While the uptake of renewable energy in Southeast Asia has remained slow and laborious, solar and wind power producers are increasingly seeking supplementary income via a parallel market for certificates that verify their generation of clean electricity.

This dynamic has propelled the region to become one of the fastest growing originators of such “renewable energy certificates”, or RECs, which corporates buy as they work towards decarbonisation goals.

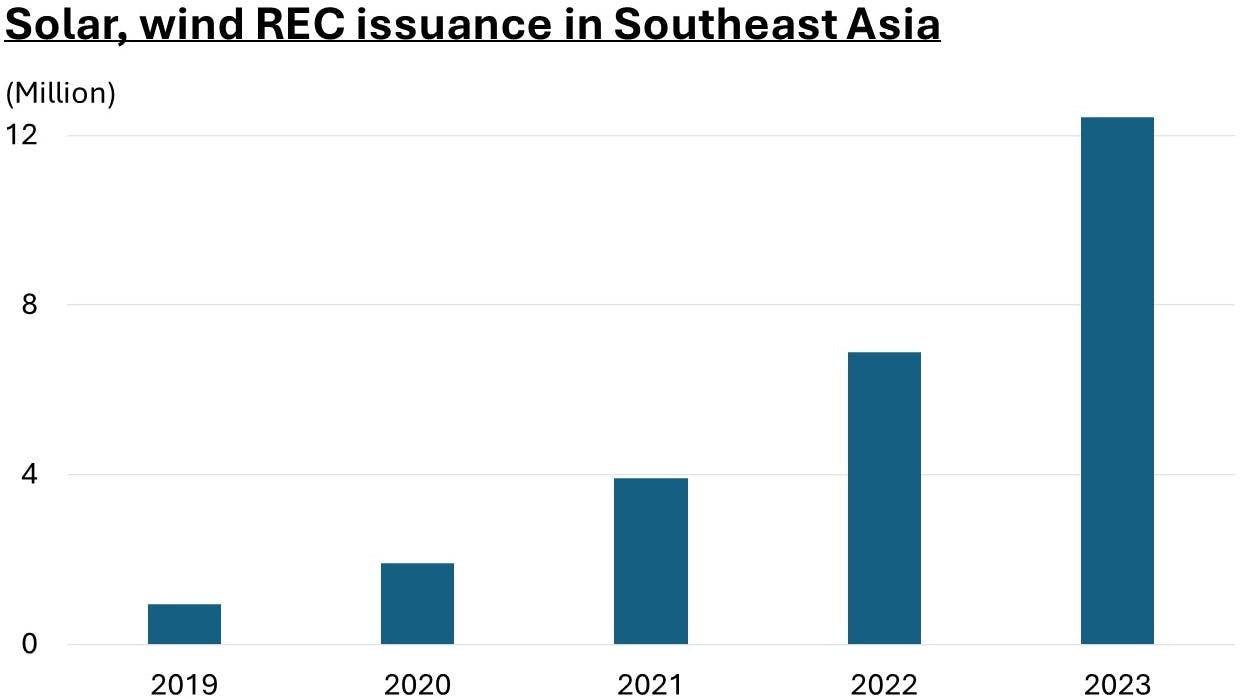

Solar and wind REC issuances from Southeast Asia rose by almost 13 times between 2019 and 2023, data from two major international registries show. Aided also by the scale-up of renewables in Vietnam, supply growth for RECs in Southeast Asia was higher than the global average, which grew by nine times over the same period.

Earnings from RECs remain generally small, but insiders say they help with cash flow amid challenging economic conditions, and as a carrot for attracting investors.

But market growth could be a double-edged sword. The RECs system has been criticised for allowing buyers – including large businesses – to overstate their green credentials. There are efforts to tighten regulations, though by its basic principles RECs enjoy some leeway compared to carbon credits in emissions accounting.

Regional players Eco-Business spoke to say RECs create a net environmental benefit in Southeast Asia, where financing options are limited, while warning against overreliance on a variable income stream.

Exponential growth

In 2023, almost 12.5 million RECs, each representing 1 megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity generated, were issued by solar and wind project owners in Southeast Asia. This is up from under 7 million in 2022 and under 1 million in 2019.

These figures were tabulated from data in two major global REC registries, I-REC and TIGR, which hosts renewable energy installations across large swaths of Asia, Australia, Africa and the Americas. Canada, western Europe and the United States largely use other standards.

Eco-Business graph. Data: I-REC, TIGR registries.

On platforms like I-REC and TIGR, RECs are sold separately from electricity, often to businesses who aren’t directly buying power, or on the same power grid. For renewables generators, the draw is the extra income. REC buyers, on their sustainability reports, can subtract an equivalent portion of their fossil-based electricity consumption – and the corresponding emissions – even if they did not use the green electricity associated with the certificates bought.

