Official data shows that at least 1.9m hectares (19,000km2) or 8 per cent of wheat land in China have been affected by a sustained spate of rains – with “agricultural challenges” set to continue throughout the rest of the year.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and World Bank both stress that further loss and damage is expected across China’s farming sector as global temperatures continue to rise.

But what, specifically, is happening to China’s arable land? And how does China plan to minimise the negative impacts of climate change on its wider food system?

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at China’s cropland policies.

What challenges does Chinese farming face under climate change?

In 2022, China suffered from its worst heatwave and drought in six decades. The ministry of agriculture and rural affairs stated at a press conference last August that the agricultural sector was facing “growing risks” as a result of extreme weather and shifting planting conditions brought about by climate change.

This summer, severe drought continued to affect China in June and July, while a torrent of floods brought on by typhoons followed in August. The heavy rains have destroyed corn and rice crops in north China, while in central China’s Henan province more than 20m tonnes of wheat were lost in June alone.

“

Food security is a tangible and rigid attribute, whereas forestry is a soft and elastic one…After satisfying all basic land uses (residential, transportation, etc), forestry should be promoted as a way to improve ecosystem quality and sustainability.

Haishun Yang, associate professor, University of Nebraska – Lincoln

Although the agriculture ministry insists the country has experienced a “summer harvest”, the summer’s grain output decreased 2.55bn jin (1.53m tonnes) from last year’s total of 147m tonnes.

However, the US department of agriculture predicts that 2023 may not end up being a poor harvest year for China. Only sunflower seeds, barley and cotton are likely to see a reduction in production. The output of main crops, including corn, rice and wheat, would surpass the average output of the past five years.

Corey Lesk, research associate from the geography department at Dartmouth College in the US, tells Carbon Brief that “in some sense, China’s crops are not that vulnerable to climate warming”.

Broadly, China’s main food crops are wheat in the north and rice in the south. “The south is already warm and sub-tropical,” says Lesk, “[and rice] is well-understood to be more resilient to extreme heat”.

In the north, Lesk says warming will lengthen the growing season and increase yield potential for wheat as well as enable farmers to “plant multiple crops” in a single year at a higher latitude. “Combining these effects, in the north, crop models show only small yield losses under plausible warming scenarios,” he adds.

Haishun Yang, an associate professor from the department of agronomy and horticulture at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln, shares a similar view:

“Globally speaking, crop yield per ground area as well as the total crop production have been increasing constantly along with the climate change. China is the same as most parts of the world.”

However, Lesk warns that “there are caveats”. He says: “Those crop models are known to not realistically simulate the impact of heat extremes, in particular, so likely underestimate true impacts [of climate change].”

The most recent IPCC report has “high confidence” that, globally, “climate-related extremes have affected the productivity of all agricultural and fishery sectors, with negative consequences for food security and livelihoods”. China is no exception.

Dr Zhang Hongzhou, research fellow from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, tells Carbon Brief:

“More occurrences of extreme climate events, such as flood, drought and typhoon, will certainly present major risks to the country’s [China] food security both in the short term and long term.”

“While certain regions or crops might benefit from a warm climate, based on existing studies, the overall impact seems to be negative. In short, climate change is a major threat to the country’s [China’s] food security.”

What impact will climate change have on China’s food security?

A study published earlier this year in Nature found that extreme rainfall has suppressed Chinese rice yields by around 8 per cent over the past two decades. A review of hundreds of studies, published in the journal International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, concluded that rice yields in China were likely to decline by 5-25 per cent after the 2060s.

China’s third national assessment report written by the ministry of ecology and environment in 2018 already acknowledged the negative consequences. It said:

“Climate change has significantly impacted cropping systems in China, as well as the occurrence, development and damage caused by disease and pests, and the growth, development and yield of crops.”

The report also said that climate change would bring less reliable rains, the spread of dangerous pests and shorter growing seasons for many crops.

Meanwhile, Lesk tells Carbon Brief that climate change directly threatens the farming of pork – China’s most consumed meat by volume.

China consumes about 45 per cent of the world’s pork at more than double the world’s average per capita consumption. (See more on Carbon Brief’s analysis on China’s food system).

