When a group of clean energy developers from Singapore-based solar provider Sunseap arrived in Ninh Thuan province in the south of Vietnam two years ago, they found arid land and extreme weather conditions causing farmers to struggle to make ends meet.

The province is among the least developed regions in the country, said Lawrence Wu, president and executive director at Sunseap, but it happens to have two things in abundance that make it favourable for solar deployment—space and sunshine.

Two years later, My Son Commune, a group of villages in the province, has changed. A 168 megawatt (MW) solar farm, built by Sunseap in partnership with InfraCo Asia, a Singapore-headquartered catalyst for infrastructure development, has created permanent jobs for more than 200 villagers and generates enough electricity to power 200,000 households.

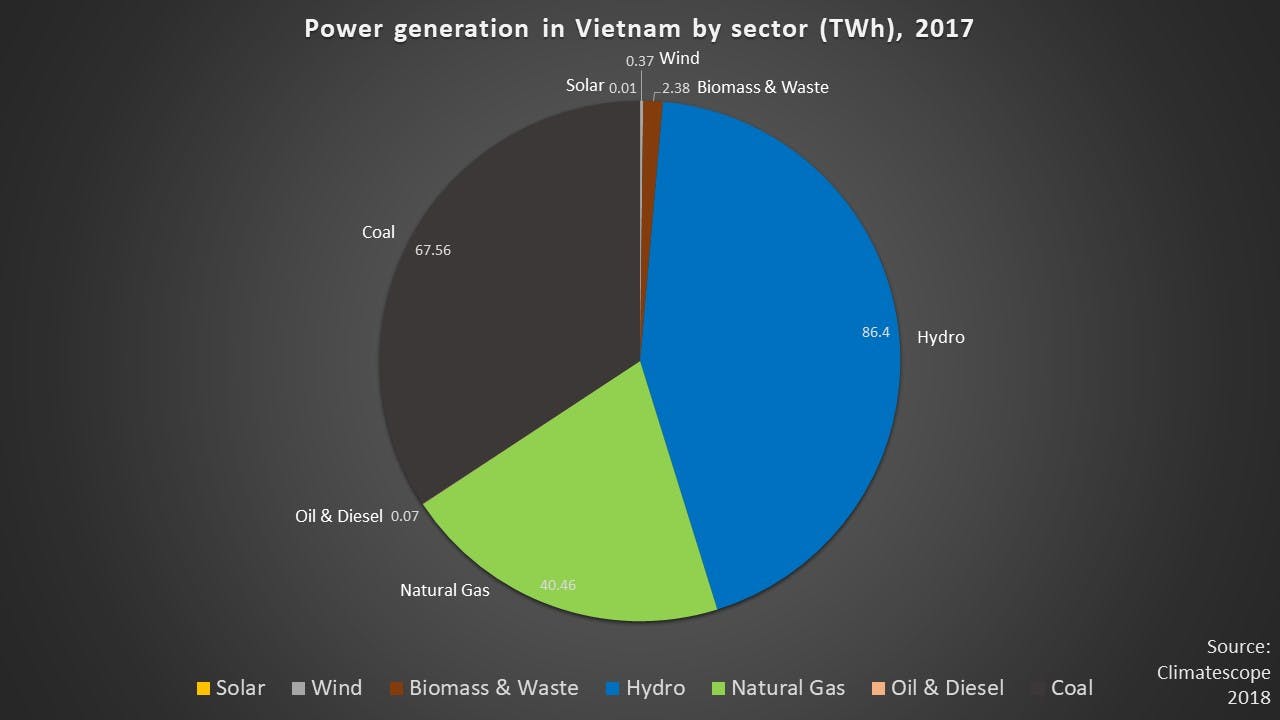

Vietnam’s energy mix has historically been dominated by hydropower, coal and gas, but realising the downside of overreliance on these resources, the nation decided to exploit its untapped potential in solar and wind power to bring more sustainable energy to its people.

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Vietnam by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

The government’s move to raise the feed-in tariff paid for wind power exported to the grid, and to introduce tariffs for solar have made projects like Sunseap’s commercially viable and catapulted Vietnam into a leadership position for clean energy deployment in Southeast Asia, Nadhilah Shani, research analyst on policy of the research and analytics programme at Jakarta-headquartered intergovernmental organisation Asean Centre for Energy told Eco-Business.

From Vietnam’s ramped up clean energy incentives to the Philippines’ recently introduced renewables portfolio standard, which requires distribution utilities to source more power from renewables, to Indonesia’s announcement that it would start to transition away from coal, change is afoot in Southeast Asia, a region that has been the slowest in the world to adopt clean energy.

