electricity sector emissions — which appears to contradict the “fully decarbonised” by 2035 target. In fact, the report says that to meet the UK’s climate targets power emissions “could fall by… 80-85 per cent by 2035” compared to 2019 levels.

Nevertheless, a table on the “deployment assumptions” which apparently underpin the pathway has “low-carbon” generation at 99 per cent in 2035.

Carbon Brief understands that the remaining 15-20 per cent of emissions will come from gas-powered plants equipped with CCS technology or facilities powered using waste. Both are classed as “low-carbon” sources, even though CCS only captures 80-90 per cent of CO2 and waste plants also produce emissions.

It may also include a small amount of unabated natural gas, which the document says will run in the future “only when the system most needs it for security of supply”.

Achieving this target will require additional funding of around £150-270bn in public and private investment, the government says.

The document also recognises that across this timescale the power system must meet a 40-60 per cent increase in demand as larger shares of transport and heat are electrified.

Besides reiterating previous commitments to wind power, the government says that the required “step change” in renewable deployment will be achieved primarily through the existing contacts for difference (CfD) scheme and a review of auction frequency will be held to support this. The energy white paper, by contrast, appeared to suggest a gradual move away from the CfD model.

The strategy emphasises the need for system reliability and flexible technologies including carbon capture and storage (CCS) generation and nuclear.

The strategy includes a new £120m future nuclear enabling funds to support advanced nuclear technologies, including small modular reactors (SMRs). By around 2030, it aims to have the first SMRs and an advanced nuclear demonstration project deployed.

However, a rumoured confirmation of funding for the Sizewell C new nuclear plant appears to have been delayed. The government intends to bring “at least one” large-scale nuclear project of this type to the point of final investment decision during this parliament, “subject to value for money and approvals”.

To remain on track for the sixth carbon budget, the strategy says there will need to be “significant expansion” of CCS power generation beyond the white paper pledge of one power plant by 2030.

The government says it will use a new dispatchable power agreement — similar to the CfDs used for renewable power projects — to bring forward at least one CCS plant to the mid-2020s.

Net-zero strategy: domestic transport

Transport makes up the largest share of UK emissions — 27 per cent — of which more than half comes from cars. Ending the sale of fossil fuel-powered cars and vans by 2030 has long been one of the most high-profile elements of the government’s net-zero plans.

The chart below shows a similar trajectory out to 2037 as the chart featured in the recent transport decarbonisation plan, with emissions from the sector — excluding international aviation and shipping — dropping significantly over the next decade.

It envisages emissions from domestic transport falling 65-76 per cent by 2035, from 2019 levels, and anticipates some residual emissions from the sector even in 2050 that will have to be removed.

Most of the policies and funding schemes included in the strategy are “already underway”, according to the document, and have been widely publicised. This includes money for buses, walking and cycling infrastructure.

Perhaps the most important new feature of the strategy is the announcement of a zero-emission vehicle mandate for carmakers, a policy recommended by the CCC that has been out for consultation since the transport decarbonisation strategy in July.

This mandate will require manufacturers to gradually scale up the number of vehicles they sell from 2024, providing a clear industry signal and establishing a mechanism for the government to achieve its 2030 target for the phaseout of petrol and diesel models.

Funds to support grants for prospective electric vehicle owners and the expansion of charging infrastructure were announced last year. The strategy includes an additional £620m to bolster these funds.

It also allocates £350m from its pre-existing £1bn automotive transformation fund to “support the electrification of UK vehicles and their supply chains”.

However, to achieve the levels of emissions reductions in the sector required for the government’s “delivery pathway”, it says additional public and private investment of around £220bn will ultimately be required.

The government is still either conducting or assessing the results from consultations on phaseout dates for the sale of petrol and diesel heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), buses, coaches and motorbikes.

Following £20m road-freight trials — which were referenced in the transport decarbonisation plan and tested technologies, such as hydrogen-powered trucks, batteries and “electric road” systems — the government says it is now ready to expand three key technologies to large-scale trials.

Net-zero strategy: industry

Heavy industry is a sector that is given considerably more clarity and ambition in the new net-zero strategy.

Industries, such as steel and cement production, are major sources of emissions and often involve processes that are difficult to decarbonise.

As a result, on an “indicative” emissions pathway set out in the strategy, while emissions drop considerably by 2050 (87-96 per cent compared to 2019), the document also acknowledges the need to remove any remaining emissions using removal technologies.

