Next week, countries are supposed to finalise a deal on limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from international shipping.

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) environment meeting in London is expected to set a concrete target for shipping emissions in the coming decades. After the Paris Agreement and a deal on emissions from international aviation, shipping is the last sector to contribute to global climate action.

However, following a week of preparatory talks, the level of ambition which will be agreed is still very much up in the air.

A deal decades in the making

Shipping is responsible for around 2-3 of the world’s GHG emissions, about the same as Germany. However, shipping, like aviation, is not directly included in the Paris Agreement.

Instead, responsibility for cutting the emissions of these two sectors is assigned to their respective specialist United Nations (UN) agencies: the IMO and the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). Countries agreed an aviation deal, based on an offsetting approach, in 2016, leaving international shipping as the only sector not covered by a global deal.

While GHGs from shipping fall under the responsibility of the IMO, the agency is not equivalent to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in that it is responsible for regulating international shipping at large, as well as pollution from ships. Therefore, regulation of GHGs only makes up a small part of its remit.

A climate shipping deal has been long in the making. The IMO first adopted a resolution on GHG emissions in 1997, the same year the Kyoto Protocol was adopted. This protocol officially handed responsibility for marine emissions to the IMO.

Extract from Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997

However, talks stalled again and again. There are several issues to overcome. There is concern that the impacts of any deal will fall disproportionately on flag states with many ships registered. Just six flag states – Panama, China, Liberia, the Marshall Islands, Singapore and Malta – account for over half of global shipping CO2 emissions.

There also arguments that there is not yet enough data on ship emissions to consider setting a global target, or that shipping does not have the technical means to decarbonise.

Meanwhile, the IMO’s “non-discriminatory” guiding principle of treating every ship the same is seen to be at odds with the UNFCCC principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”, where efforts depends on different national circumstances.

Several NGOs have also criticised the IMO for allowing too much corporate influence at the talks, which they say has contributed to holding up an emissions reduction deal.

While the IMO adopted two technical measures on energy efficiency in 2011 and will require ships to report on their fuel consumption from 2019, no overall cap or reduction on shipping emissions has been set. Discussions on a market-based mechanism also collapsed in 2013.

In 2015, however, during the lead up to the Paris climate talks, the Marshall Islands created new momentum by submitting a resolution asking the IMO to adopt a GHG reduction target consistent with keeping warming below 1.5C. This gained support, and the IMO adopted a GHG reduction roadmap, which said an “initial strategy” should be adopted in April 2018, with a revised strategy agreed in 2023.

This initial strategy, set to be agreed by next Friday, is expected to contain a “vision statement”—an overarching aim for the strategy to achieve—some kind of quantified target and an action plan towards the revised strategy in 2023. It could also includes short term measures to be implemented up to 2023.

Despite being called an “initial” strategy, the deal could therefore set the boundaries and tone of climate ambition from shipping for decades to come.

Country positions

Ahead of this week’s discussions in the IMO’s GHG “working group”, countries had the chance to offer their vision for the shipping GHG strategy. The working group will report to the more formal “Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) 72” next week, before a final agreement is decided.

The various country proposals include wildly different levels of ambition.

The Marshall Islands, supported by some other Pacific island states, want complete decarbonisation of global shipping by 2035. (Significantly, this call comes from one of the world’s leading flag states.)

EU member states, including the UK, have supported a “70-100 per cent” reduction on 2008 emissions by 2050, and a 90 per cent reductions in the carbon intensity of shipping.

Japan has proposed that emissions be cut to 50 per cent below 2008 levels by 2060, along with a 40 per cent improvement in ships’ fuel efficiency by 2030. Japan also includes the idea of “amendments” to the goal, pending an IMO review of its achievability at a later date.

Other submissions show even lower ambition. The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) and other trade groups have proposed simply capping shipping emissions at 2008 levels, along with a 50 per cent efficiency improvement by 2050. A group of low-ambition countries, including Argentina, Brazil, China and Turkey, argue against any absolute emissions cap, saying it could result in carbon leakage to other transport modes such as rail and air.

