This Chinese New Year, more retailers and suppliers in Singapore and Malaysia might be turning to e-commerce platforms as a source for sea cucumber and fish maw products.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The increase in the online trade volume of these traditional seafood delicacies, widely consumed by households during the festive season but with high conservation value, has prompted wildlife trade watchdog TRAFFIC to issue a warning against driving their harvest and exports to unsustainable levels. The non-governmental organisation (NGO) is pushing for regulators to step up scrutiny and control of such trade.

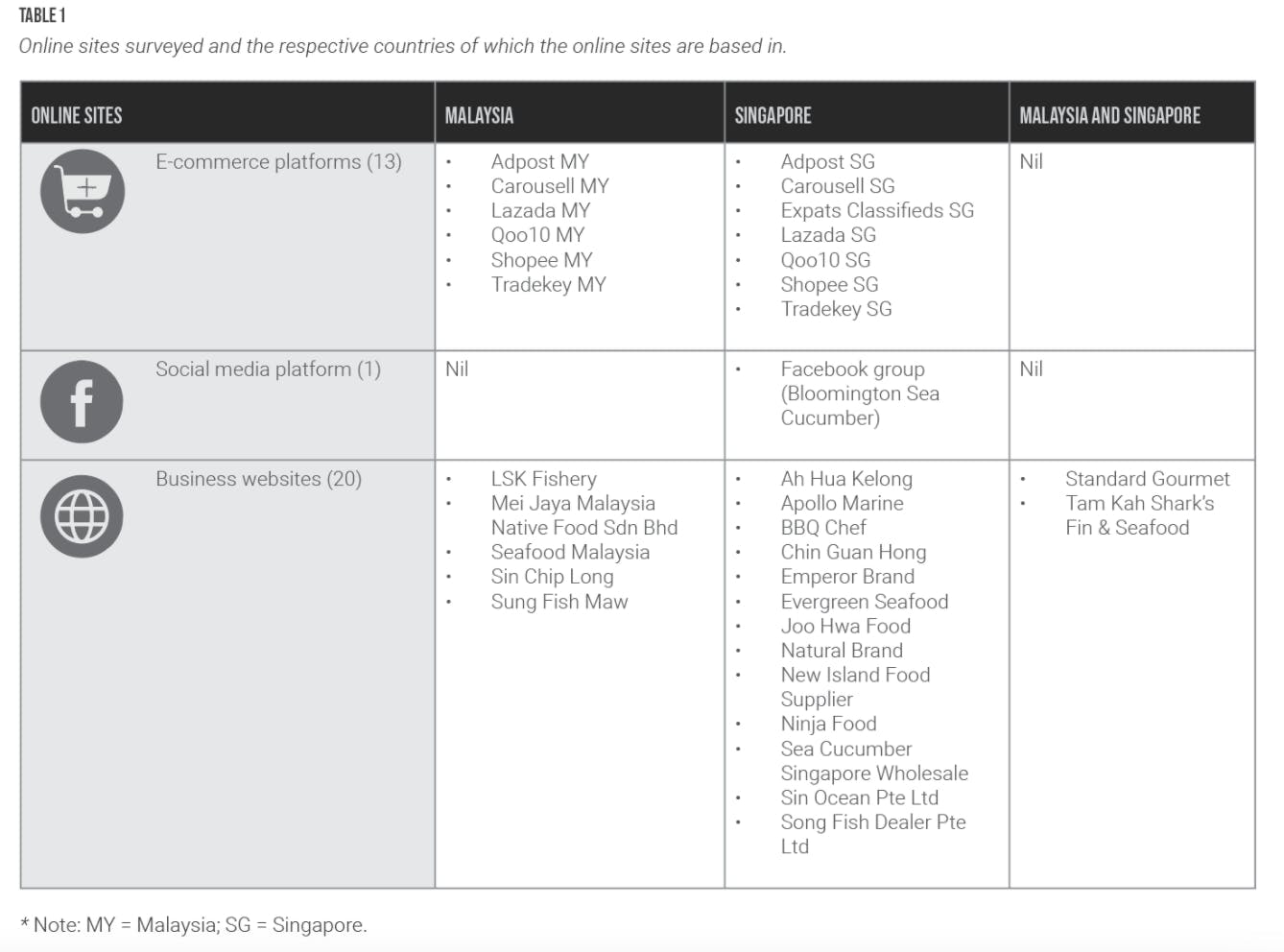

A report released by TRAFFIC today details the high trade volume of sea cucumber and fish maw and their derivative products on popular e-commerce sites in Singapore and Malaysia. From June to July 2020, its research team recorded 339 related advertisements and listings on 33 online sites in the two countries over an 11-day survey period, where the sellers were offering at least 5,547 kilogrammes (kg) of the two marine commodities for sale.

