A resort built in the middle of extraordinarily-shaped hills located on the island of Bohol in the Philippines seems like an ideal getaway for tourists in the summer season. Or at least that must have been what a Filipino content creator thought while posting a video promoting the destination on his social media platform.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Yet within two weeks of publication, the feature went viral, as hundreds of thousands of netizens registered their outrage and displeasure at how the structures had encroached on a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a natural wonder in the archipelago.

The Chocolate Hills, with its uniformly-shaped conical isolated mounds that take on a golden-brown colour in summer, are considered Philippines’ national treasure, and building a resort between the hills is an act of destruction, many said.

The controversy also caught the attention of public officials, resulting in a Senate probe into the resort – called Captain’s Peak Garden and Resort – and other similar structures within the vicinity of Chocolate Hills. It was found that the resort had been operating for several years despite not having certification specifying measures that the project must take to mitigate environmental impacts. It has since been ordered closed.

Since then, many have asked why the resort was allowed to be built in the first place and if there are loopholes in the approval process for such construction projects. Across the Philippines, there are also 248 protected areas similar to Chocolate Hills, and the recent example of careless and illegal building on natural and geological monument sites might not be an isolated one.

Mt. Apo, a protected area under the category of a natural park in Davao in the Mindanao island group, has also been found with illegal structures in its multiple-use zones. Image: Peak Visor

Apart from an investigation into Chocolate Hills, a Senate resolution has been called to look into other protected areas spoilt by commercial activities, citing the Upper Marikina River Basin Protected Landscape in Rizal province, Siargao Island Protected Landscape and Seascape in Surigao del Norte province, and Mt. Apo Natural Park in the provinces of North Cotabato and Davao del Sur, and Davao City.

Andres Muego, an expert on land use management in the Philippines, said that within protected territories set aside for their unique physical and biological significance and to prevent human exploitation, there are still “multiple-use zones” where businesses or settlements are allowed to operate, subject to limits prescribed in individual management plans.

This is usually where loopholes emerge, said the vice-chancellor of the College of Fellows of the Philippine Institute of Environmental Planners.

Either due to population increase or attempts to expand urban and agricultural sites in consideration of the need to cater to socio-economic demands, there has been an increase in establishments and settlements in protected areas across the Philippines that are approved, Muego observed.

Such establishments are mostly tourism facilities likes hotels, coffeeshops and eateries, as well as training centers and schools, some without the necessary clearances. There are also illegal activities such as quarrying, farming and tree-cutting.

At the same time, existing policies and governance structures are inadequate or not in place to curb this trend, he added.

Misaligned concerns

As the chairperson of the development council environmental committee of the Visayan region, where Bohol is located in, Muego noted that government officials at the local and national level are not aligned on their goals when deciding on what projects to approve when it comes to construction in protected areas.

There is a “disconnect”, he said, as local officials are often more concerned about bringing about positive impact to the livelihoods of their constituents, while officials from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) are evaluating projects based on their impact on the environment.

In most instances, before construction is permitted, a multi-sectoral policy-making body appointed to decide on matters related to planning and resource protection in the jurisdiction known as the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) is involved. Project owners first meet with PAMB members, but Muego said that these barangay or village captains and community leaders in attendance are often not knowledgeable about environmental impacts.

An environmental impact assessment (EIA) will usually be is conducted to identify the environmental, social and economic impacts of a project prior to construction. This is needed to procure the environmental compliance certificate (ECC), a document issued by DENR that allows a proposed project to proceed to the next stage of project planning, where approvals from other government agencies and LGUs are obtained, after which the project can be implemented. Source: Philippine Insitute of Environmental Planners, Image: HAF/ Eco-Business

In the case of the Chocolate Hills controversy, the barangay captain issued the clearance for building the resort, Muego pointed out. What should be in place is a technical committee “which knows how to assess the preliminary environmental impacts of a project”, suggested the veteran environmental specialist. “Otherwise, the projects that do not conform to the protected area’s conditions and design guidelines will still get clearance.”

For now, the PAMB, though a recommendatory body, wields significant power. Muego said DENR officials might be issuing the environmental compliance certificate (ECC), a crucial document needed for a proposed project to proceed, but it is the PAMB’s clearance that they defer to.

“With the increased number of local, congressional, and regional officials in the PAMB membership, there is a risk of having political powers more control and authority, affecting the DENR’s oversight functions over the board,” he said.