It also estimates a drop of 63-76 per cent by 2035, which is roughly consistent with the drop of at least two-thirds that the industrial decarbonisation strategy, released earlier this year, concluded would be necessary to stay on track for net-zero.

Building on that strategy, the government says that its new pathway requires “increased levels of fuel switching and iron and steel decarbonising in the 2020s and early 2030s”, adding that the document goes “further than the [industrial decarbonisation strategy] in several areas”.

Low-carbon hydrogen and CCS will be important for decarbonising processes that are very reliant on fossil fuels, but both will require significant scaling up.

Overall, the new strategy more than doubles the previous CCS target of 10m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) captured across the economy by 2030, which was announced in the prime minister’s 10-point plan last year.

By that date, the government now aims to capture between 20-30MtCO2 per year, rising to 50MtCO2 by the mid-2030s

While the previous strategy included 3MtCO2 being captured annually at industrial sites by 2030, the net-zero strategy involves 6MtCO2 captured per year by 2030 and 9MtCO2 by 2035.

The government also says it has “kicked off the process to decide the first carbon capture cluster locations in our industrial heartlands”, identifying the Hynet and East Coast Clusters, which include Teesside and the Humber, Merseyside and North Wales as locations that will be prioritised, with the Scottish Cluster in the north east of Scotland as a backup.

The hydrogen strategy estimated that hydrogen use as an industrial fuel could range from 10-20 terawatt hours (TWh) per year by 2030. The net-zero strategy says this “may need to increase up to 50TWh by 2035” to deliver on future climate targets.

Such a shift, it says, “would be driven by a growing number of sites having access to low carbon hydrogen, further technology development to enable an expanding range of processes to switch to hydrogen and a shift in the associated costs, such as the price of carbon, to make hydrogen an increasingly competitive fuel option”.

The government notes that it has set up the industrial decarbonisation and hydrogen revenue

support (IDHRS) scheme to support its new hydrogen and industrial CCS business models. It commits £140m to establish the scheme. This includes £100m of funds to award contracts of up to 250 megawatts (MW) of electrolytic hydrogen production in 2023.

The strategy also includes much faster gains from resource and energy efficiency, which in the industrial decarbonisation strategy are estimated to save a total of around 13MtCO2 per year by 2050. In the new modelling, these savings already reach 11MtCO2 by 2035.

Other developments cited are greater realisation of the “benefits of demand side measures and carbon pricing”, as well as consulting on a net-zero consistent UK emissions trading scheme (ETS) cap to incentivise emissions cuts in industry.

It states that achieving these levels of emissions reductions will require additional public and private investment of at least £14bn, adding that energy and resource efficiency will offset some of these costs.

Net-zero strategy: heat and buildings

On the government’s indicative trajectory to net-zero, emissions from heat and buildings will have to buck their decade-long flatlining trend and drop by up to 100 per cent by 2050.

In order to meet such a target, the strategy’s modelling sees emissions from the nation’s housing stock falling 47-62 per cent by 2035.

With a separate heat and buildings strategy published on the same day at the net-zero strategy, there are no new policy announcements in the net-zero strategy for this sector.

As in the strategy, the government emphasises the importance of improved energy performance in homes, aiming to phase out fossil-fuel boilers by 2035 and significantly ramping up sales of electric heat pumps to replace them.

It also discusses the potential for shifting energy levies “away from electricity to gas over this decade” — a move seen as important for encouraging uptake of heat pumps.

The strategy does feature some additional details about deployment assumptions the government is making for different technologies so that emissions reductions by 2035 follow a similar course to those seen in the chart below.

It indicates that a total of 7-11m heat pumps will be installed in homes by 2035, up from 200,000 in 2019. The higher number is part of the government’s “high electrification” scenario in which hydrogen has “not proven to be feasible, cost-effective or preferable”.

The document also notes that 0-4m homes will rely on 100 per cent hydrogen for heat — a wide range that reflects the uncertainty around the role for hydrogen in this sector.

The government has delayed a firm decision on hydrogen in heating until 2026, but it is worth noting that even in its “high hydrogen” scenario, heat pumps are the dominant source of low-carbon heat in 2035, installed in 7m homes compared to 4m for hydrogen.

