The largest protein markets in Asia need to massively scale up their adoption of novel meat substitutes in the coming decades to meet the region’s climate goals, according to a study by Asia Research and Engagement (ARE).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

China, the world’s top food consumer, needs alternative proteins to comprise 50 per cent of its protein intake by 2060 to have a credible trajectory towards eliminating food emissions. The figure rises to at least 85 per cent for fast-growing India and Pakistan, though traditional plant protein could play a bigger role in these countries.

“Ambitious” measures in stopping deforestation and reducing industrial meat production are still necessary, but these existing efforts by themselves are not enough to rein in climate change, the Singapore-based consultancy said.

The report adds to calls for businesses and governments to help replace traditional meat products with new plant, microbe and cell-based alternatives, which have lower carbon emissions but are not widely consumed. Livestock accounts for about half of global food emissions, and a sixth of total manmade greenhouse gases.

“Promoting alternative proteins and reducing meat consumption are vital to Asia’s climate and protein security,” the study said.

Balancing the numbers

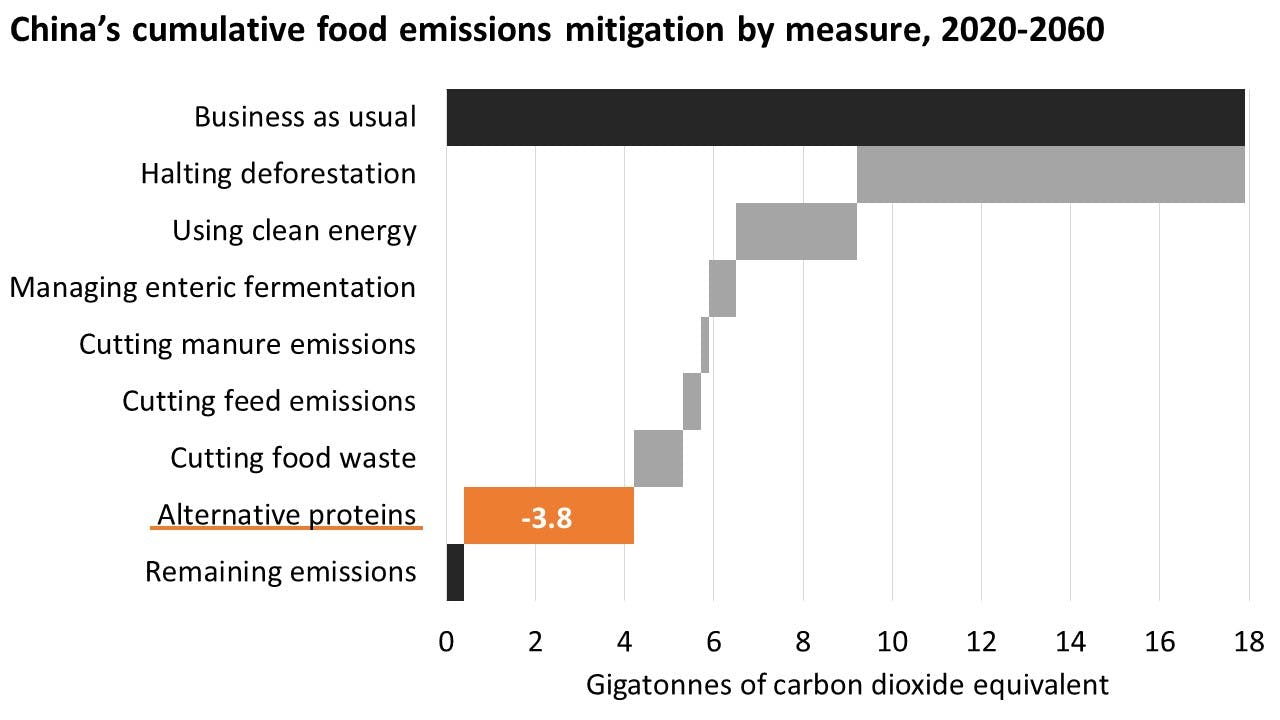

ARE researchers found, through modelling work, that China could pursue stringent sustainability efforts and still have its food emissions exceed a “climate-safe” level by a cumulative 4.3 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide from now till 2060 – also the year by which the country has pledged to reach net-zero.