Other suggestions that Muego has includes enforcing a standardised protocol where there is stricted adherence to the district’s protected area management plan (PAMP) which delineates which areas are where no establishments are allowed and which are the multiple-use zones.

Muego said he has observed that the PAMP is no longer referred to during meetings with project owners. He also suggests getting project owners to submit an “initial environmental examination” that describes the environmental conditions of a project in the early stages of the approval process. This would “educate PAMB members of the project risks” before they make any decisions, he said.

Scrutiny returns to Cebu’s protected watershed area

Another example of a protected area which has a multiple-use zone is the Central Cebu Protected Landscape (CCPL), which is a watershed and haven for endangered birds and trees species in central Cebu, a province located in Central Visayas region.

Cebu, the second most populous province in the country, has a population of 3,325,385 as of 2020. It has been steadily growing at an annual average of 2.63 per cent five years before.

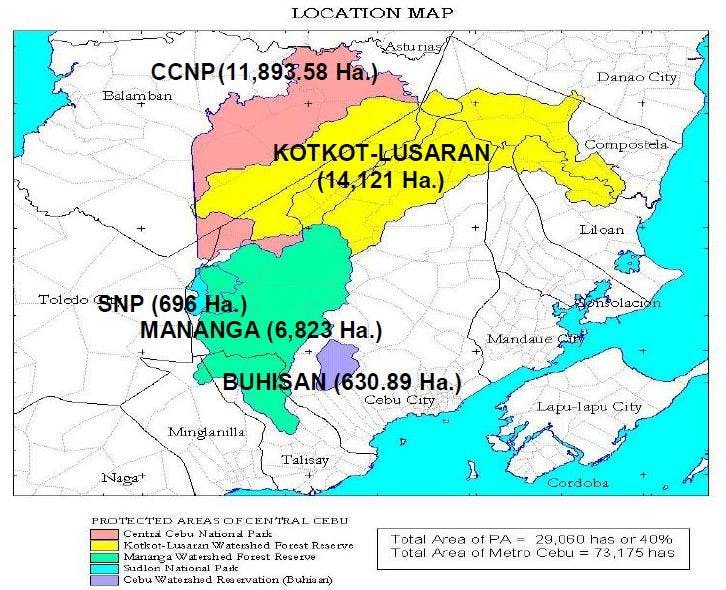

The CCPL spans 29,060 hectares that cover parts of the central Cebu cities and the municipalities. Due to the increase in the populations of surrounding barangays and its spillover effects, the number of residential and commercial establishments in the zone has creeped up.

The Central Cebu Protected Landscape covers parts of the central cities like Cebu City, Toledo, Talisay, and Danao and the municipalities of Balamban, Minglanilla, Consolacion, Liloan and Compostela. Image: Ramon Cavada Sevilla

In 2011, the government stopped land titling in forest lands, including the CCPL, to limit further overunning of the population into protected sites.

The processing of applications for lease, license or permit of any project within the identified area, as well as the acceptance of new applications were prohibited, except for those that are compatible with the objectives of the protected area such as conservation activities.

However, existing landowners whose properties were titled at least five years before the order could still sell, exchange, donate or subdivide their property,

But Muego noted cases in CCPL where some municipalities have unoffically issued tax declarations, which buyers not qualified to be tenured occupants present as their ‘“rights” to the property.

“This could have been done by certain officials or employees in the local government unit under the table. For establishments which are unable to obtain such tax declarations, they strike an informal arrangement with the original occupants landowners by paying them a certain amount to vacate the property,” he said.

The Central Cebu Protected Landscape (CCPL) is the main source of water supply of Cebu City. It is also home to Indigenous birds such as the Cebu flowerpecker, streak-breasted bulbul, and black sharma, as well as rare trees like the Cebu cinnamon tree. Image: Adrenaline Romance

As a result, the district has been teeming with private owners who sell their lots to property developers to create tourist attractions like gardens, along with coffeeshops and restaurants.

He said: “It is not just Chocolate Hills or Cebu which face these issues, but most protected areas in the entire country do, especially those covering large tracts of land, which are harder to monitor. If these are not checked then we will have more cases of illegal structures, and continue to put our natural wonders at risk.”

Want more Philippines ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Philippines newsletter here.