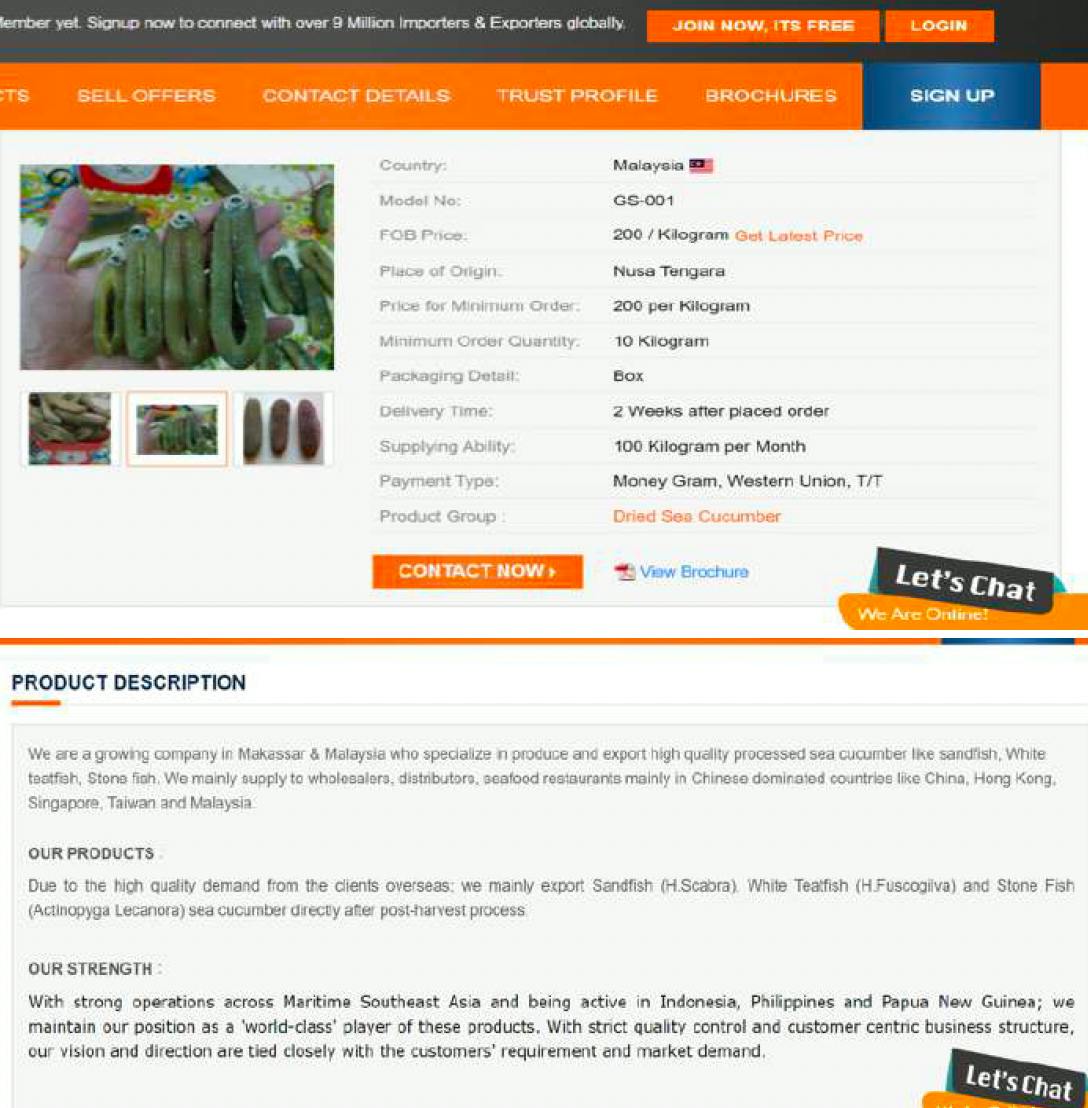

Screenshot of an advertisement on e-commerce platform Tradekey, where the exporter claimed to be able to supply 100 kg of sea cucumber monthly. This includes the white teatfish, or Holothuria fuscogilva, a species protected under CITES. [Click to enlarge] Image: TRAFFIC

A check this month by the researchers confirmed that such trade remains active. TRAFFIC also found three species of sea cucumber, otherwise known as teatfish, that are now regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), being offered on online sites.