A “core commitment” outlined in the strategy is to “reduce bills, whilst improving comfort, health and home value” by ensuring as many homes as possible achieve the energy standard of Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) band C by 2035.

It reiterates various activities it is pursuing to this effect, including potential policies to ensure both private rented and owner occupied homes have better energy performance.

Net-zero strategy: agriculture, forestry and other land use

Farming, as well as land use more generally, have been identified as some of the weakest areas of the net-zero strategy, with fewer concrete targets for the coming decades than other sectors.

In its future scenario, the government anticipates significant emissions remaining in this sector by 2050 that will need to be compensated by both nature-based and engineered greenhouse gas removals.

As the chart below shows, it sees emissions falling by 67-75 per cent over this timescale. By 2035, these emissions are expected to fall by 39-51 per cent.

To reach this point, the strategy reiterates some of the government’s previous commitments to tree-planting, including its aim to triple annual tree-planting rates in England by the end of this parliament.

It also includes a new commitment to restoring 280,000 hectares of peat in England by 2050, an improvement on the 35,000 hectares it had previously pledged to restore by 2025.

However, this is still just 20 per cent of the UK’s peatland and campaigners have pointed out it falls short of the CCC’s recommendations for preserving these high-carbon stores. There is also no reference to a ban on the controversial burning of peatlands by grouse moor owners.

The government said achieving its targets would require additional public and private investment of around £30bn. It commits an additional £124m to its £640m nature for climate fund.

Unlike other major sectors, there is no target for cutting emissions from agriculture, despite it being responsible for 10 per cent of UK emissions.

Instead, it references 75 per cent of farmers in England being “engaged in low-carbon practices” by 2030, increasing to 85 per cent by 2035.

Net-zero strategy: international aviation and shipping

The UK’s share of international aviation and shipping emissions, which will be formally included in its climate targets for the first time as of the sixth carbon budget, are not expected to change significantly in the near future.

In the government’s scenario, emissions from these sources are expected to fall by around 12 per cent by 2035. As the chart below shows, these sources will likely still be major emitters even in 2050.

The government says it will “address aviation emissions through new technology such as electric and hydrogen aircraft, the commercialisation of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) [and] increasing operational efficiencies”.

Specifically, it says there will be a SAF mandate to enable the delivery of 10 per cent SAF by 2030, plus support for the UK industry with £180m new funding to develop SAF plants. However, the assumption in the strategy’s pathway to 2035 is that only 6 per cent of aviation fuel will be sustainable.

The results of the first consultation on SAF are currently being reviewed, with a second due in 2022.

It also says it will cut emissions from this sector using market-based measures, “while influencing consumers to make more sustainable choices when flying”. However, ultimately, the sector will need to rely on sizable emissions removals in order to be net-zero compliant.

The strategy also mentions extending a clean maritime demonstration competition to a multi-year programme, to support the development of clean maritime vessels and infrastructure.

This is part of a plan to create a UK Shipping Office for Reducing Emissions (UKSHORE) to “transform the UK into a global leader in the design and manufacturing of clean maritime technology”. By 2035, the strategy envisages 28 per cent of international shipping fuel being low-carbon.

Net-zero strategy: greenhouse gas removals

As trajectories for other sectors — particularly agriculture and international transport — demonstrate, even by the net-zero deadline of 2050 there are still sectors that are expected to be producing some residual emissions.

This means there is a need for greenhouse gas removals using nature-based methods such as tree planting and negative emissions technologies such as direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). The latter remain largely unproven at scale.

Following a consultation, and in line with recommendations by the CCC and National Infrastructure Commission, the government has set the ambition of deploying at least 5MtCO2 per year of engineered removals by 2030.

In its delivery pathway, this then scales up enormously to around 23MtCO2 by 2035, albeit with a wide potential range based on “sector-specific and wider economy developments”.

By 2050, the strategy states that engineered removals of 75-81MtCO2 per year will be required to help compensate for residual emissions. More emphasis on behaviour change, such as taking fewer flights or eating less meat, would mean less pressure on this largely unproven technology.

Government plans for this sector are still relatively underdeveloped, although the strategy highlights a consultation on “innovative financing models” for removal technologies and its biomass strategy, both next year, as opportunities to develop BECCS and DACCs.

The government states that staying on this path will require additional public and private investment of around £20bn, and reiterates a previous funding commitment of £100m for DACCs and other removal technologies.