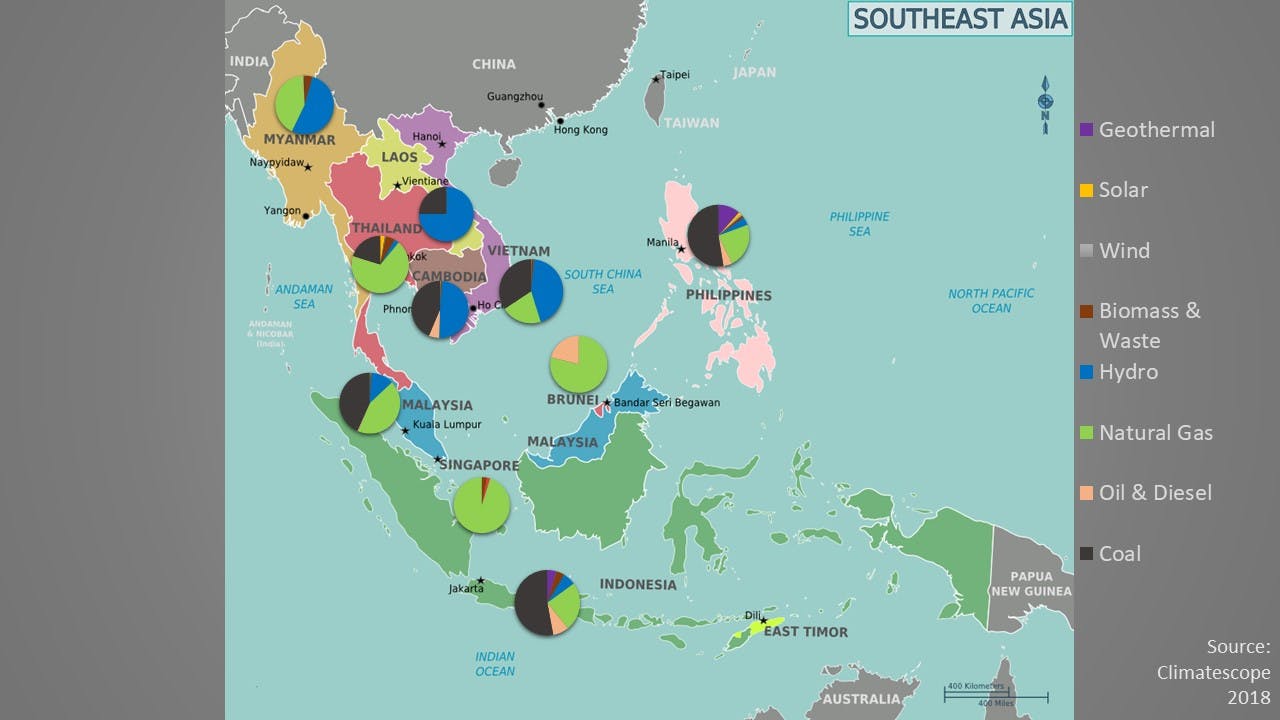

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Southeast Asia by sector, 2017. Image: Wikipedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

Progress, however, varies greatly across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), and despite tremendously diverse economies and resource distribution among member states, what the differences appear to boil down to is government policy.

A political choice

Countries show varying support for renewables, and in most of them, clean energy still faces persistent policy and financial challenges.

Assaad Razzouk, chief executive officer at Sindicatum Renewable Energy, a global clean energy company headquartered in Singapore, told Eco-Business: “Southeast Asia is the worst-performing region in the world regarding the deployment of renewables but within it, there are different stories. And when you contrast the different countries, you can clearly see the difference that policy achieves.”

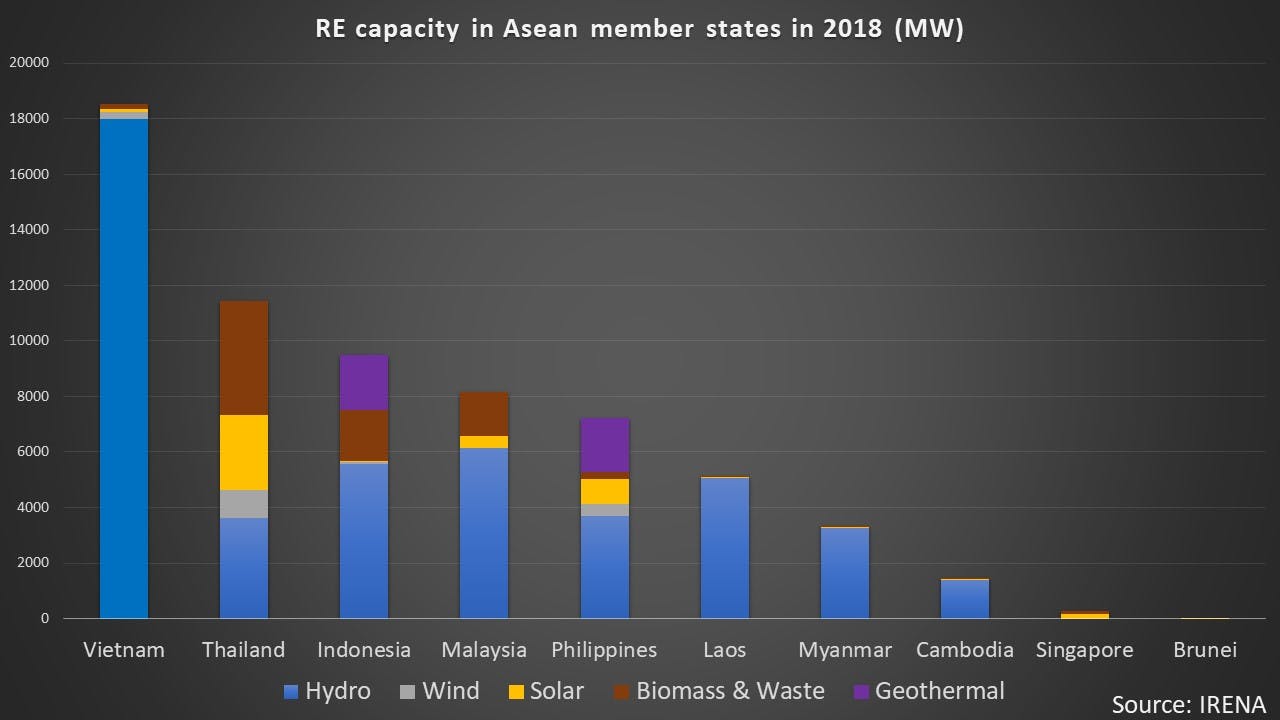

Eco-Business graphic: Renewable energy capacity by source in the Asean member states in 2018 (MW). Source: IRENA