The species (Holothuria fuscogilva, Holothuria nobilis and Holothuria whitmaei), which are also protected under Singapore and Malaysian law, and generally vulnerable to overexploitation from commercial fishing, were encountered in 21 advertisements and listings, and offered for US$212.36 per kg on average.

The CITES is an international agreement that ensures that cross-border trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species. The three species of teatfish were officially added to its Appendix II in September 2020.

Kanitha Krishnasamy, director for TRAFFIC in Southeast Asia, said that the organisation’s key concern is with the exceptionally high trade volumes of the commodities, and that it involves many species.

“We are not saying that all trade recorded from this survey is unsustainably sourced. But the fact that there is much that we do not know about, except that legal trade volumes are large, is worrying,” she told Eco-Business. “Once the products enter the supply chain, anyone along that chain could be purchasing it.”

The items offered online in Malaysia and Singapore are also reportedly sourced from more than a dozen countries globally, said Krishnasamy. “The international nature of the trade means that it has a wide environmental footprint.”

Major e-commerce sites under the spotlight for lax monitoring of sellers

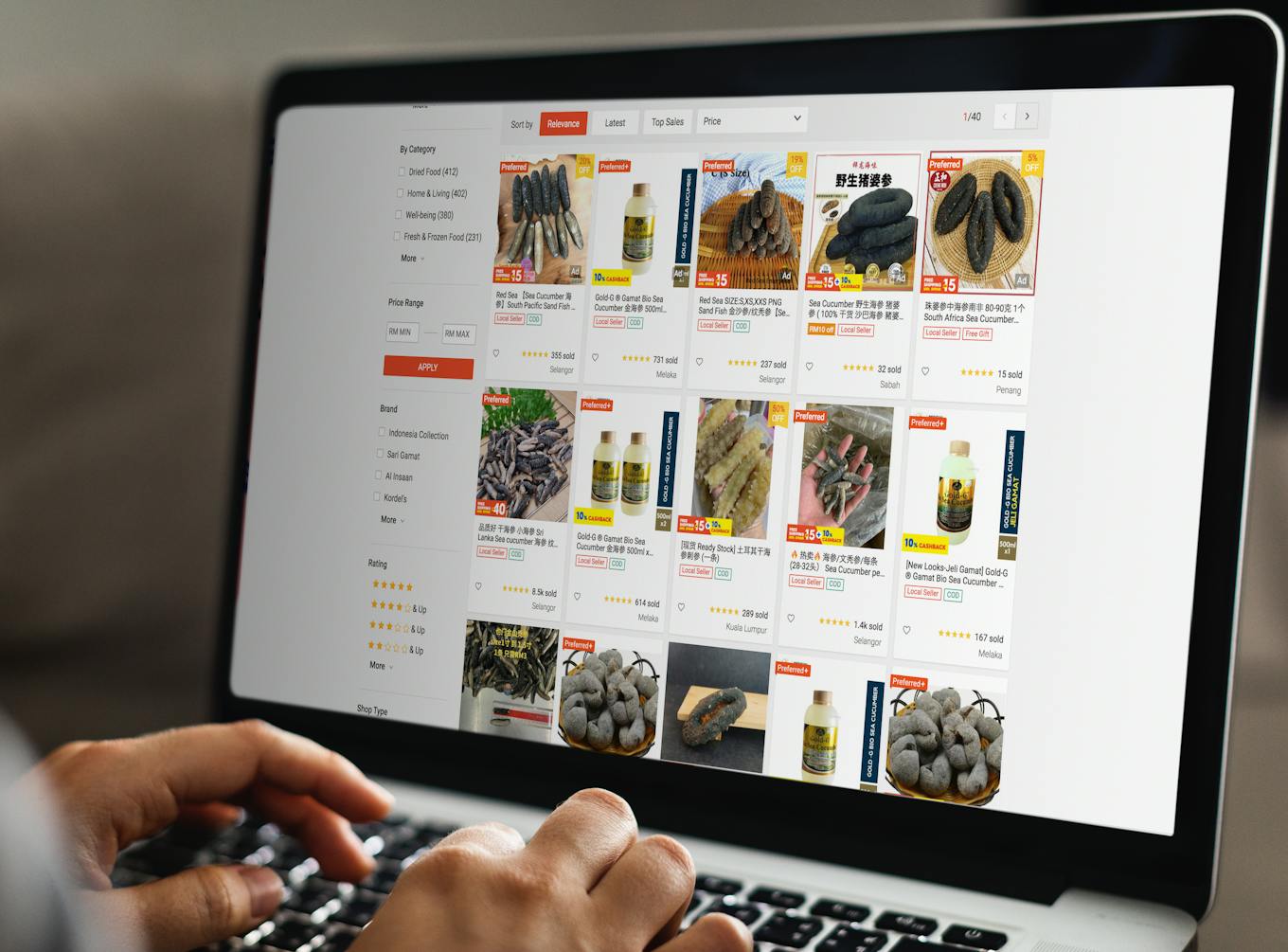

Derivative products of sea cucumbers are offered on an e-commerce site. Image: Ain Bukhri / TRAFFIC

The online platforms that TRAFFIC surveyed included popular regional e-commerce sites such as Adpost, Carousell, Lazada, Qoo10, Shopee and Tradekey, which have presence in both Singapore and Malaysia. Business websites of seafood dealers were also scanned.

On some of these sites, TRAFFIC found listings where online sellers who claimed that they were able to supply large amounts of sea cucumber and fish maw on a monthly basis. This indicated that the actual volume of trade could be much higher than what was recorded during their “rapid assessment”.

For example, TRAFFIC’s report noted that sellers on Tradekey Malaysia and Tradekey Singapore would list their available stock and some claimed that they could supply up to 4,100 kg of sea cucumber or 100 kg to 500 kg of sea cucumber on a monthly basis.

