In recent years, China has disbursed tens of billions of dollars in emergency loans and debt restructuring packages to provide relief for countries around the world at risk of financial crises. The bilaterally-agreed bailouts are often on China’s own terms, but increasingly, the major creditor has been pressed to consider a new proposal that it is finding harder to navigate – debt-for-nature swaps.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Such swaps, emerging as a potential financial tool that will lighten the debt commitments of low- and middle-income economies, essentially see a portion of debt reduced in exchange for resources put towards climate and nature conservation work. In May this year, Ecuador pulled off a record US$1.1 billion debt-for-nature swap to protect its unique Galapagos Islands, sparking off a clamour among other cash-poor but nature-rich countries for such deals.

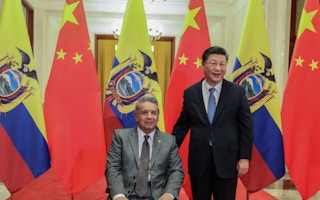

Meanwhile, Ecuador continues to pursue China – its largest bilateral creditor for much of the 21st century – for debt renegotiation built on offers to have portions of its debt cancelled on the condition that funds will be allocated for conservation investments.

China is increasingly seen as an important financier, especially to Asia Pacific nations, which have seen their sovereign debt default risks exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. A recent report published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) pointed to how debt-for-nature swaps could provide relief to Asia-Pacific economies and similarly highlighted China as an emerging but “comparatively less-understood” creditor.

Speaking at the report’s launch event, Kanni Wignaraja, assistant secretary-general and UNDP regional director for Asia and the Pacific, said that while debt-for-nature swaps have yet to achieve the “scale and replicability” required for the financial tool to be impactful, the world has seen how they have been successfully deployed in debt reorganisation packages that have been a lifeline to developing countries caught between low growth and high interest rates.

She said: “(The tool) must be used with other instruments to bring down the cost of debt repayment. It is important for all creditors – bilateral, multilateral and private creditors – to help make up the volume for such deals.”

The UNDP Regional Bureau for Asia Pacific and its China country office recently organised a high-level panel to discuss the potential of debt-for-nature swaps in alleviating the debt burden of developing economies in the region. Image: UNDP

China looks to West-led IMF for debt treatment framework

Since 2020, a new wave of international sovereign debt default risks has surfaced. According to the World Bank, more than 70 low-income nations were collectively managing US$326 billion in debt as of the end of 2021. Research by UNDP identified 52 developing countries with severe debt problems, 12 of which are in Asia Pacific.

Chinese experts, however, are flagging that there are no established practices to navigate debt-for-nature swap negotiations and highlighted the need for “internationally-agreed mechanisms and support systems” to first be in place.

Dr Zhang Wencai, vice president of China Export-Import Bank (Eximbank), said that the concept of debt-for-nature swaps are still relatively new for international financial institutions and more consultations among stakeholders are needed to build consensus. “Rising debt is crowding out investments and technology capital is also inadequate, so we find that the offers are not feasible at the moment. We need a more realistic debt-for-nature swap mechanism.”

Zhang also highlighted how the International Monetary Fund (IMF) should still play an important role to put in place more transparent debt treatment frameworks, and engage more with developing countries.

China Eximbank is currently coming up with debt plans to help Sri Lanka, Zambia and Ghana. Last September, it was also involved in a deal with Ecuador to restructure the country’s debts worth about US$1.8 billion, by extending the loans’ maturity.

‘Flexible approach’ sought

Instead of debt-for-nature swaps, China is instead leaning into “pause clauses” or what are known as climate resilient debt clauses (CRDCs) to provide borrowing countries with more time to repay their debts. Under such a mechanism, a deferral is triggered in the event of a pre-defined natural disaster leading to major financial losses; repayments are suspended on a cost-neutral basis, with additional interest payments usually still applicable under the deferral.

In June this year, the World Bank also agreed to allowing countries hit by disasters to pause repayments on loans, after a campaign led by Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley for a new global pact to help poor and climate-vulnerable countries tackle their debt crises and allow them the fiscal space to rebuild.

Zhang said CRDCs are a solution that China is exploring, and acknowledged the important role that China can play as a major creditor. “Creditors and debtors should be encouraged to discuss terms in a flexible way.”

Speaking at the UNDP panel, Mariyam Manarath Muneer, deputy minister of finance for the Maldives also highlighted how debt-for-nature swaps are inherently complex. “The transactions take time, and require strong commitment from the debtor country,” she said.

In 2020, Maldives, only gradually limping back to normalcy after Covid-19 but still neck-deep in Chinese debt, tried to work out a debt-for-nature swap which did not materialise. Muneer said that the experiment was an important lesson, as it reminded the government that there are multiple factors to consider before jumping into such a deal.

“For example, an analysis must be done to fully price the transaction from both the social and environmental standpoints. On our island archipelago, it means (the needs of) fishery and tourism stakeholders need to be accounted for too,” she said, adding that a “fixed international cooperation framework” is needed for debt swaps to work.

Dr Palitha Kohona, ambassador of Sri Lanka to China, said that even if it is not through debt-for-nature swaps, China needs to recognise that it plays a critical role as a global lender and in difficult circumstances, should help sovereign borrowers restructure repayments.

It would be good if China can “continue its generosity into the future”, she said. “It makes a difference for struggling economies.”

Want more China ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business China newsletter here.