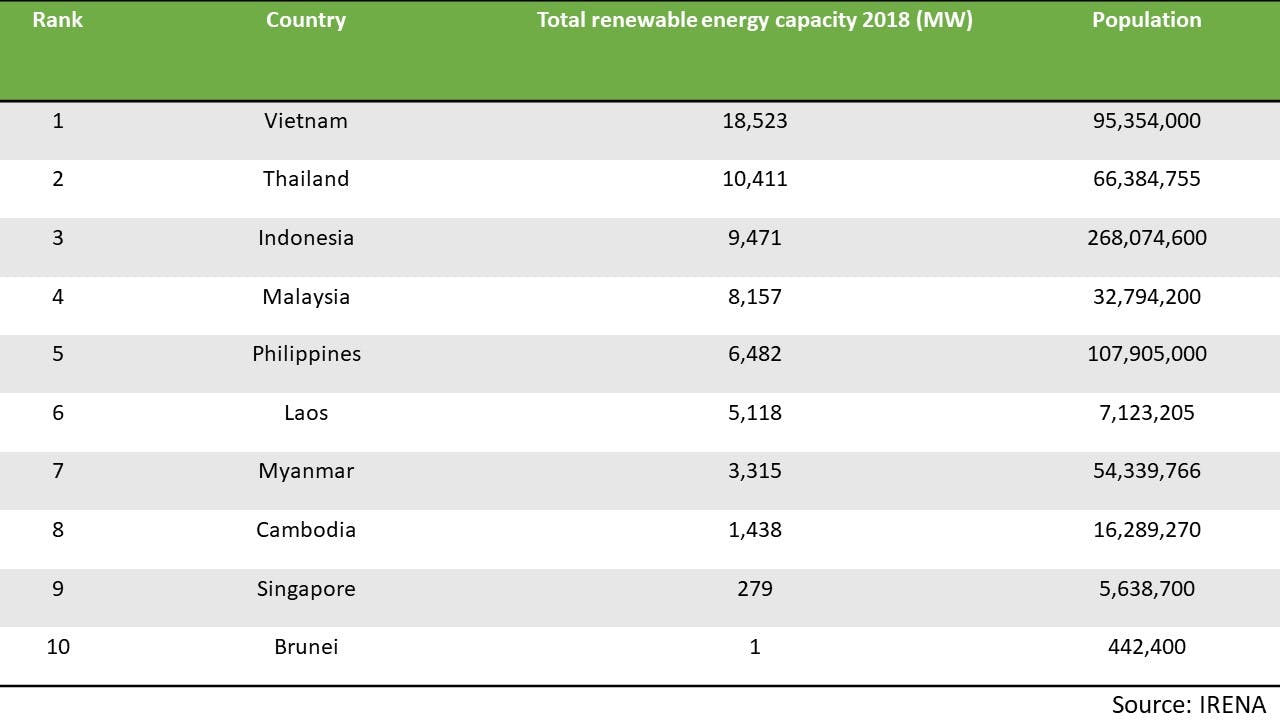

Eco-Business graphic: Total renewable energy capacity—Asean country ranking 2018. Source: IRENA

Indonesia’s location above several converging tectonic plates has enabled the country to become the region’s top-user of geothermal energy just as the multitude of rivers traversing Vietnam have made it possible for the nation to generate more hydropower than any other Asean member state. But exploiting specific resources to generate electricity is ultimately a political choice.

Shani of Asean Centre for Energy said: “Certain Asean countries are ahead because they have been implementing and revising their renewable energy policies for some time to push the deployment of renewables in their country.”

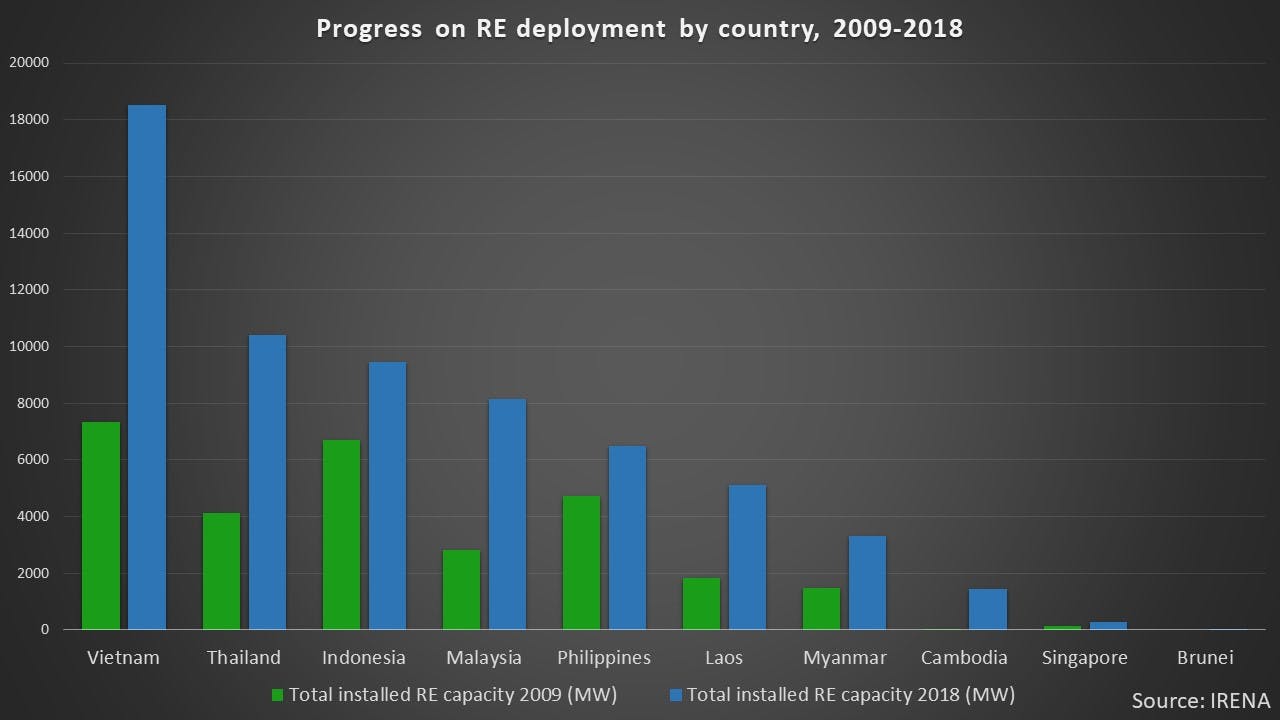

Eco-Business graphic: Progress on RE deployment by country, 2009-2018. Source: IRENA