The safe level would have required China’s protein emissions to drop 72 per cent to 0.2 gigatonnes by 2060, referencing a benchmark set by climate nonprofit Science Based Targets initiative.

Even if China ends deforestation by 2030, fully switches to clean energy by 2055 and makes steep cuts in food waste and livestock emissions, the country’s 2060 food emissions would still be hovering close to 0.4 gigatonnes, twice the safe level.

Emissions are propped up by increasing protein demand from China’s growing middle class. A shrinking population in later decades, as China ages, does not serve as a complete counterbalance.

Cumulative emissions mitigation by measure, China, 2020-2060, under a “Protein Transition” scenario modelled by Asia Research & Engagement. Data: Asia Research & Engagement.

That leaves replacing industrially produced meat with alternative proteins to cancel out most of the excess emissions, an effort that will need about US$730 billion in capital expenditure up until 2060. Industrial meat production should peak by 2030 and fall rapidly thereafter, the ARE report said.

Intensive livestock farming in China creates large amounts of manure and environmental pollution, the study noted, adding that Chinese importers with limited deforestation pledges have been importing large volumes of Brazilian soy as animal feedstock, potentially causing deforestation overseas.

Recent studies have shown that alternative proteins have significantly lower climate change impacts than conventional meat, with the additional energy expenditure from producing food in specialised factories far compensated for by the smaller land and raw material footprint.

China’s latest “Five-Year Plan”, the country’s top directive for national development up until 2025, for the first time called for research into lab-grown meat and plant-based foodstuffs. Globally, plant-based proteins have gained some momentum, but only Singapore and the United States have approved lab-grown meat products for sale.

ARE said Asia’s nine next-largest protein markets follow a similar trend in requiring alternative proteins to meet decarbonisation targets. For instance, highly-developed Japan will need novel substitutes to make up 45 per cent of its protein volume by 2060 in order to decarbonise. Rapidly growing Indonesia needs 60 per cent, while Thailand needs 30 per cent.

India and Pakistan, where growth in wealth and population are expected to significantly increase demand for meat and dairy, will need to find replacements for 85 and 90 per cent of its protein intake by 2060 respectively, the study said. However, some of the replacement may be through traditional plant proteins such as soy and beans – not the more processed variants made to look like meat patties.

Kate Blaszak, director of protein transition at ARE, said the conventional plant products were included because India and Pakistan are lower-income countries, and people are eating less meat and seafood.

But simple plant proteins may not be popular with the growing middle class across Asia, even though such products may be more sustainable than novel foodstuffs.

Affluent consumers will still want meat, or at least similar-looking and tasting products, Blaszak explained.

“There is a real status still attached to meat, to animal proteins,” Blaszak said.

Support needed

But alternative proteins have been facing headwinds. While investments into research and new start-ups have been growing healthily in Asia, the more mature markets in the west have seen notable slowdowns, on the back of sluggish sales.

Consumers have complained that the meat substitutes are not as tasty as actual meat. And they are concerned with the often complex ingredient list of alternative proteins.

Blaszak said alternative protein development in Asia has taken a more “slow and steady approach”, and that consumer surveys have shown good results for products like cultivated meat and seafood.

The ARE report said governments may need to re-orientate subsidies from intensifying animal production to alternative proteins to accelerate the switch to sustainable substitutes.

The study also noted that few banks actively promote the switch to alternative proteins via their investments. But Asia companies are already starting to build their novel foods portfolios, ARE noted.

“If market forces fail to set a more aggressive pace, policies and regulations may be needed to accelerate the shift. This is already happening in the European Union. Banks, corporations and shareholders that anticipate these regulatory changes by promoting the transition before they are imposed stand to gain first-mover advantage,” the study said.

Blaszak added that other measures, such as peaking industrial meat production by 2030, are also important.

“If that continues in a business-as-usual way, it will just blow the whole [climate effort] out of the sky,” she said.