Carbon Brief analysis of figures in the International Energy Agency (IEA) electricity market report 2023 shows that renewables, combined with resurgent nuclear power, will more than cover growth in electricity demand between 2022 and 2025.

This means clean-energy sources will start displacing fossil fuels. As a result, global power-sector carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions will plateau or decline, despite rapidly rising demand.

Below, Carbon Brief runs through the report’s key findings via five charts.

Electricity demand

The IEA notes that global GDP growth projections have been revised down for almost every country due to the energy crisis, with the UK taking a particularly big hit.

Nevertheless, it says that global electricity demand growth will rebound strongly in 2023. It says another 2,500 terawatt hours (TWh) of demand will be added by 2025, predominantly in Asia.

This 9 per cent growth would take overall demand to 29,281TWh. It is equivalent to adding an EU-sized chunk of demand to the global electricity system – in only three years.

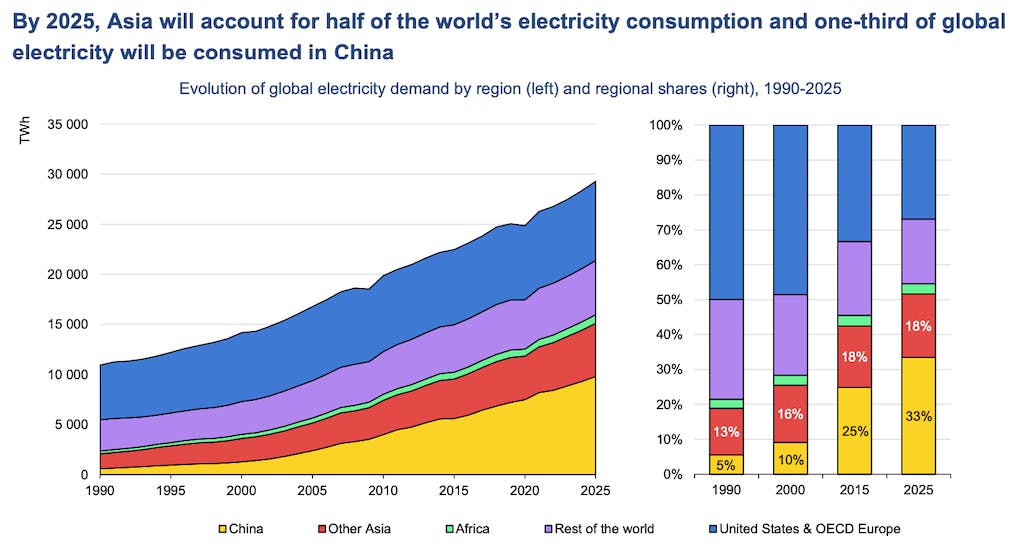

The IEA says growth will be concentrated in Asia, as shown in the chart below.

By 2025, China will account for a third of global electricity demand, up from 5 per cent in 1990 and 25 per cent in 2015. Combined with strong growth in other parts of Asia, by 2025 the region will make up more than half of global electricity demand, the IEA says, “for the first time in history”.

Left: Global electricity demand by region 1990-2025, terawatt hours. Right: Share of demand in selected years, per cent. Source: IEA electricity market report 2023.

Although electricity use will grow steadily in Europe and North America, their share of global demand will decline as Asia’s expands.

Renewable growth

The IEA goes on to say that renewables and nuclear will “dominate” electricity demand growth:

“Renewables and nuclear energy will dominate the growth of global electricity supply over the next three years, together meeting on average more than 90 per cent of the additional demand.”

