Calls to tax the ultra-rich are not new, but a group of economists have quantified how much the wealthy should be taxed to help finance a global climate fund and close the world’s climate finance gap.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

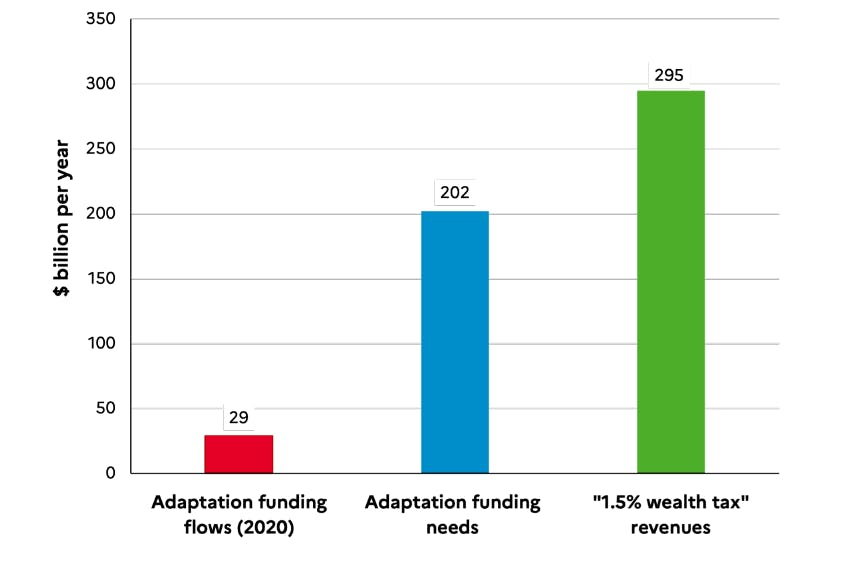

Calling it the “1.5 per cent for 1.5 degree” wealth tax, a study by the World Inequality Lab, co-directed by renowned economist Thomas Piketty, said that a “relatively modest” tax on centimillionaires – individuals owning over US$100 million – could raise about US$295 billion per year, which is “more than enough to fill the current adaptation gap”. Under the Paris Agreement, 195 nations have agreed to work towards limiting global warming “preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius” above pre-industrial levels.

The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that up to US$340 billion is needed annually to meet adaptation needs in developing countries by 2030. Currently, international adaptation finance flows to developing countries are about 5 to 10 times below estimated needs – not including costs of loss and damage.

Closing this climate finance gap has featured high on the agenda in many international meetings, including at COP27 last year, where wealthy nations finally signed off a loss and damage fund that would compensate developing countries hit hardest by the climate crisis.

Adaptation funding needs in developing countries compared to revenues that could be raised from a global wealth tax on centimillionaires. Image: World Inequality Database

The tax that the economists are proposing would apply to the 65,000 richest individuals in the world, or roughly 0.001 per cent of the global adult population. This means that the proposed global climate fund would be created at no cost to 99.999 per cent of the world’s population, said the authors of the Climate Inequality Report 2023.

The tax would range from a rate of 1.5 per cent on assets owned between US$100 million and US$1 billion, to 3 per cent for assets above US$100 billion. Individuals who would be taxed in the latter range are mostly tech moguls based in the United States, like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Twitter CEO Elon Musk, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg.

The authors added that low- and middle-income countries should also consider taxing centimillionaires living in their jurisdictions. Their study found that even as the Global North contributes the bulk of the world’s carbon emissions, the wealthiest – the top 10 per cent of income earners – living in other countries are guilty of driving up emissions too. “Nowhere in the world do the emissions of the top 10 per cent meet the Paris targets, although there are marked differences across regions,” said the report.

Asia should tax the wealthy too

In the context of Asia, home to a growing number of centimillionaires, the tax proposal is estimated to raise US$71 billion in East Asia and US$20 billion in South and Southeast Asia.

The authors acknowledged that “it is unlikely that a global deal on a tax on extreme wealth to fund climate change adaptation and mitigation will be obtained in the very near future”. But the study suggests that the proposed wealth tax “can be initiated by a subset of countries without the need for consensus” at the COP climate negotiations.

Behind this targeted financing mechanism lies the idea of reversing the increasing global carbon inequalities while unlocking climate finance for developing countries.

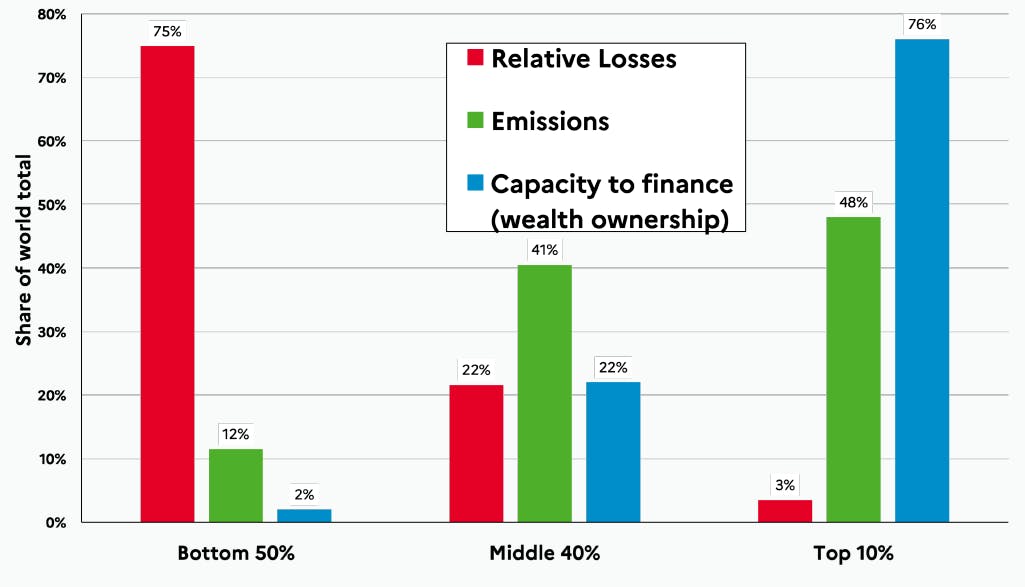

“Global carbon inequality” shown through a comparison of the global bottom 50 per cent, middle 40 per cent, and top 10 per cent in terms of relative losses, emissions, and capacity to finance. Image: World Inequality Database

This “global carbon inequality” is characterised by the Global South – especially the low-income populations within these countries – bearing the highest proportion of income losses due to climate hazards like exposure to serious flooding, despite contributing the lowest share global emissions and having the lowest capacity to finance climate mitigation and funding efforts, compared to the wealthier nations.

“The main conclusion here is that,” the authors said, commenting on their proposal, “given the extreme levels of wealth concentration in the world today, even modest tax rates on top wealth holders can yield substantial tax revenues.”

Apart from the progressive wealth tax, the report suggests that other well-designed climate policies focusing on distributional impacts, like the removal of fossil fuel subsidies and targeted cash transfers, can reduce climate change inequalities as well.

The study cites Indonesia’s efforts to phase out fossil fuel subsidies as a successful example that proves “potential fuel price hikes do not necessarily result in welfare losses for the poor”. This phase-out over the past decade has been accompanied by assistance to low-income households and a redirection of savings from the subsidy reform into other social programmes and infrastructure.

However, despite managing to reduce fossil fuel subsidies from US$13.6 billion in 2014 to US$1.6 billion in its 2015 state budget, Indonesia still has the second highest level of total subsidies for fossil fuels among G20 countries, according to a report by Climate Transparency last year.