Net-zero strategy: other sectors

The strategy includes sections on a handful of other sectors including the UK’s oil and gas industry, waste and F-gases.

In March, the government published its North Sea transition deal, which contained an agreement that the oil-and-gas sector would cut its emissions by 50 per cent by 2030.

However, this only covered emissions from fossil-fuel production rather than use. Campaigners have pointed out that the deal allowed companies to continue exploring for oil and gas.

The net-zero strategy repeats a previous pledge by the government to introduce a new “climate compatibility checkpoint” to ensure licences awarded are “aligned with wider climate objectives”.

It also says that while the current gas price crisis underlines “the need to get off hydrocarbons as quickly as possible”, this must be done in a way that protects jobs, investment and maintains energy security.

As for waste, the government says it will bring forward £295m in funding to help local authorities in England implement free food waste collections from 2025, with an overall target of no biodegradable municipal waste going to landfill from 2028.

Finally, F-gases — greenhouse gases which can be used in heat pumps and air-conditioning units — are being rapidly phased out and by 2050 are set to be “predominantly replaced by alternative gases or technologies”.

The government says it will complete an F-gas regulation review and assess “whether we can go further than the current requirements and international commitments”.

How will the UK reach net-zero overall?

The net-zero strategy says that completely decarbonising the economy over the next three decades “will be a journey of unprecedented opportunity and change”.

However, it also emphasises the challenges that will be involved, with changes needing to be made in every sector and in all aspects of our daily lives, from travel to heating and industry.

Recognising the interconnectedness of changes in different sectors, the strategy takes a “whole-economy perspective” and uses a “systems approach” to ensure coordination. This means, for example, making sure that EVs have access to sufficient low-carbon electricity supplies, but are also capable of smart charging so as to manage impacts of new sources of demand.

After the end of the sixth carbon budget period in 2037, the net-zero strategy eschews detailed sectoral pathways in favour of three “illustrative scenarios”, reflecting the greater uncertainty looking further into the future.

It says there are a range of ways to meet net-zero, with the exact route depending on the cost and availability of key technologies, as well as the choices made by individuals and businesses.

However, it highlights several “key green technologies and energy carriers” that feature strongly in all three scenarios and help to radically reduce demand for fossil fuels. These are:

- Electricity, where renewables and nuclear meet demand that roughly doubles by 2050;

- Hydrogen, which “complements” electricity “especially in harder to electrify areas like parts of industry and heating, and in heavier transport, such as aviation and shipping”;

- Carbon capture and storage, used in the power sector, industry, hydrogen production and greenhouse gas removals using DAC and BECCS;

- Biomass, used for negative emissions in combination with CCS and to make fuels for industry, transport and buildings.

Although the three 2050 scenarios reflect varying reliance on these technologies, demand for clean electricity doubles in all cases and power generation is dominated by renewables and nuclear.