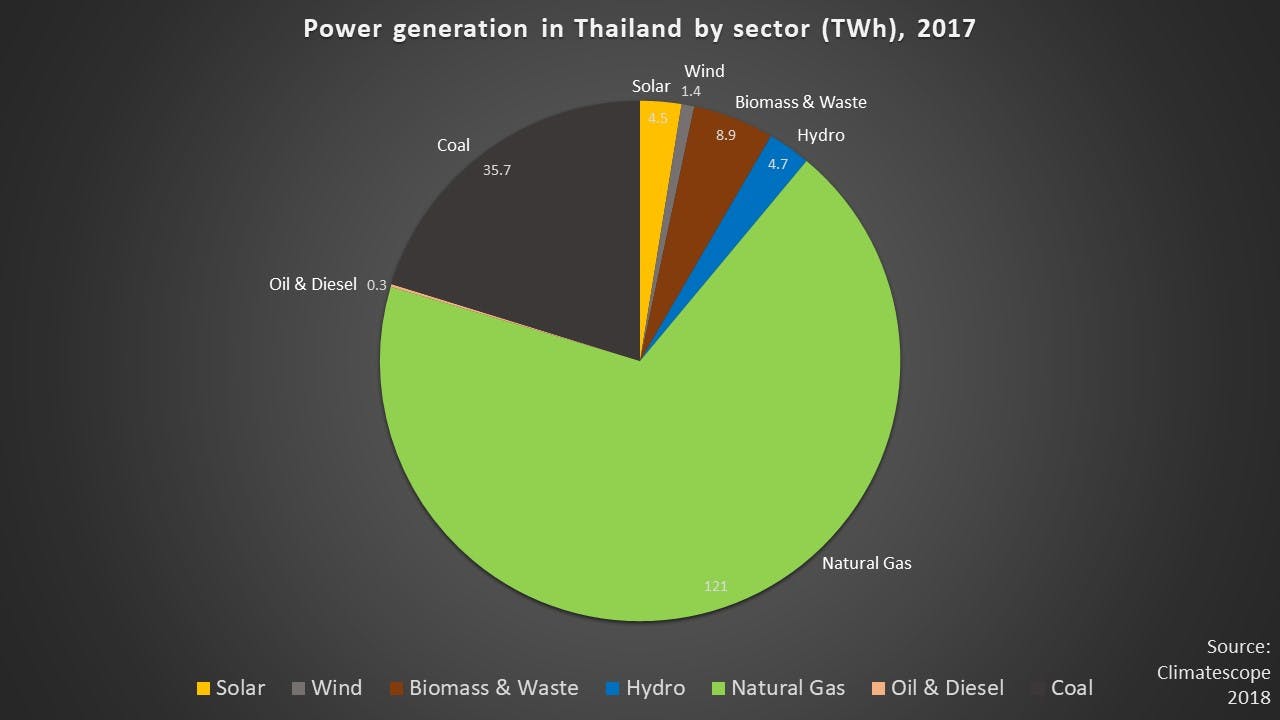

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Thailand by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

Thailand, for instance, has been incentivising investment in solar projects for more than a decade and now reaps the benefits of this consistent support, being Asean’s front-runner in installed solar, wind and biomass capacity, Shani said. By contrast, the tiny oil and gas kingdom of Brunei Darussalam, which is just as sun-drenched, has installed a mere 1 MW of solar power.

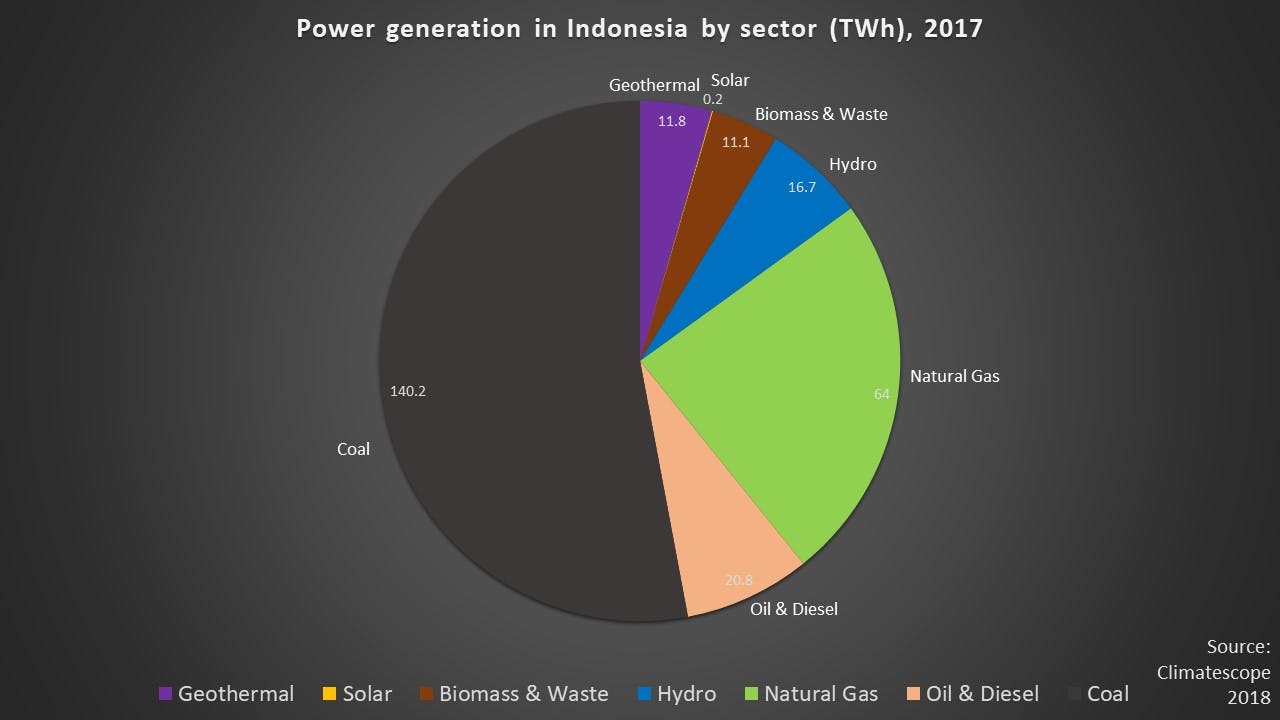

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Indonesia by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

For the world to head off the worst effects of climate change, switching power generation from coal to renewables is almost nowhere as important as in Indonesia. The archipelago—Southeast Asia’s biggest consumer of energy—is expected to become the world’s fourth most powerful economy by 2050, and while ranking third for total renewable energy capacity in the region, it still remains Asean’s top-user of coal.

The problem is that the country’s state-owned utility company Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) may not be fully incentivised to commit itself to renewables, says management consulting firm AT Kearney in its new report titled Indonesia’s Energy Transition: A Case for Action. PLN, after all, owns most of Indonesia’s coal power plants.

The coal industry has also engendered lucrative business relations, Razzouk said, noting that this year alone, PLN will pay out $10 billion in cash for coal to fuel its power plants. And the ensuing vested interests and anti-renewables incentives have undermined all efforts at reform that could potentially challenge coal’s leadership position, he added.

A regional clean energy policy expert, who wished to remain anonymous, added: “Crony capitalism and entrenched vested interests in the incumbent supply chain are strong barriers to Southeast Asia’s renewable energy transition.”

“The clean energy transition is a clear dilemma for Indonesia,” said Nicolas Payen, chief executive officer at Singapore-headquartered clean energy investment firm Positive Energy Limited. “As producing solar and wind energy becomes cheaper than running a coal power plant, Indonesia may quickly be sitting on a dying horse.”