This spectrum of ambition has led some to describe Japan’s proposal as a fair “compromise”. However, it is far below what is considered to be in line with the Paris Agreement’s “well below 2C” commitment, let alone 1.5C (see below).

Meanwhile, Carbon Brief understands a new “compromise” deal has been proposed by the chair of this week’s IMO working group session. This would bring Japan’s 50 per cent reduction target forward by 10 years, to 2050. Norway’s government and shipowners’ association have also backed this proposal.

However, the Marshall Islands and several other low-lying Pacific nations say they will refuse to endorse a proposal not expressed as a range of 50-100 per cent, which would keep the door open to a shipping target in line with the 1.5C temperature goal.

The EU IMO voting bloc has also reportedly this week agreed to push for a minimum 70 per cent reduction target by 2050, with an ultimate aim of raising this to 100 per cent. The stance was agreed despite opposition from Greece, Cyprus and Malta, all leading flag states.

The EU position comes with a credible threat of unilateral action. The European Parliament recently approved a proposal to include shipping in the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) from 2023, unless the IMO approves an “ambitious emission reduction objective” by 2021.

While this proposal would have to be agreed in negotiations with EU member states and the EU commission, a report this week indicated EU member states could back such unilateral action on shipping at a meeting later this month, if they are not happy with the outcome at the IMO. Including shipping in the EU ETS is strongly opposed by shipping industry bodies and the IMO.

Many countries – at least in theory – agree to putting shipping emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. The “Tony de Brum” declaration, launched in December last year and now signed by 44 countries, calls on shipping to take “urgent action” to contribute to meeting the 2C and 1.5C goals of Paris.

Emissions share

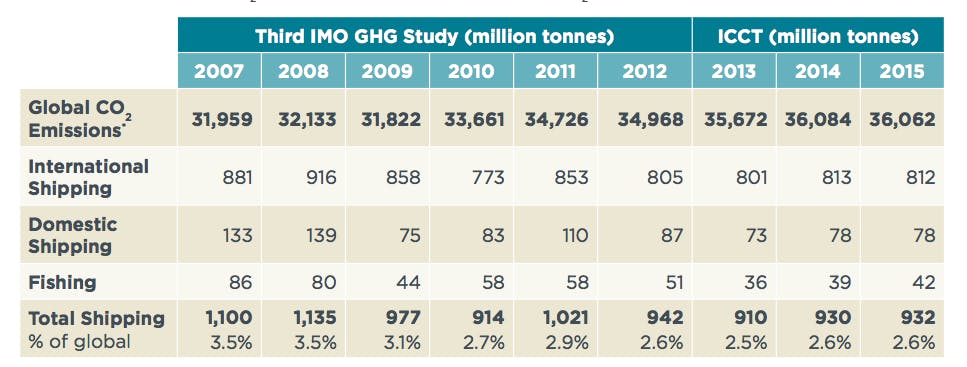

The shipping industry emitted 932 million tonnes of CO2 in 2015, according to a recent report from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). This corresponded to around 2.6 per cent of global energy-related CO2 emissions, up from around 2.2 per cent in 2012.

CO2 emissions from international shipping (millions of tonnes of CO2), in relation to other energy-related sources. Source: ICCT.

While the IMO has adopted some energy-efficiency standards for shipping, emissions are not expected to fall without further efforts, due to the large projected growth in the international shipping industry in the coming decades.

The IMO’s most recent study on international shipping emissions estimated they could grow between 50 per cent and 250 per cent by 2050, under current measures. As other sectors are set to decarbonise, this means shipping could grow to represent an ever larger portion of global emissions if not cap is set.

A 2016 report from University Maritime Advisory Services (UMAS) looked at the amount the shipping industry could emit if it were to stay in line with the Paris targets. It suggested a 33,000MtCO2 cap between 2011 and 2050, for the 2C target, falling to 18,000MtCO2 for 1.5C. This latter figure is around 19 years of current shipping emissions.