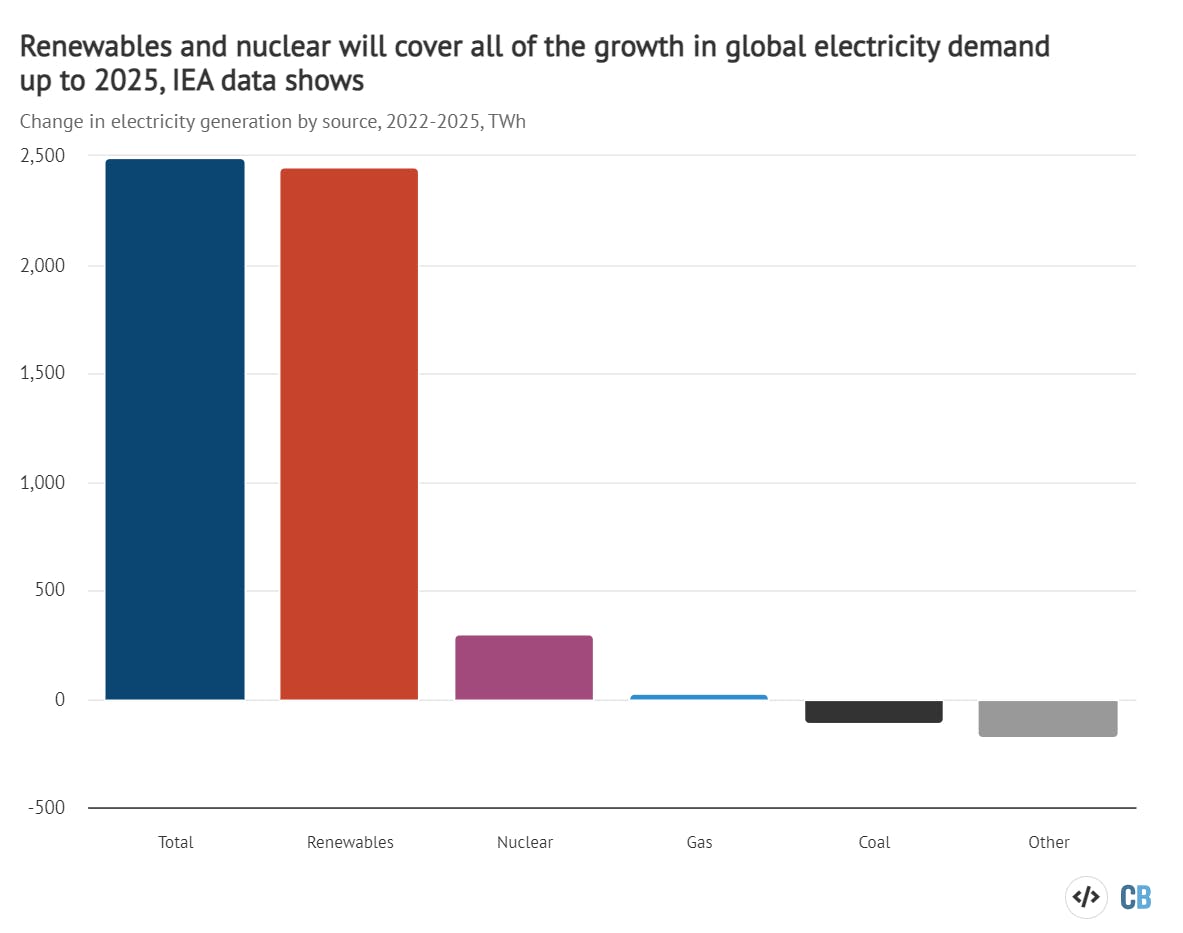

In aggregate, the picture is even more stark. Carbon Brief analysis of the IEA figures shows that it expects global electricity generation to rise by 2,493TWh between 2022 and 2025.

The IEA expects the growth in renewable generation to cover the vast majority of this total, growing by 2,450TWh. This is equivalent to 98 per cent of the overall increase in global demand.

Moreover, the IEA also expects a resurgence in nuclear generation, led by Asia. New construction in China and India, along with reactor restarts in France and Japan, will see nuclear output growing 302TWh by 2025.

In combination, these figures show that clean energy sources will outpace growth in global electricity demand, squeezing out fossil fuels in the process. The growth in generation by fuel is shown in the chart below, with renewables (red) nearly matching the total increase (blue).

Change in global electricity generation by source, 2022-2025, terawatt hours. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of IEA figures. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