The coming years will show whether the administration will follow through on President Joko Widodo’s statement of intent to phase out coal.

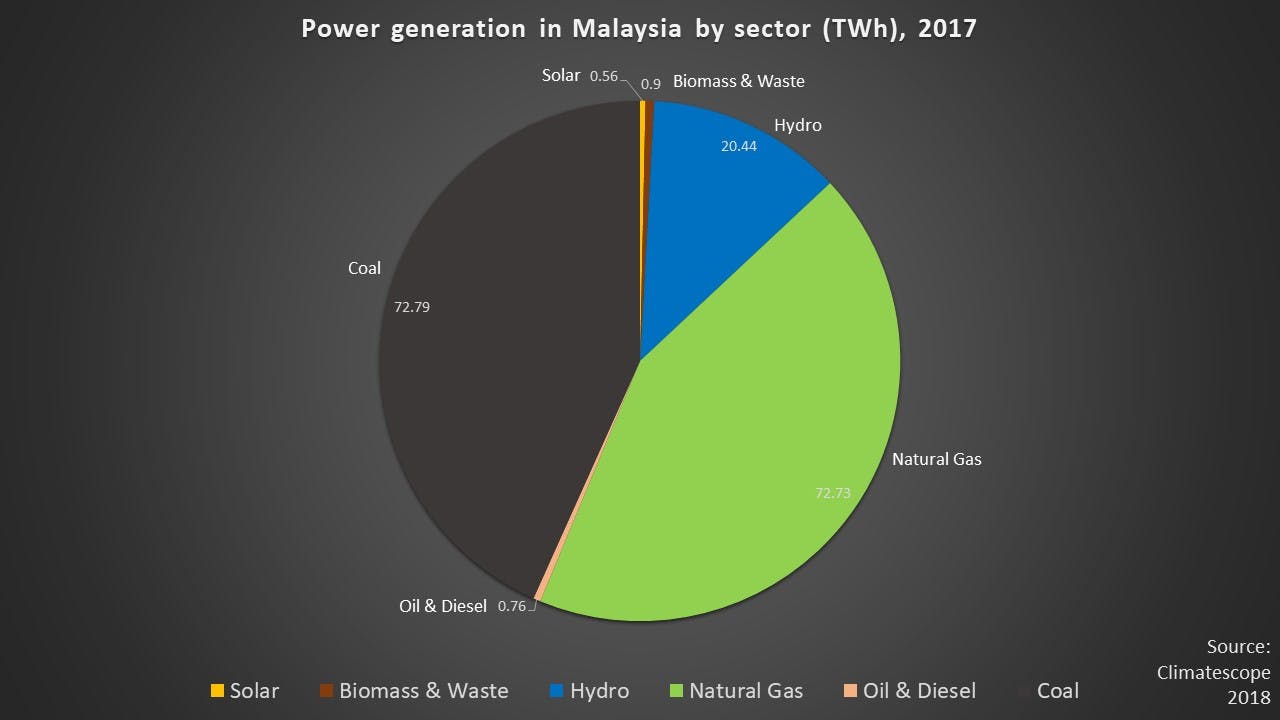

In Malaysia, meanwhile, things are now moving fast, according to Sinha of European Climate Foundation. The government, she said, is introducing a net energy metering programme to catalyse renewable energy growth in the country, which ranks fourth among the Asean member states for total renewables capacity.

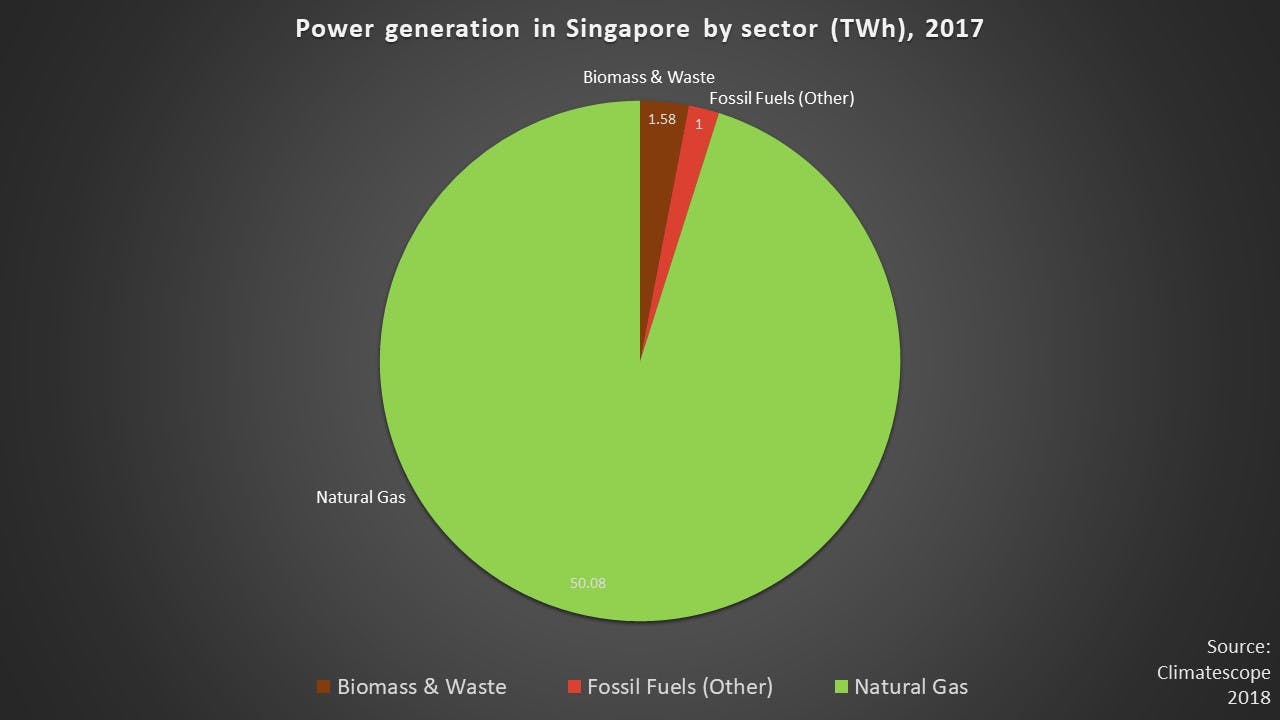

Malaysia’s neighbour Singapore has made such little progress over the past decade that a magnifying glass is needed to see the difference. But while the prosperous city-state has traditionally been reluctant to take action, it now seems willing to allow renewable energy to flourish. In the Straits of Johor, Singapore is building one of the world’s largest offshore floating solar systems that is expected to start operating later this year.

