Supermarket shelves were emptied across the eastern states of the United States earlier in January as residents rushed to stock their homes with daily items and braced for the unusually cold weather.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Images of cities buried in snow and buffeted by strong winds were on the front pages of newspapers around the world, as a severe cold snap saw temperatures in cities such as New York falling to -20°C and wind gusts reaching some 72 kilometres per hour.

The increased frequency of such cold snaps in recent months have also affected parts of the United Kingdom and northern Asia such as Japan and South Korea due to disruptions to the jet stream that regulates weather over the Northern Hemisphere, according to meteorologists.

Meanwhile, 2015 was officially declared the hottest year in history, with Western Australia experiencing its worst heatwave in decades and California in the US suffering one of the worst droughts.

The weather has preoccupied mankind for centuries, but its increasingly erratic and extreme behaviour—which could have been exacerbated by climate change—has been posing an increasing challenge to governments all over the world.

In recognition of these risks to national security, public officials are increasingly paying attention to climate adaptation.

This involves putting in place strategies to cope with climate changes in their country before the costs—both economic and environmental—becomes exceedingly high.

In Asia, for example, scientists from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlighted in a 2014 report that some key climate risks for the region included urban and coastal flooding, and water and food security.

A look at adaptation

Humans have been adapting to the changing weather for centuries. In recent decades, scientists, designers and planners have made significant progress in dealing with weather-related disasters such as droughts and floods.

Australia, for instance, overhauled its water management system after weathering a 12-year drought from 1997 to 2009. It launched a successful campaign around water conservation that encouraged long-term planning and helped to change behaviour among residents in how they consumed water.

To combat heatwaves—which has also become more frequent in the country—the government has also invested into studies on the effects of heat on its population and a heat health alert system. This notifies local governments, hospitals and major metropolitan health and community service providers of forecasted extreme heat and heatwave conditions which are likely to impact human health.

Jane Mullett and Darryn McEvoy from the Climate Change Adaptation Program at RMIT University, in an essay for The Conversation, noted that since the 2009 heatwave—in which there were 374 deaths attributed to heat and 173 lives lost to bushfires in Melbourne—a lot of effort has gone into understanding what happened and why.

“Changes have been made to emergency management procedures and local councils have designed new heatwave plans… Heatwave plans are now part of normal local council business.

“The police in Victoria are now up to speed with South Australia and designated to manage any heatwave emergency, whereas pre-2009 there was no command level set for heatwaves,” they noted.

In New York, city leaders have also launched ambitious initiatives to reduce the city’s vulnerability to coastal flooding and storm surges by improving existing infrastructure as well as researching and building floodwalls and putting up other coastal flood protectors.

This came in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, which hit the city hard in 2012 and caused US$19 billion in damages and economic losses. It shone a global spotlight on the importance of building climate resilience—defined as the ability of a city to survive and adapt despite any chronic stresses or shocks.

In the UK, the government has also published a plan called Thames Estuary 2100 which sets out recommendations for flood risk management for its capital London and the Thames estuary through to the end of the century.

It is “the first major flood risk project in the UK to have put climate change adaptation at its core”, said David Wardle, executive manager of the Thames Estuary Programme. This is seen as necessary, as the UK must “either invest more in sustainable approaches to flood and coastal management or learn to live with increased flooding”, said the report.

Singapore’s geographical location shields it from extreme weather events such as typhoons, but this does not mean it is free from vulnerabilities.

As a low-lying small island state, it is at risk of climate change impacts such as rising sea levels, coastal and urban flooding, and hotter temperatures.

Singapore’s efforts

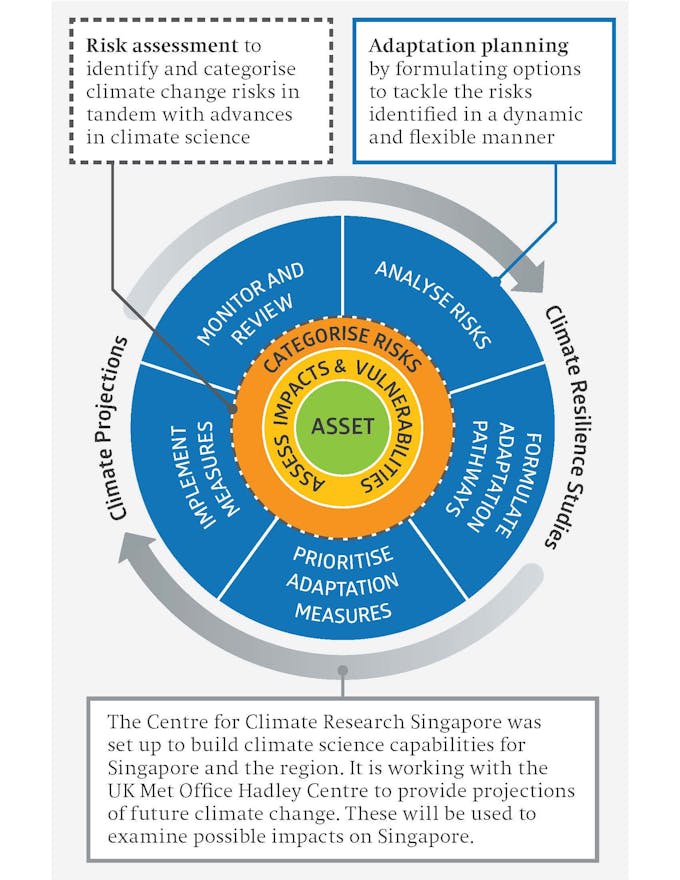

Image: Resilience Working Group, Singapore

The Singapore Government has, since 2010, set up a multi-agency Resilience Working Group (RWG), under the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Climate Change, to study Singapore’s vulnerability to climate change and recommend long-term plans that ensure the nation’s adaptation to future environmental changes.

The working group has identified key risks such as sea level rise, temperature increase, and rainfall and wind changes as possible impacts that may affect Singapore in the future.

Furthermore, it has also developed a Resilience Framework that is used to assess Singapore’s physical vulnerabilities to climate change and to guide the formulation of adaptation plans to protect the country against potential climate change impacts up to 2100.

In a study by the Meteorological Service Singapore’s Centre for Climate Research Singapore, scientists found that by the end of the century, unusually warm temperatures could become the norm in the future. Singapore’s mean temperature could increase by 4.6°C by then, if no efforts are made to mitigate climate change.

The frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall events in Singapore are also set to increase as the world warms. The contrast between the wet months and dry months is projected to become more pronounced. Singapore may also see a mean sea level rise of up to 0.76m by 2100.

To protect itself from these impacts of climate change, Singapore has already implemented several adaptation measures.

For example, the minimum reclamation level for newly reclaimed lands was raised from 3m to 4m above the mean sea level since 2011. The Land Transport Authority also recently raised a stretch of road along the coast, Changi Coast Road and Nicoll Drive, in anticipation of rising sea levels.

To mitigate flood risk, the national water agency PUB has also been enhancing drainage infrastructure and stormwater management systems while also ensuring that the country has adequate water supply in case of droughts.

“As we put in place our plans, we will ensure that these do not overly constrain what can be done in future”, said an official from the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources.

Adaptation measures indeed require time to implement and have to be taken early. But at the same time, these plans must be designed in such a way that they can be adjusted to respond to new climate data and science.

“This is the core of Singapore’s long-term proactive approach to climate change adaptation,” said the ministry.

This article was first published on the NCCS website. Subscribe to their newsletter here or follow them on their Facebook page.