RECs have been around for decades, and have become increasingly popular among large corporates such as Google, Samsung and Starbucks. Their use case is somewhat similar to carbon credits, although in accounting lingo, RECs “reduce” a company’s emissions specifically from electricity use, while carbon credits “offset” the remaining emissions a company produces after other sustainability efforts have been factored in.

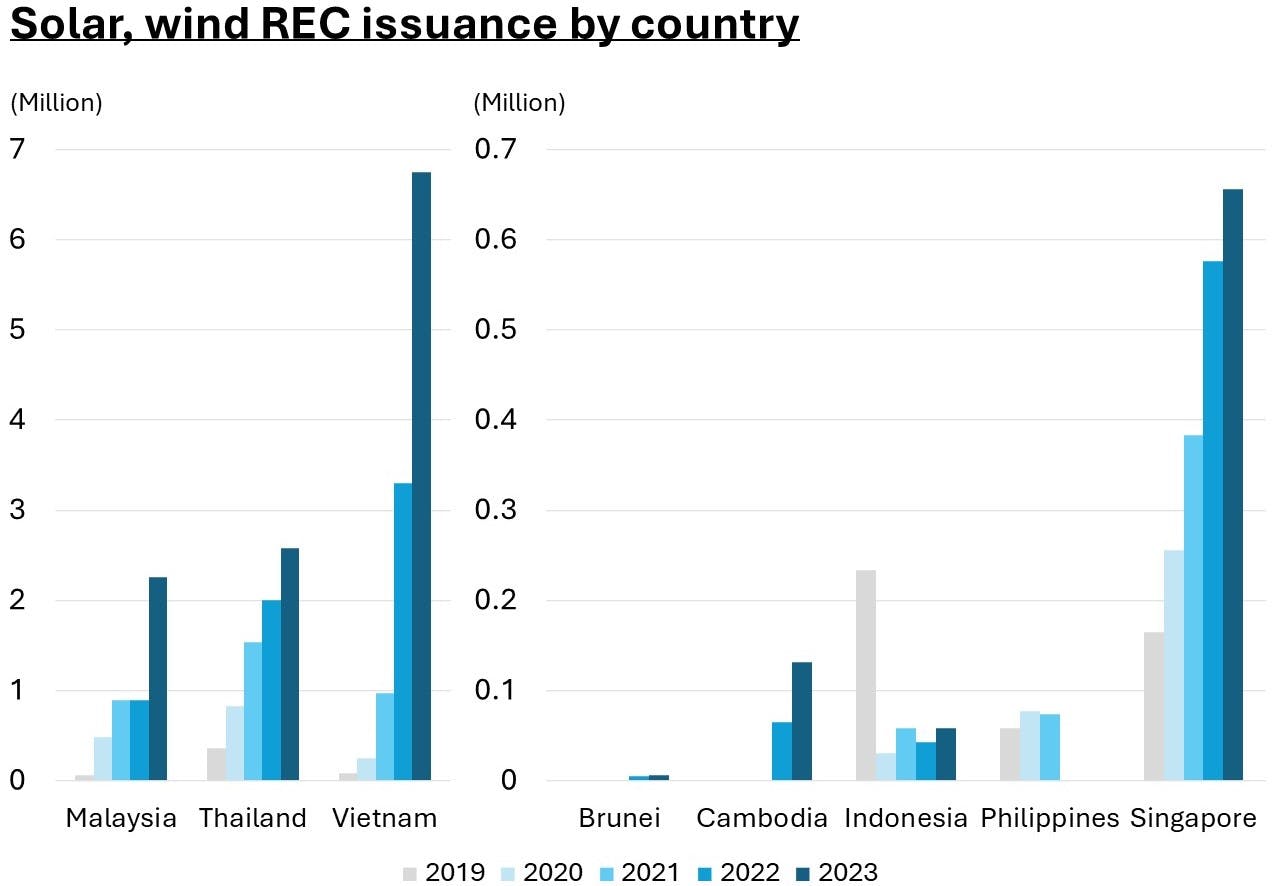

Eco-Business graph. Data: I-REC, TIGR registries.

In Southeast Asia, developers in Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam issue the most RECs – with Vietnamese players alone generating almost 7 million RECs last year. Singapore is also a growing player, though output from the city-state is a magnitude lower. The Philippines effectively left global RECs platforms to avoid double-counting after the country started a national compliance market in 2021.

Brunei and Cambodia are fledging markets, having only issued their first solar and wind RECs in 2022. Solar and wind players from Laos and Myanmar have not dabbled in RECs markets yet.