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Malaysia by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

Hydropower taking the lead

Hydropower, among the cheapest of renewable energy sources, leads clean power production in Southeast Asia, accounting for more than half of generated electricity in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos.

But while emissions-free, hydropower has been often associated with social conflict and widespread environmental impacts as the construction of hydroelectric dams has displaced communities and wiped out aquatic ecosystems. A July report by Global Witness found that of the 164 environment and land defenders killed in 2018, 17 were killed protesting against dam projects.

Adding to such problems are growing safety concerns. Last year’s dam collapse in Laos, for instance, displaced thousands, drawing international criticism of the government’s relentless pursuit of hydropower and its poor construction standards. However, the incident doesn’t seem to have made the country give up its dream of becoming the ‘battery of Asia’.

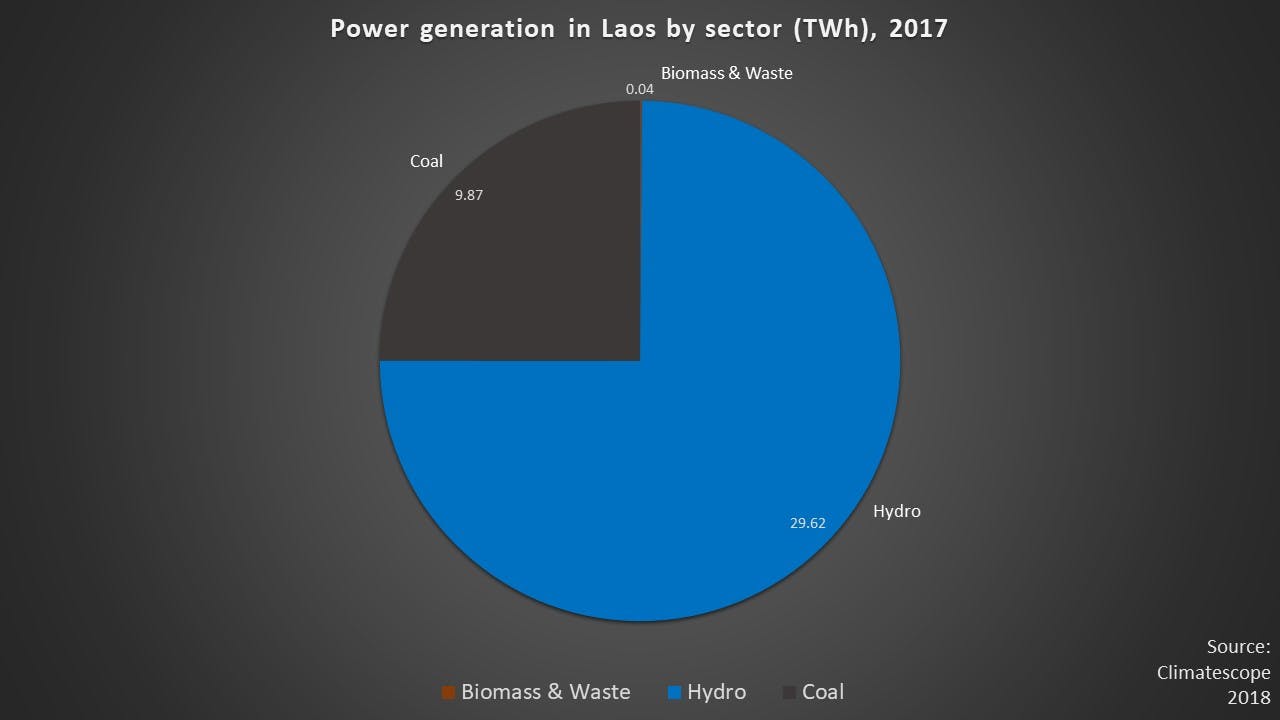

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Laos by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

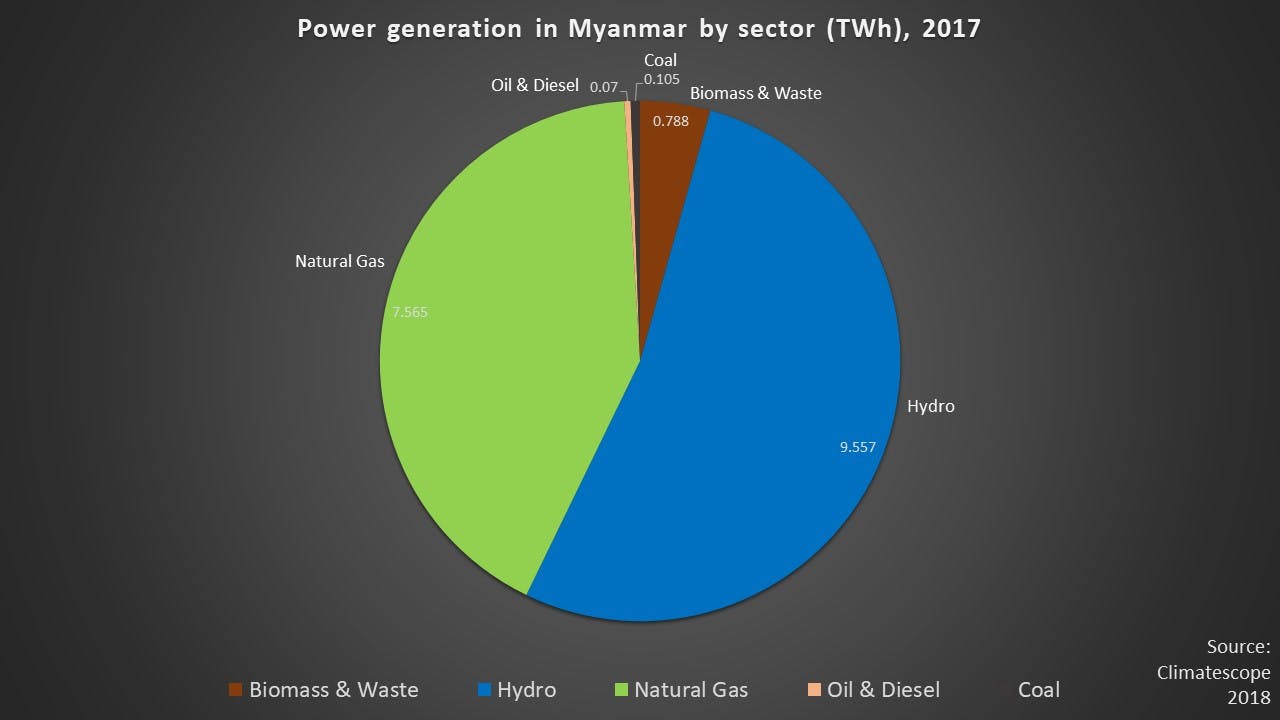

Myanmar, on the other hand, is a special case. Hydropower constitutes 65 per cent of its power mix, but the country also ranks at the bottom for energy access in Asean, with more than 40 per cent of its people still living in the dark.