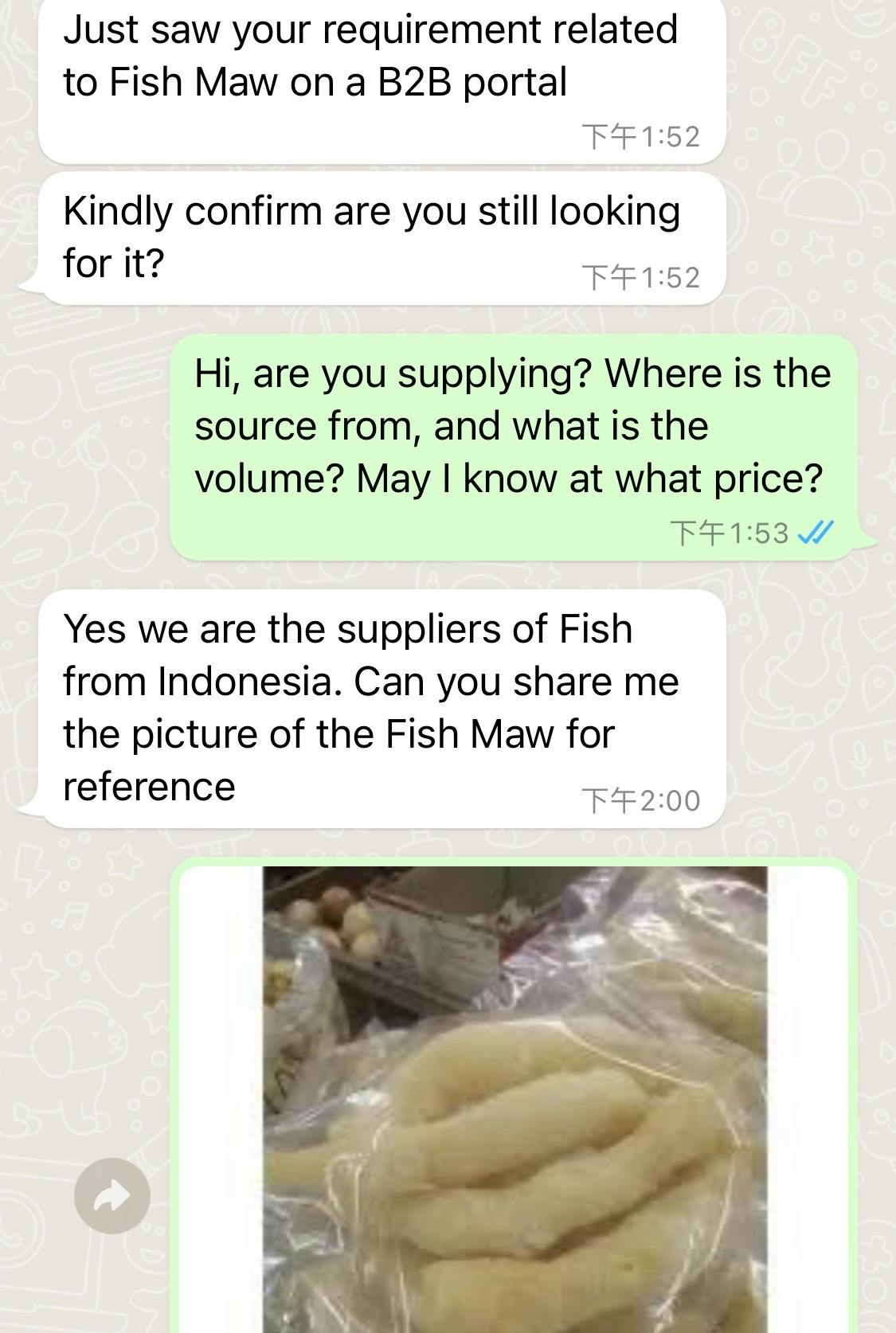

Eco-Business also conducted its own check of the online platforms. On Tradekey, a B2B marketplace headquartered in Karachi, Pakistan, within two hours of registering as a “buyer” on the site – a process which only requires users to key in their direct contact and state what type of products they are looking for – we received five queries from exporters and intermediaries based in Indonesia and Philippines, who claim to be able to fulfil bulk orders at short notice, through messaging platform WhatsApp.

Screenshot of a WhatsApp conversation with a fish maw seller, who claims to be a supplier from Indonesia. Within two hours of registering as a buyer on TradeKey, we received five queries from potential suppliers via direct messaging platforms. Image: Eco-Business

In its user agreement, Tradekey states that user verification is a difficult process and that it cannot and does not confirm the registered company information or personal information of each user. The platform is also “not responsible for whether the conduct of activities are lawful” and “users need to use their common sense to evaluate with whom they are dealing”, said Tradekey in the agreement.

For listings that involved internationally-regulated species, none of the posts mentioned the legal protection status of the species offered, nor a request for any permit, said TRAFFIC in its report.

Eco-Business has reached out to the other e-commerce sites to find out more about their screening processes for sellers. They had not responded to emailed questions regarding TRAFFIC’s findings, at the time of publishing.

TRAFFIC said that current surveys do not allow them to unearth who bulk buyers are, though given the size of the legal trade, these would likely comprise retailers and suppliers, who then sell the commodities to individual consumers or other businesses, in both countries.