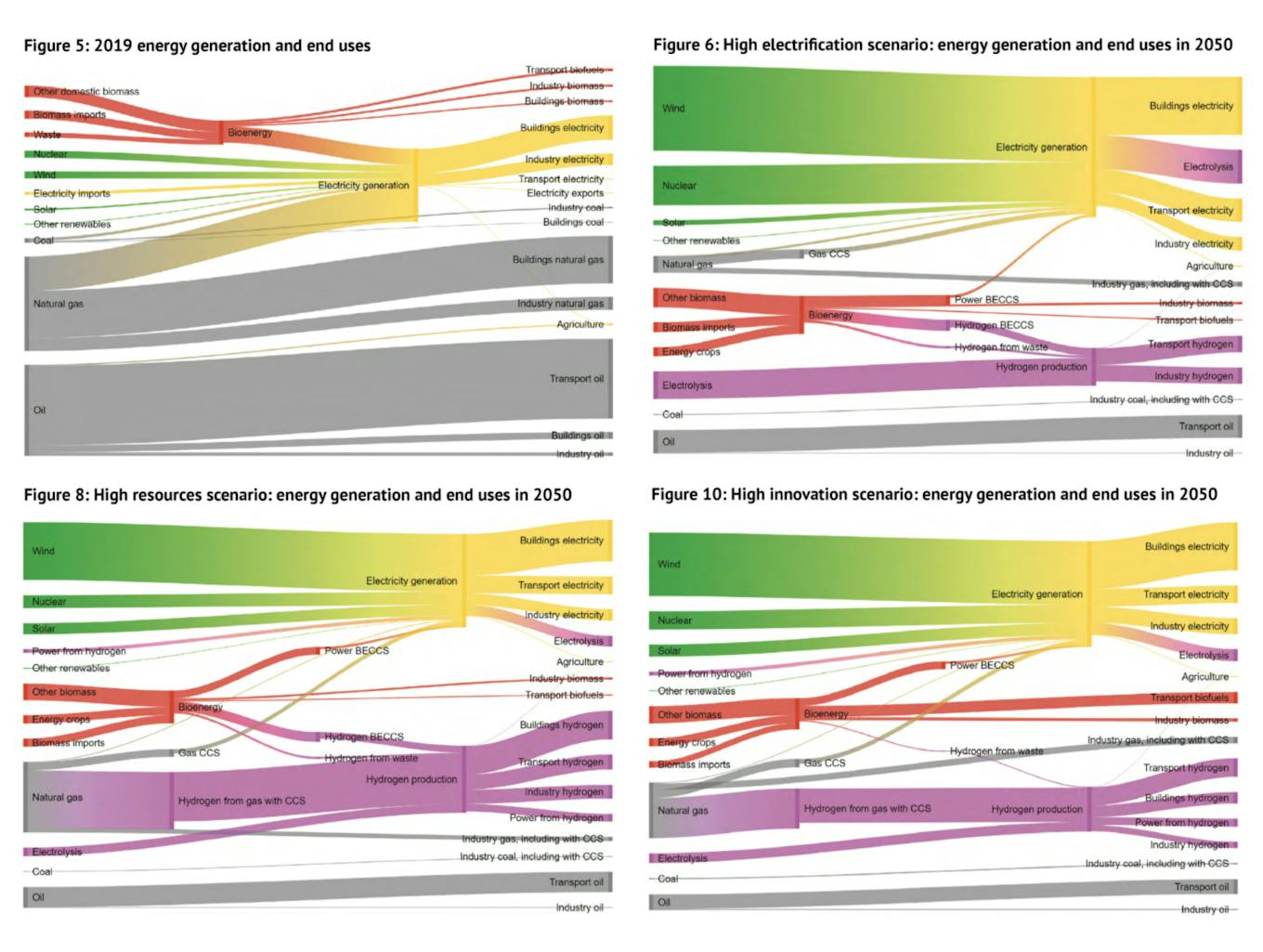

For comparison, the UK’s energy use in 2019 is shown in the top-left chart below. Energy supplies from fossil fuels (grey), biomass (red) and zero-carbon fuels (green) are shown on the left, with some of these converted into electricity (yellow). Energy demand is shown on the right.

The other charts illustrate the three 2050 scenarios, named “high electrification”, “high resources” and “high innovation”. In each case, fossil fuel use is dramatically reduced and the picture is dominated by electricity from renewables and nuclear.

Hydrogen (purple) features in all scenarios, but its scale and end use varies considerably, with building heat only featuring in one. In the scenarios, residual gas demand provides electricity generation with CCS and, in some cases, “blue” hydrogen. Residual oil use is largely for aviation.

Sources of energy in the UK, by fuel and vector, and end uses by sector. Top left: The situation in 2019. Other charts: Three illustrative scenarios for meeting the net-zero by 2050 target.

Key differences between the scenarios include the extent to which building heat is electrified, with effectively 100 per cent of buildings using heat pumps in “high electrification”. In the “high resources” scenario”, heat pumps are “constrained” to 40 per cent of buildings and some 14m homes use hydrogen.

There is also wide variation between scenarios on the source of hydrogen, with “blue” hydrogen from natural gas with CCS making up 75 per cent of the total in “high resources”, but none in “high electrification”, where it is made instead from electrolysis or biomass.

The strategy explains that the 2050 scenarios were developed using the UK TIMES model, based on assumptions about technology costs, availability, performance and deployment rates.

It notes “a number of limitations” with the model, including technology cost reductions not being affected by deployment rates and political or social barriers being excluded. It also does not consider industrial benefits, benefits or risks to the economy or behavioural considerations.

In common with the other integrated assessment models (IAMs) used to assess pathways to meeting climate goals, the UK TIMES model has certain biases, with one modeller noting that it can be “often quite CCS-heavy” and calling for government to use a range of models instead.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.