Whether Myanmar will allow coal and gas to take over the reins—a move that would set the country back dramatically on its emissions targets—or deploy off-grid solutions to meet its lofty goal of providing full energy access by 2030 remains to be seen. Razzouk commented that rooftop solar and renewable energy microgrids are the “obvious solution” in Myanmar.

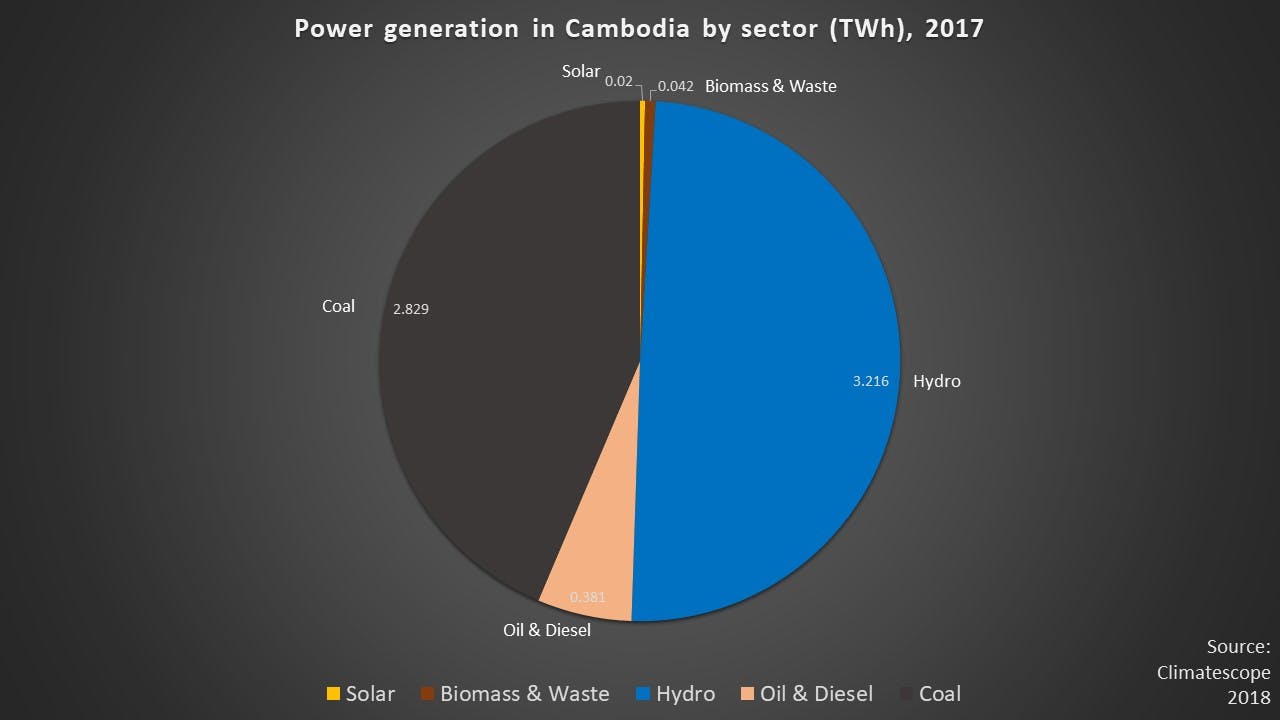

A solar auction policy implemented in Cambodia has made the renewable energy sector increasingly attractive in the country, Sinha of European Climate Foundation said. But hydro dominates Cambodia’s energy mix, and the country relies heavily on electricity imports to power its growing economy.

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Myanmar by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

Develop first, clean up later

The reasons why Southeast Asia has resisted the global trend away from fossil fuels are diverse and convoluted. Among them, said Shani of Asean Centre for Energy, is that bringing affordable power to millions of people still lacking access to it, and the hasty pursuit of economic progress have taken precedence over environmental concerns.

As such, Asean countries have prioritised the cheapest and most abundant sources of energy available. Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar—all traversed by some of Southeast Asia’s greatest waterways—source most of their power from hydro; Brunei Darussalam from natural gas and oil; and Indonesia and the Philippines from coal.

The link between renewables and climate change is crystal clear.

Assaad Razzouk, chief executive officer, Sindicatum Renewable Energy

Such priorities are reflected in energy policies, said Shani. And the resulting adverse policies in turn block renewable energy deployment, reads the report by AT Kearney.

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Cambodia by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

High costs remain a key obstacle to renewables development. Peter Godfrey, managing director at Singapore-based Energy Institute Asia Pacific, said coal was at present still more cost-efficient compared to most clean energy technologies.

But costs for solar and wind power technologies will continue to plummet as technology improves and developers gain experience, while the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, increasing resource scarcity and ageing thermal power stations are set to push up the costs of fossil fuel-powered electricity generation.

It is estimated that by 2020 onshore wind and solar photovoltaics will be consistently less expensive sources of new electricity than the cheapest coal, oil or natural gas options, without financial assistance. Already, biomass and hydropower, both at a mature stage of development, often beat fossil fuels on cost, and solar photovoltaics have reached grid parity in the Philippines and Singapore, and fallen into the fossil-fuel cost range in Thailand.

Payen of Positive Energy Limited, said: “Wind and solar are becoming extremely competitive with conventional technologies. From an economic point of view, there will soon no longer be a valid reason not to opt for clean energy. Therefore, boosting renewables represents a real opportunity for the Asean region.”

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Singapore by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

But another barrier standing in the way of greater renewables deployment is energy security, particularly given Southeast Asia’s notoriously unreliable energy distribution networks.