“There tends to be more information on sellers than buyers, simply based on how online commerce functions. Some of these conversations are also taking place offline, which researchers have no access to,” said Krishnasamy.

TRAFFIC surveyed the e-commerce platforms and business websites of seafood suppliers over a 11-day period. Image: TRAFFIC

Trafficking that leads to sea cucumber fishery closures

In its recommendations, TRAFFIC hopes that regulators can conduct both online and physical trade monitoring of the sea cucumber and fish maw trade, and introduce a traceability system to verify that only legal and sustainable products are supplied in the market. When goods are seized, authorities should also carry out DNA analysis of the commodities, to identify the range of species involved and ascertain how the trade may impact species.

“Labelling would also help ensure that consumers are fully aware when making purchases”, said TRAFFIC in the report.

This latest report from TRAFFIC also casts a spotlight on sea cucumber and fish maw trafficking activities, which are sometimes under the radar, compared to the trafficking of shark fin, another seafood delicacy consumed across Asia.

For example, high demand for sea cucumber or teatfish, has resulted in over-harvesting in low-depth coastal waters, where the species usually inhabit. Fishermen and skin divers resort to going into deeper areas when this happens. Many countries such as Sri Lanka and Indonesia have reported sea cucumber fishery closures due to its population decline.

“

We are not saying that all trade recorded from this survey is unsustainably sourced. But there is much that we do not know about, except that the legal trade volumes are large.