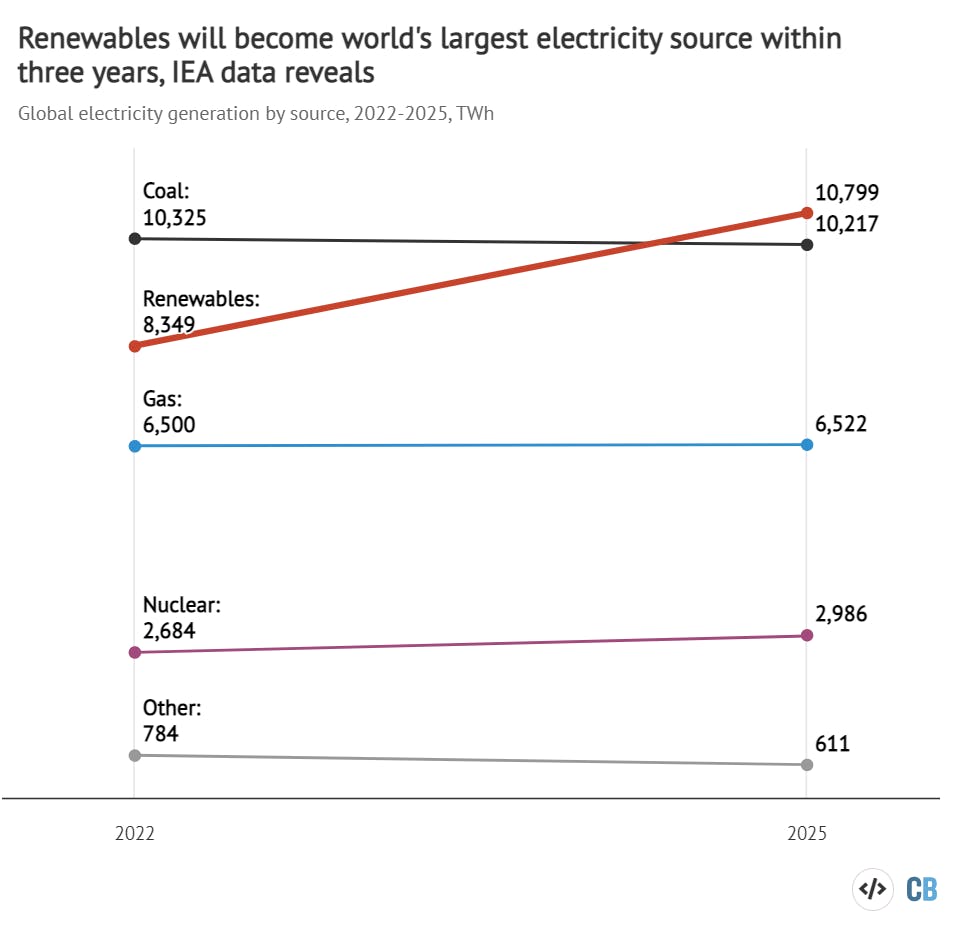

Growth in output over the next few years mean that renewables will overtake coal to become the world’s largest source of electricity within three years, the IEA data shows. This is illustrated in the chart below.

Global electricity generation by source in 2022 and 2025, terawatt hours. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of IEA figures. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Renewables would increase their share of global electricity generation from 29 per cent to 35 per cent within just three years.

Renewables had provided 20 per cent of the world’s electricity supplies in 1990 – and this share had remained more or less unchanged until as recently as 2010.

Coal’s share has already fallen from 40 per cent of global electricity generation in 2010 to 36 per cent today and would further decline to 33 per cent in 2025, the IEA figures show.

Nevertheless, the dirtiest fossil fuel would remain one of the world’s largest sources of electricity. Gas would generate 21 per cent of electricity in 2025 and nuclear 10 per cent.

Power plateau

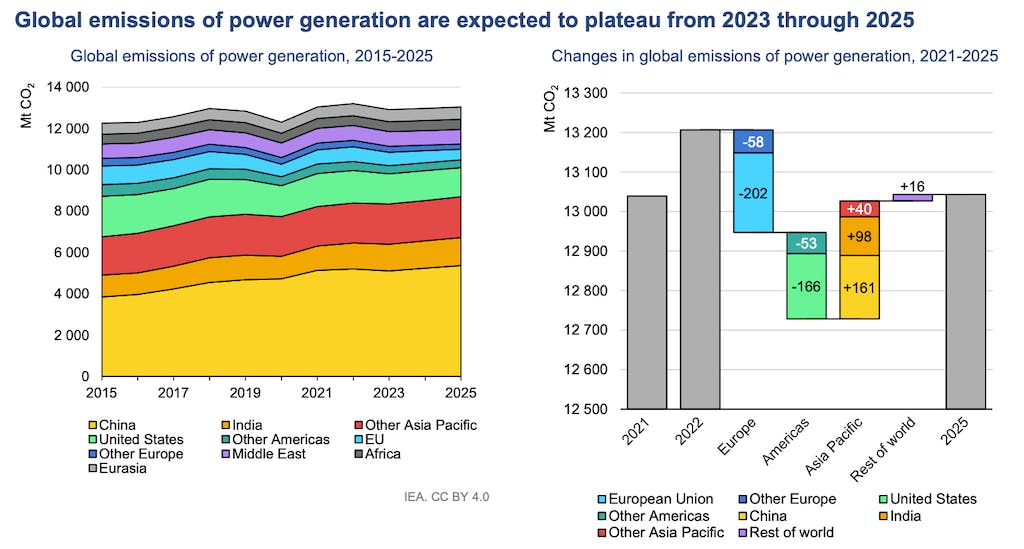

The clean-energy squeeze on fossil fuel electricity generation means that power-sector CO2 emissions will plateau, the IEA says, shown in the chart below (left).