Even where solar and wind can compete on affordability, Gilles Pascual, partner of Asean Infrastructure Advisory at Ernst & Young in Singapore, said utilities often still grapple with intermittency and variable output that expose underdeveloped grids to stability issues. Surges of solar energy, after all, fade quickly by dusk.

And as Vietnam races ahead, its grid development struggles to keep up. This means electricity companies may not be fully convinced to go green just because renewables are getting cheaper, as they still need to take into account the investment needed to go into the grid, said Pascual.

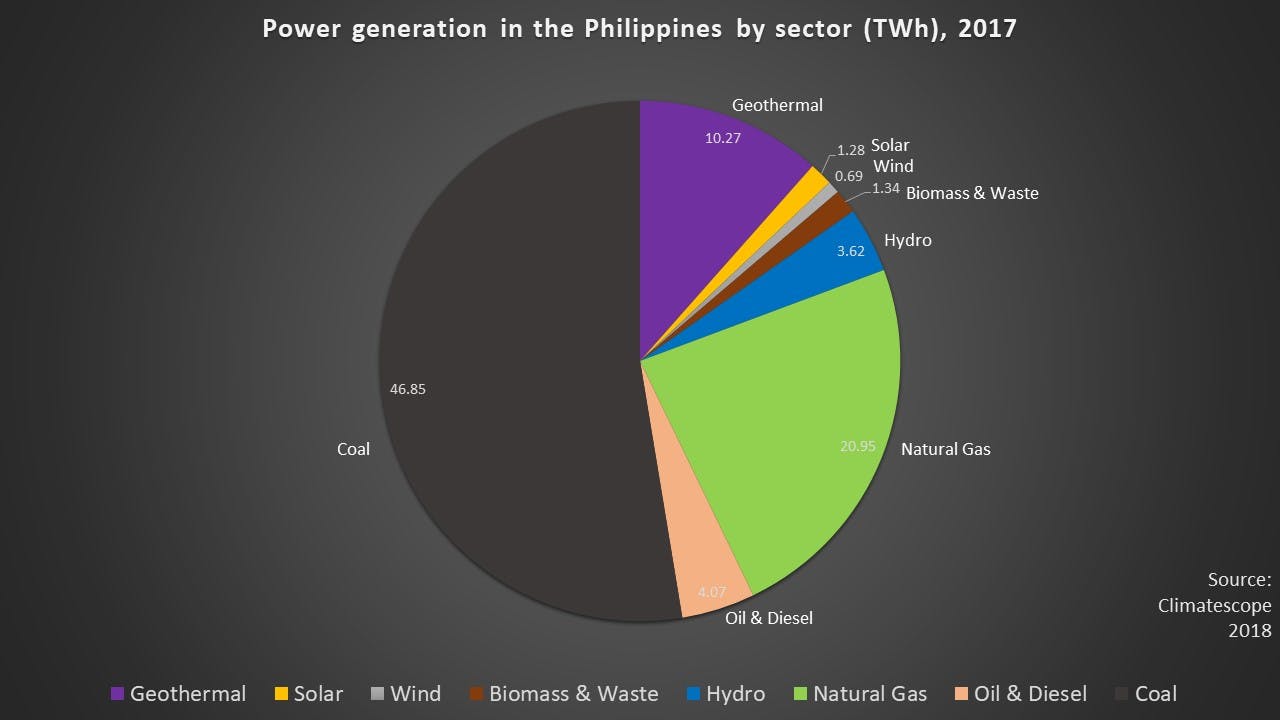

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in the Philippines by sector (TWh), 2017. Source: Climatescope, BloombergNEF

Policy revamp needed

Meeting Asean’s aspirational target of generating 23 per cent of its power from renewable sources by 2025 will not only require a $27 billion investment annually, said a spokesperson at Abu Dhabi-headquartered intergovernmental organisation International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), but also more favourable policies. At the moment, clean energy only accounts for 12.5 per cent of generated electricity in Southeast Asia.

Most importantly, policies must be consistent and send a clear signal to boost investors’ confidence, the spokesperson said. For instance, governments could facilitate access to affordable financing and level the playing field for renewables through fiscal incentives, carbon pricing schemes and the removal of fossil fuel subsidies.

Fossil fuel subsidies—one of the key barriers to moving renewables forward—are paid in all Asean countries except for the Philippines, Singapore and Cambodia, said Shani of Asean Centre for Energy.

Summary of renewable energy incentives and policies in Asean. Red indicator: no longer valid; (*): pilot project. Source: Asean Centre for Energy

The success of policy instruments to support renewables also depends on their design, requiring careful tailoring to the local context, a recent IRENA report pointed out. Vietnam, for example, differentiated its tariffs for solar by regions, offering higher support in the cloudy north to deploy renewables more evenly across the country in order to facilitate infrastructure development and prevent grid instability.

Hòa Bình Dam in Vietnam. Hydropower accounts for the largest share of clean energy in Southeast Asia, but the construction of hydroelectric dams has entailed environmental damage and social conflict. Image: Zniper, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr

Even in Vietnam, however, there is work to do, said Pascual of Ernst & Young: “Vietnam has a strong policy with ambitious targets, but the regulation is not conducive to international financing because the off-taker, Vietnam Electricity (EVN), is less creditworthy due to the lack of government guarantee on EVN’s payment.”

A race against time

Revamping systems of energy production—the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions globally—is one of the key actions countries can take to meet their commitments made under the Paris Agreement and combat climate change.

But Southeast Asia is not deploying cleaner technologies nearly fast enough to slow the growth of emissions as it experiences an increasingly ravenous hunger for energy. Power demand in the Asean region shot up by 80 per cent between 2000 and 2017 in the wake of rapid industrialisation, population growth and expanded access to energy, a report produced for this year’s Ecosperity conference in Singapore has found.

This sharp upward trend, the report reads, is projected to continue throughout the coming decades. Southeast Asia—a region among those at greatest risk from climate change—stands at a crossroads in terms of its energy future, with a perpetuation of current policies and investment priorities set to put it on track for a power mix dominated by fossil fuels until 2040.

And the earth will not take kindly to continued inaction and political inertia —nor will Asean’s citizens, said Razzouk of Sindicatum Renewable Energy.

“The link between renewables and climate change is crystal clear. We need to have the world powered 60 per cent by renewables by 2030 as well as a large-scale reforestation strategy in order to have a chance of averting climate catastrophe,” he said. “The countries in this part of the world have to pull their weight because their citizens will be increasingly aware how vulnerable they are to climate change.”