Kanitha Krishnasamy, director for TRAFFIC in Southeast Asia

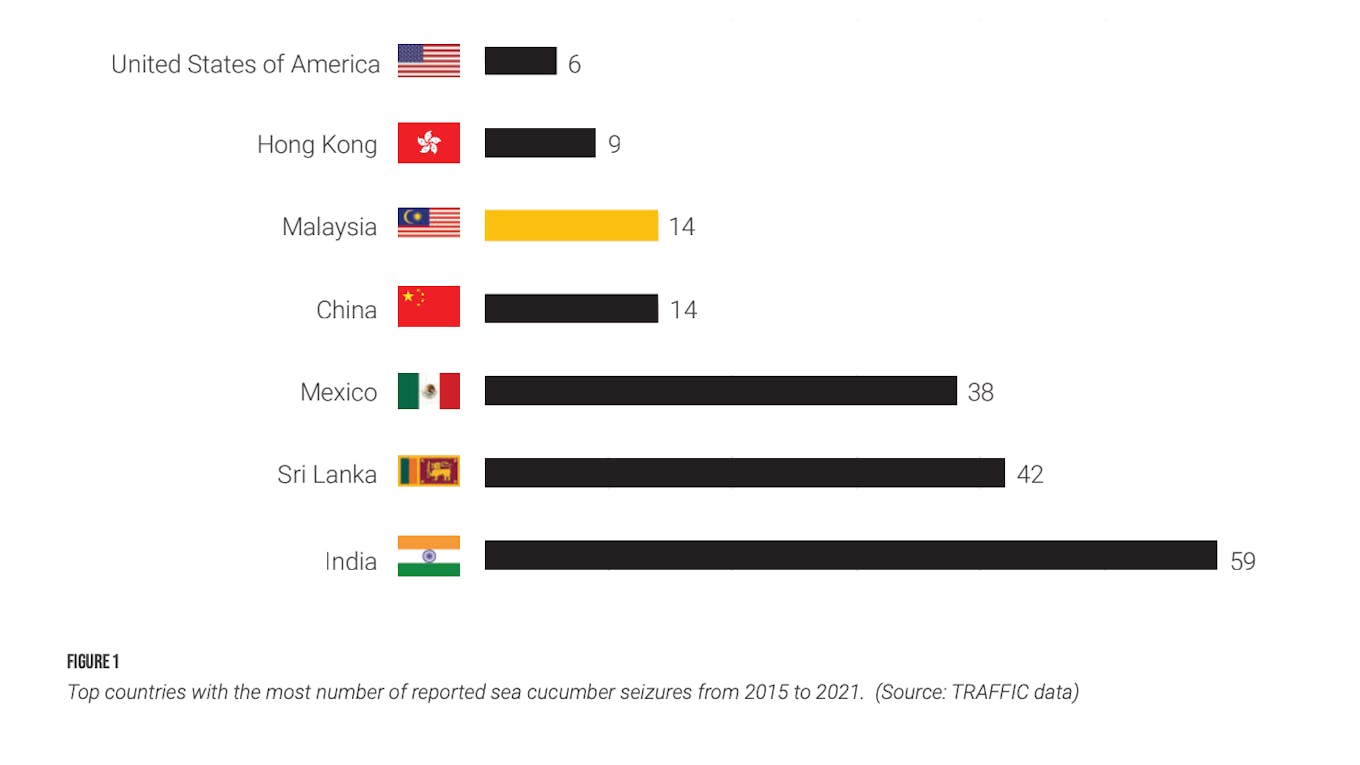

TRAFFIC checked global seizure records and found that from January 2015 to December 2021, at least 92 tonnes of sea cucumbers were seized from 204 incidents, involving 23 countries and territories. Over 80 per cent of these sea cucumbers were seized in 2019 alone. An additional 112,694 pieces of sea cucumber not recorded by weight were also seized, said the report.

Malaysia was among the top five countries with the highest number of reported seizures. There were 14 seizures since 2017 of sea cucumber totaling 6.2 tonnes, with eight seizures in the state of Sabah and five along the eastern coast of Peninsular Malaysia.

Top countries with the most number of reported sea cucumber seizures from 2015 to 2021. Image: TRAFFIC

Last year, Singapore seized illegally imported and re-exported CITES Appendix II-listed teatfish shortly after its listing. The trader was fined S$5000 (US$3700) for the illegal trade.