Little is known about the potential harm that deep-sea mining could do to marine ecosystems, but there is one impact of ocean extraction that scientists believe could devastate bottom-dwelling marine life — noise.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Without light to help them navigate the ocean depths, deep-sea creatures commonly use sound to find their way around. A study published in the journal Science in July finds that noise from a single seabed mine could travel 500 kilometres — approximately twice the distance from Singapore to Malacca — in light conditions, potentially wrecking the sonic environment for benthic life forms.

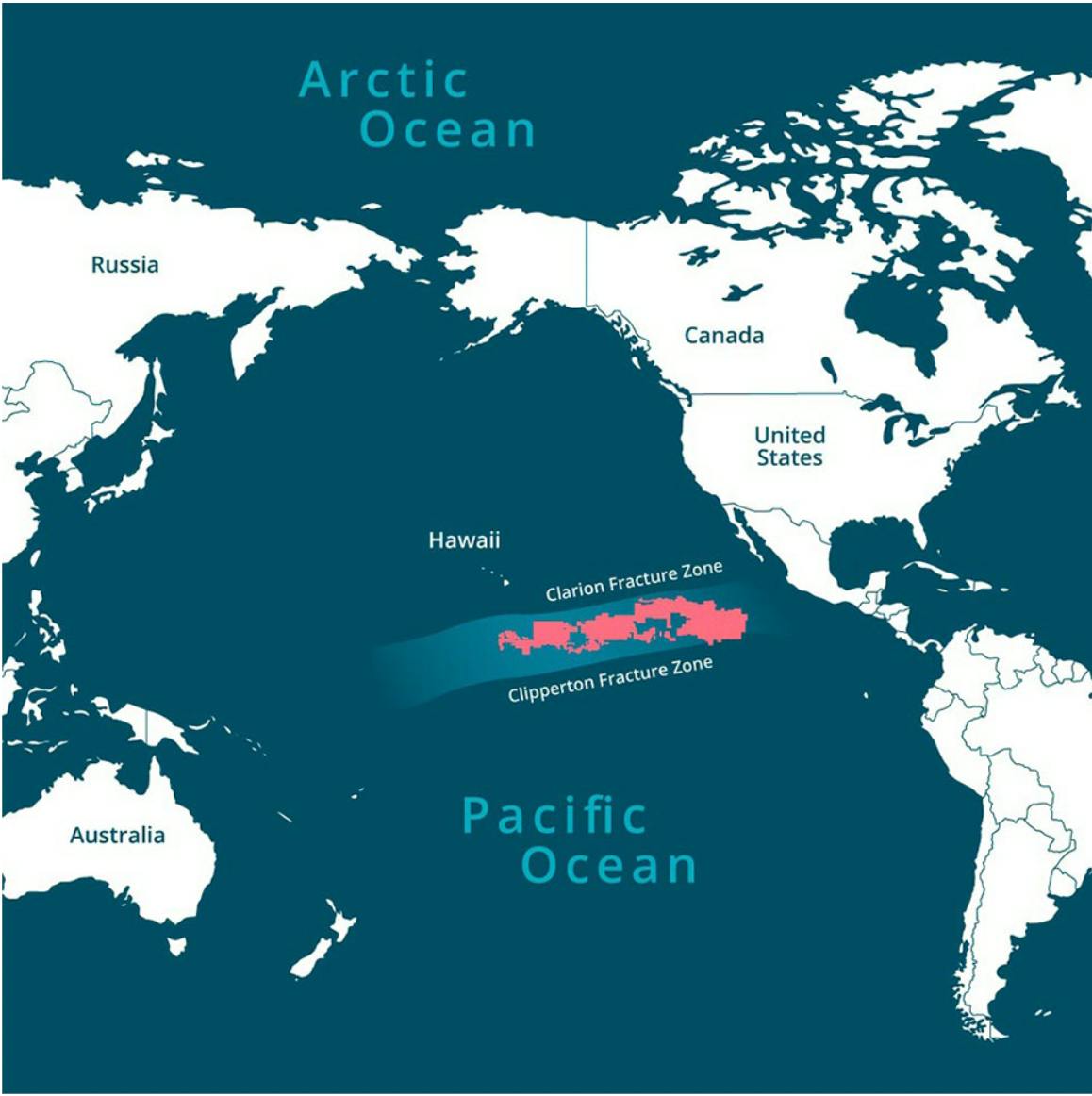

Among the animals that use sound to feed, communicate and navigate are Beaked whales, which have been known to swim to depths of 5,000 metres. A 2015 study found that these deep-water whales may frequent an area of the Pacific Ocean earmarked for industrial-scale mining known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

Seventeen contractors are readying mining operations for the CCZ, and could proceed as soon as July 2023, once regulations are approved by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and the seafloor is opened up for commercial-scale exploitation for the first time. If each of the contractors launched a single mine, 5.5 million square kilometres — an area bigger than the European Union — could be disrupted by noise pollution, the study predicted.

The research was conducted by marine wildlife conservation group Oceans Initiative, Australia’s Curtin University, the University of Hawaii and the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Japan. It was funded by United States-based non-governmental organisation The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Due to a lack of available data on underwater noise pollution from mining companies’ trials in the CCZ, researchers used noise data from oil and gas industry ships and coastal dredges as a proxy. The researchers said noise from deep-sea mining operations is likely to be more severe, because seabed mining equipment is larger and more powerful than the proxies.

The Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone, where industrial-scale seabed mining is slated to go ahead in a year’s time. Image: Horizon, CC BY 4.0

Craig Smith, a professor at Hawaii University, said the research findings suggest a rethink of mining regulations is needed. “Our modelling suggests that mining noise could impact areas far beyond the actual mining sites, including preservation reference zones (PRZs), which are required under draft mining regulations to be unaffected by mining,” he told Science Daily.

The level of noise pollution from mining the seabed should lead to a tightening of the number of mining operations permitted in the CCZ, he said.

Contractors are obliged to monitor the areas outside their mining operations, known as PRZs, as well as the areas that are directly impacted by mining, called Impact Reference Zones (IRZs). Observers say there is no clear guidance from ISA on how PRZs should be designed, including which habitats they include, how big they should be, and the factors that should be considered when monitoring them.

A year ago, the Pacific island of Nauru triggered a rule with the ISA that requires the regulator to allow seabed mining in two years’ time, regardless of whether regulations have been finalised.

Nauru’s push to green-light industrial-scale deep-sea is supported by nations including Japan, China, Belgium, United States, United Kingdom, Russia, Australia and South Korea. Last week, Singapore affirmed its support for deep-sea mining despite making a series of pledges to protect the ocean the week before at a United Nations event.

Ocean mining, say its protractors, is necessary to power the energy transition, as the seabed is littered with trillions of valuable rocky nodules containing manganese, copper, cobalt and rare earth elements, which could be used to make wind turbines, solar panels and electric car batteries.

Environmentalists and a growing number of scientists and governments say that not enough is known about the impact of deep-sea mining on ocean habitats for large-scale exploitation to go ahead. Scientists have warned that extraction would compound ocean stressors, including climate change, bottom trawling and pollution, and obliterate ecosystems about which less is known than the surface of the moon.