Lesk says pork in China is “very dependent” on soya beans, which accounts for up to 90 per cent of a pig’s feed. Soya beans, although mostly imported from the Americas, are “quite vulnerable to future extremes”.

Lesk thinks that “while the climate risk to China’s own crops is perhaps somewhat lower than other countries, its exposure to distant risks is quite high in this respect”.

Tang Renjian, China’s minister of agriculture and rural affairs, has stated that the Chinese population needs 700,000 tonnes of grain, 98,000 tonnes of edible oil, 1.92m tonnes of vegetables and 230,000 tonnes of meat on a daily basis.

This means the nation’s “cultivated land must be kept at 1.8bn mu (about 120m hectares), which is the bottom line and cannot be lowered” to meet such demand, he said.

So, does China have enough cultivated land?

How much arable land does China have?

The Chinese government claims that China had 127.6m hectares of arable land at the end of 2022, which is about 9 per cent of the world’s total.

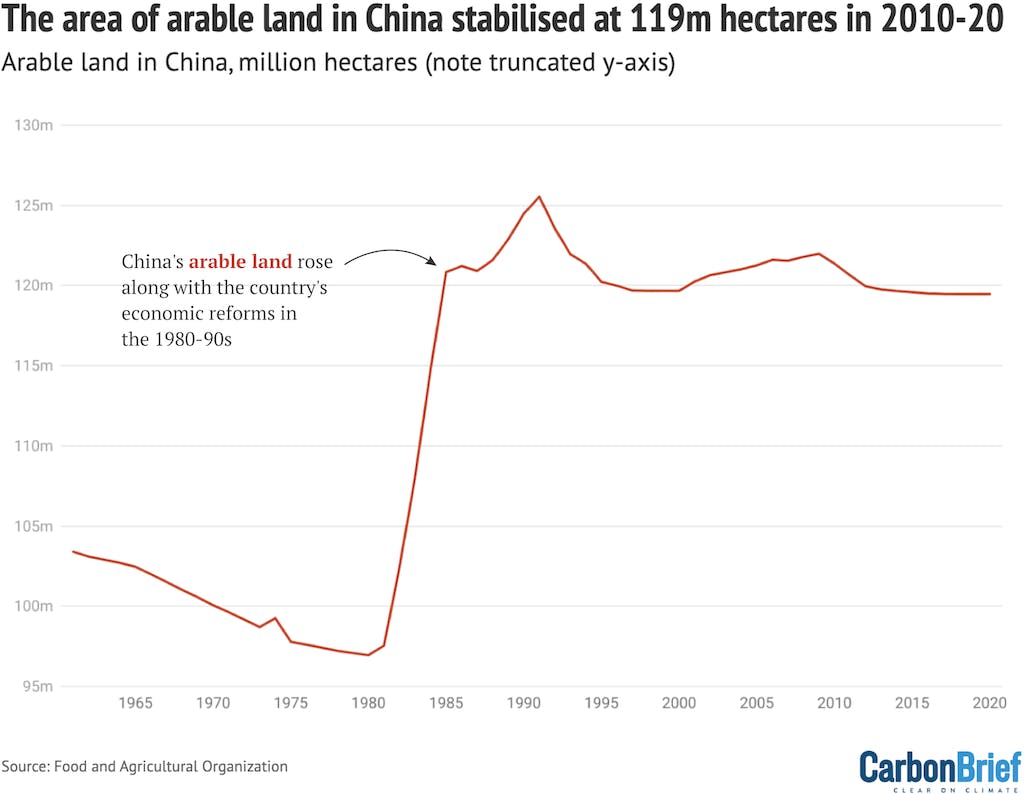

The most recent data from the Food and Agriculture Organisation shows that China’s arable land remained at around 119m hectares (12 per cent of its land area) between 2012 to 2020, which is smaller than the Chinese official data, which shows 128m hectares, as of 31 December 2019.

As the chart below shows, the area of cultivated land has slowly decreased over the past 10 years, after seeing a rapid increase in the 1980s in line with China’s economic reform in the rural areas. The Chinese ministry of agriculture and rural affairs announced a loss of 113m mu (7.5m hectares) in the summer of 2021.

Change of arable land in China in hectares from 1961-2020. Source: FAO.