Both carbon budgets assume international shipping cuts its emissions at the same rate as the rest of the global economy—implying ambition far in excess of the 50 per cent by 2050 “compromise” currently under discussion.

Another approach would impose shipping emissions cuts in line with comparable sectors, such as transport and industry. This would still require greater ambition than 50 per cent by 2050.

Also being discussed are reductions in line with the emission reduction efforts currently expressed in countries’ nationally-determined climate pledges. However, these pledges fall short of the Paris Agreement’s goals and rely on a ratchet mechanismto increase ambition over time. Several NGOs consider a ratchet mechanism would be problematic for the maritime industry, due to the long lifetime of ships.

Emissions cuts

Much of the debate at the IMO centres on how feasible it is for the shipping industry to decarbonise and how fast it is possible to do so. Last week, a report from the International Transport Forum and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found international shipping could be almost completely decarbonised by 2035, using maximum deployment of known technologies. This is the same target year being pushed at the IMO by the Marshall Islands.

Scenarios in the OECD report foresee future CO2 emissions from shipping falling to 44-156MtCO2 by 2035, a 86-96 per cent cut from the projected 1090MtCO2 in a business-as-usual scenario and up to 95 per cent below current levels.

The report said a combination of different measures would be the most cost-effective way to reduce shipping emissions, including renewable energy and alternative fuels such as advanced biofuels, methanol, ammonia and hydrogen.

A recent report from maritime organisation Lloyds Register and UMAS, setting out the different options for zero emissions vessels by 2030, similarly showed the most suitable technology would be different for different types of ship.

Other technologies which could help cut emissions, include lighter ships, wind and solar assistance, and electric ships for short-distance routes, the OECD report said.

Energy efficiency improvements such as air lubrication and smoother bulbous bow designs are another piece of the puzzle. Finally, operational measures such as reducing travel speed and increasing ship size could achieve further important emission reductions, it said.

Black carbon

Even if a cap or reduction of some kind is adopted at the IMO next week, it is not yet clear whether the final agreement will deal only with CO2 or include other GHGs. Proposals for both are still on the table.

This could be an important point. For example, liquid natural gas (LNG) is often touted as a cleaner option compared to the conventional maritime bunker fuels used in shipping, due to its lower air pollution. Its use is expected rise further in response to an IMO cap on sulphur pollution starting in 2020. But it has also been associated withl arge unintentional methane emissions, which could undermine its lower CO2 emissions if not kept in check.

However, it is actually the relatively short-lived black carbon (BC)—often called soot—which currently makes the second-biggest contribution to shipping’s climate impact, after CO2. According to the ICCT, warming due to black carbon is equivalent to 7 per cent of the sector’s GHG emissions on a 100-year timescale, but 21 per cent on a 20-year time scale. This means reducing black carbon would have a rapid effect on shipping’s contribution to global warming.

Black carbon in the Arctic is of particular concern. As the Arctic melts and new shipping routes open up, cutting travelling distances, there are concerns that black carbon deposits will make snow and ice less reflective, increasing melt from the summer sun and amplifying warming.

The Clean Arctic Alliance, a coalition of 18 NGOs, has been pushing the IMO to ban the use and carriage of heavy fuel oil (HFO) in the Arctic. This is the standard marine fuel for cargo ships, tankers and large cruise ships and a key source of black carbon. The NGOs say an Arctic oil spill could also be harmful and difficult to clean up.

It’s worth noting that there is already a ban on HFO use in the Antarctic. A 2015 report outlined several options for how black carbon from shipping could be reduced.

Ahead of the IMO meeting, a group of eight member states including Norway, Finland, the US, New Zealand and Germany proposed a ban on the use and carriage of HFO in the Arctic by 2021. Canada and the Marshall Islands, however, want more research before supporting a ban. The proposal is also set to be discussed next week.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.