In fact, its detailed figures suggest a marginal decline in power-sector CO2 emissions by 2025 (below right). Reductions in Europe (blues) and the Americas (greens) would more than offset increases in Asia Pacific (yellow, red and orange).

Left: Power sector CO2 emissions by region 2015-2025, millions of tonnes. Right: Changes during 2022-2025. Source: IEA electricity market report 2023.

It is worth emphasising, however, that power-sector emissions reached a record high in 2022, according to the IEA. This means that emissions would remain at – or only slightly below – their record high for the next few years, rather than starting to rapidly decline.

This IEA forecast is in line with one outlined by the Rocky Mountain Institute earlier this year. It said the world had reached peak fossil fuels for electricity generation, thanks to the accelerating growth of wind and solar power. The institute went on to forecast declines in fossil-fuel generation of 4 per cent per year from 2025 through to 2030.

Challenges ahead

The IEA notes that there will be challenges as wind and solar supply increasingly large shares of the world’s electricity. It says that electricity supply and demand are also becoming increasingly weather-dependent, pointing to recent heatwaves, storms and droughts as examples.

This points to the need for increasing demand-side flexibility from customers and expanding storage capacity, the IEA says. It also says sufficient “dispatchable” capacity will be needed, which can be switched on or off at will. The report says:

“In a decarbonised electricity sector, dispatchable renewables, such as hydro reservoir, geothermal and biomass plants, will be essential for complementing the variable renewables [wind and solar].”

Nonetheless, the report emphasises that the challenges of integrating variable renewables is currently no barrier to their expansion. It explains:

”[T]here is enough potential for further capacity expansions of variable renewables in many regions of the world without facing major system integration bottlenecks.”

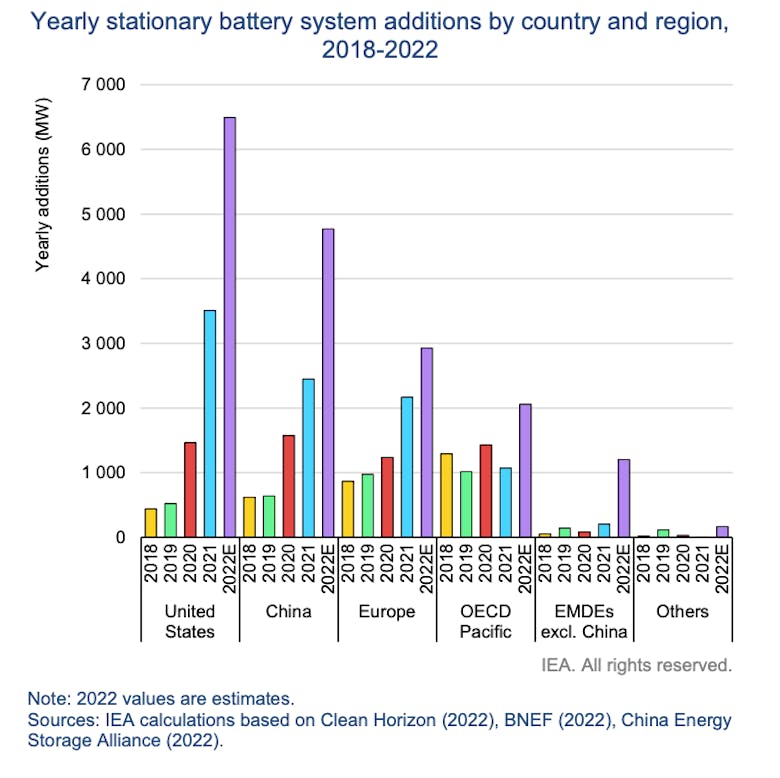

Relatedly, the report notes that more and more battery storage systems are being built each year. In aggregate, around 17 gigawatts (GW, thousand megawatts, MW) of new battery capacity was added in 2022, as shown in the figure below. This is up by around 90 per cent from a year earlier.

Within that global picture, the IEA says the growth of battery additions grew by 80 per cent in the US,

100 per cent in China, 35 per cent in the EU and roughly sixfold (~500 per cent) in emerging economies outside China.

Annual additions of battery storage capacity by region, megawatts. Source: IEA electricity market report 2023.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.