Prices vary drastically. According to global RECs trader Monsoon Carbon, solar certificates fetch as little as US$0.70 a piece in the oversupplied Vietnam market, and up to US$65 in Singapore, where corporate procurement appetite outstrips rooftop solar installations. Solar RECs in Indonesia average US$3, Malaysia US$5, while solar and wind RECs in Thailand go at about US$2, Monsoon Carbon founder and director Angus McEwin told Eco-Business.

Limited but growing appeal

For the most part, Southeast Asian renewable energy players are not relying on RECs to survive. McEwin said that the certificates provide under 10 per cent of electricity sales revenue in most markets – Singapore is one of few exceptions where RECs revenue is relatively high compared to electricity sales. However, the calculus could change in the future.

“As everybody starts doing something about renewable energy, and buyers start purchasing RECs, demand will increase, and prices will need to increase. And that means that the reward for the renewable energy developers will become more significant,” McEwin said.

The reward could differ by project type too – with rooftop projects that miss out on the economies of scale of large solar and wind farms having more to gain.

“For large-scale industrial businesses that need 10, 20 megawatts behind-the-meter [solar power] generation, the ability to unbundle RECs and sell them might be an interesting way to finance projects,” said Nitin Apte, chief executive of regional wind, solar and battery storage firm Vena Energy.

Vena Energy generally sells electricity and RECs bundled together, Apte said. This method usually involves fixed, longer-term contracts rather than the spot-market nature of I-REC and TIGR transactions. Unbundling RECs exposes sellers to additional price fluctuations, Apte noted.

Edwin Widjonarko, co-founder and technology director of Indonesian solar energy developer Xurya, which focuses on rooftop projects, said its income from REC sales, since 2021, is “supplemental”.

Widjonarko said RECs help projects get off the ground in new markets, where supply chain and talent shortfalls increase capital requirements.

“We wish we knew this earlier, such as back in 2018, when it would have been super helpful to us,” he added. Xurya now has 165 projects across Indonesia.

Investors are also getting into the game, with RECs “definitely a factor” in new financing decisions, as funders want to secure the offtake of new certificates, McEwin said.

There appears to be room for further growth in REC issuances in Southeast Asia: the 12.5 million volume last year – representing 12.5 terawatt-hours (TWh) of solar and wind power generation – is a fraction of the total 50 TWh produced in the region in 2022, according to analyst Ember.

Imperfect solution

Although RECs help wind and solar energy developers, critics say it supports overblown environmental claims by buyers. A 2022 study found that a group of 115 companies reported a 30-plus per cent reduction in “Scope 2” emissions – from electricity use – between 2015 and 2019, though the figure drops to under 10 per cent when RECs are excluded.

In theory, the environmental benefit from green power production already contributes to lowering the grid emissions factor on the local power network, so additional emissions reductions claimed by firms buying RECs, but not using the power, could amount to over-counting. RECs also do not strictly adhere to the carbon market’s core principle of “additionality” – that emissions reductions happen only because of revenue from certificate sales – since in most instances economically viable power generation precedes REC issuance.

Proponents of RECs say the increased cash flow to renewable energy developers will nonetheless spur growth. There have been moves to tighten regulations around the trade – global corporate RE100 initiative calls for RECs to be bought from power projects younger than 15 years. Standard-setter GHG Protocol asks companies buying RECs to report two Scope 2 figures: one factoring in the certificates, and one without.

There is also increasing consensus that RECs should only be sourced in the same market as where a company operates, to keep benefits local. Monsoon Carbon’s McEwin estimates 90 per cent of companies are already adopting this practice.

Within Southeast Asia, experts say RECs regulation could yet become more complicated with the rise of cross-border electricity trading, which raises the risk of double counting and possibly protectionist measures against unfavourable price swings. They say long-term financing for new solar and wind development via power purchase agreements remains key to the sectors’ growth.

For Xurya, beside RECs, “stable, clear and enforceable regulations” around corporate power deals will also be beneficial. “There are always changes in details every one or two years, which makes it a challenge for us to formulate power purchase agreements,” Widjonarko said.

But RECs could still play a viable role in the decarbonisation of the region. “RECs deal with the intermittent noise – you can purchase down to the megawatt-hour in principle. It deals with the variable component that longer-term agreements cannot buffer for,” said Dr David Broadstock, senior research fellow at National University of Singapore’s Sustainable and Green Finance Institute. More transparency around pricing will help stakeholders judge the utility of the market, he said.

“Until there is something better, this is the best solution. There is no other practical and simple way for most electricity consumers to source renewable energy,” McEwin said.