A growing number of people are becoming overwhelmed by the fear of irreversible environmental damage and ecological disaster. Those in the global south on the frontline of some of the most erratic weather patterns attributed to climate change, could be particularly vulnerable.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Changing climate can affect mental health and manifest in the form of aggression, trauma, substance abuse, or depression, reports the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Three in four Singaporeans expect the climate breakdown to impact the availability of basic resources and their economy in the next 30 years, yet almost two-thirds feel like they cannot take any meaningful action on climate change, according to Climate Conversations, a non-profit that facilitates networks for climate action.

Many have stood up in recent years to share their anxieties about a perceived “ecological doomsday”. One of them is Aidan Mock, 26, a youth climate activist who has grappled with climate anxiety firsthand.

“Eco-anxiety for me is very deep concern that we will not be able to reverse the climate crisis in time. On a more personal level, it’s the feeling of not being able to contribute enough to this cause as individuals,” he said.

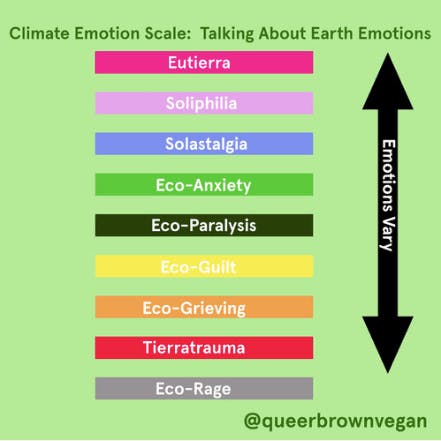

The Emotional Climate Scale

While the concept of climate anxiety is still in its infancy, environmental educators like blogger Isaias Hernandez, have started to popularise a new-age lexicon to help legitimise the increasing complexity and range of emotions one might feel in response to the climate crisis.

Glenn Albrecht, an environmental philosopher and professor of sustainability from the University of Murdoch in Australia, coined the terms associated with psychoterratic states — emotions that people feel in relation to the earth.

Albrecht notes that “people appear apathetic and disengaged with reality as it unfolds, but their detachment might be eco-paralysis rather than apathy or avoidance.” Eco-paralysis describes one’s inability to respond to the climate crisis.

Xinying Tok, co-founder and director of Singapore-based Climate Conversations, believes that there is a fine, but crucial, line between these behaviours.

“There are several reasons why individuals might choose not to act while acknowledging the climate breakdown and its impacts. I’ve met some who feel a heavy mental burden from climate change and other social issues, or cannot feel the impact of individual actions,” she said. “On the other hand, I’ve also met individuals where inaction is more a form of deflection from knowing how difficult some of the necessary changes are.”

Climate Conversations invites people into their community or other climate groups so they can find support from other like-minded people. “No matter where your starting point is, when you see others not giving up just because things are difficult, it helps,” Tok explained.

Mock warned that eco-anxiety has the potential to divide the movement if not managed properly. “I think eco-anxiety could harm interpersonal relationships when we feel that other people aren’t doing enough or don’t share the same views as us. There is a chance for us to get judgemental, wondering why others aren’t doing as much as us,” he said.

Another big risk is burnout, which is a rising phenomenon in the environmental activism scene. “We need to find some way of being useful to the world while being able to protect ourselves, because burnout is such a big thing in our line of work,” said Sammie Ng, co-founder of Speak for Climate, a ground-up initiative that looks to encourage greater public participation in climate policies.

Explaining inaction

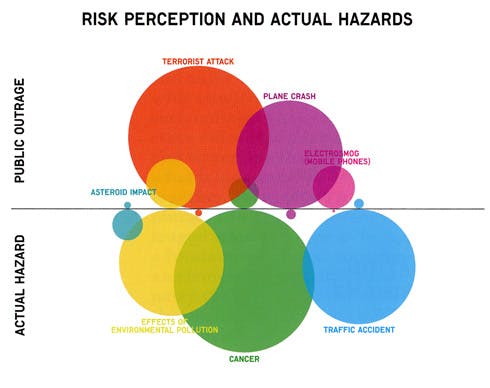

Human psychological tendencies to risk perception relative to the danger of actual hazards. Plane crashes and asteroid impacts receive disproportionate amounts of public outrage, while the actual hazard of environmental pollution is not regarded enough. Image: Risk Academy.

A lack of climate action channels, rather than a lack of awareness may be part of the problem. In fact, “too much awareness and too few avenues may be debilitating,” said Denise Dillon, an environmental psychologist from James Cook University, Singapore.

“It can be overwhelming to think of it in this age of information overload. The more information streams in, the more you feel like you don’t know enough, or that you think you’re never going to be able to resolve this massive problem. That might put some of us into a kind of despair, in which case some might not even try,” said Dillon.

Dillon believes that eco-paralysis is often an amalgamation of causes stemming from the dragons of inaction — the psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation.

In a recent podcast with Eco-Business, she discussed why humans are so bad at thinking about climate change. “We’ve evolved to respond to clear and immediate danger, which is why people are more worried about in-your-face terrorist attacks than climate change.”

The Finite Pool of Worry, according to Dillon, also explains that when humans become more worried about more apparent threats, we may edge out others. At the moment the Covid-19 takes precedence, but worries can spill over and result in cumulative anxiety.

“There is a big proportion of people who have so much on their own plates that it would be so difficult for them to absorb any other information or to take on anything more,” said Ng. “We don’t really see that unless we have families to take care of, or if we live in safe Singapore, but I think those are very real concerns that we should take into account.”

Climate activists also need to accept the long-term nature of their battle. “We tend to want to see immediate results and very direct key performance indicators, but patience is a big part of climate action because political and social changes can take many years to happen — sometimes even past our lifetimes,” Ng said.

What do we do about it?

Tok stressed that people prioritise the social causes they value differently, but that their facilitators’ key goal is helping people see that “no matter what issue they care about, climate change impacts all of that.”

Individual action, as it turns out, may be a matter of personal preference. “Some environmental advocates would say that focusing on recycling can be very debilitating, especially when you learn that it does very little change,” said Tok. “Others say that it is something that they do every day to remind them of what environmental protection means, which can be an important part of the journey too.”

Clinical psychologists have drawn attention to the impact of the climate crisis on people’s wellbeing, with experts from the psychological profession rallying around these issues to form groups to help people move from paralysis to action. The validation of emotions is a key first step.

“A lot of these emotions are being systematically stigmatised because of the tone policing in our world. We are taught to keep the anger to ourselves, and if we show it publicly, that is seen as violent,” Ng said. “We should instead be finding ways to channel this anger positively.”

A feeling of helplessness might be an indication that it is time for one to collaborate with others. “For me, the answer is always to take action such that the impacts are at a larger scale than just the individual level,” said Mock, who helped organise Singapore’s first climate rally in 2019. “Whether it’s bringing friends along for beach cleanups or lobbying for institutional and systemic policy changes, it was about finding places where I felt that I was contributing positively.”

With the destigmatisation of mental health, forming communities of support within the activism circle has become increasingly celebrated. Some draw inspiration from the likes of Buddhist activist Thích Nhất Hạnh and eco-philosopher Joanna Macy, and are making it a habit to celebrate good news and small wins.

“I think it’s always better to tell the story of hope, and opportunities and things that we can do to make things better. That also gives folks the opportunity to insert themselves into the narrative,” Mock said.