The new study develops the idea of “planetary boundaries“, first set out in an influential 2009 paper. The paper had defined a set of interlinked thresholds that it said would ensure a “safe operating space for humanity”. Its authors had warned that crossing these thresholds “could have disastrous consequences”.

The concept has been widely used in academia and policy spaces, but has also attracted criticism from scientists who say it oversimplifies a complex system, or could spread political will too thinly.

The new study – published in Nature and written by many of the same authors – gives the concept an important update by introducing a “justice” framework.

This includes “rejecting human exceptionalism” by focusing on all species and ecosystems, emphasising intergenerational justice and examining local-scale impacts.

The authors find that adding “justice considerations” often makes the planetary boundaries stricter, warning that seven of the eight “safe and just” global Earth-system limits have already been breached.

“There is no safe planet without justice,” a study author says. She explains that the new thresholds “define the environmental conditions needed not only for the planet to remain stable, but to enable societies, economies and ecosystems across the globe to thrive”.

However, a researcher not involved in the study warns against allowing a “self-selected group of scientists” to define the planetary “safe space”.

He tells Carbon Brief that this approach is “divisive and not the way to address the global challenges of the Anthropocene”.

‘Planetary boundaries’

Human activity puts pressure on the Earth in a range of ways, from surface warming to biodiversity loss. In 2009, a team of scientists set out to quantify how much humans can use the Earth’s resources without putting themselves and the planet in danger.

The team – led by Prof Johan Rockström, now the joint director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research – published a landmark paper in 2009. The paper identifies nine interlinked global systems and sets a “planetary boundary” for each. Staying within all of those limits ensures a “safe operating space for humanity”, the study claims.

“

This kind of unilateral ‘scientific’/expert setting of limits – environmental or social – is divisive and not the way to address the global challenges of the Anthropocene, which can only succeed through increasing cooperation, trust and negotiations across all concerned.

Prof Erle Ellis, researcher, University of Maryland

The 2009 work has been cited widely in academia, including in a key report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, forms the cornerstone for a theory of economic development known as “doughnut economics” and was featured in a 2021 Netflix documentary starring Rockström alongside Sir David Attenborough.

But the framework has also attracted criticism.

Prof Simon Lewis, a global change scientist at University College London and the University of Leeds, wrote a commentary piece at the time calling the idea “conceptually brilliant and politically seductive”, but warning that “boundaries could spread political will thinly”, adding that the will to act “is already weak”.

In response to the original paper, Prof Ruth DeFries, the co-founding dean of the Columbia Climate School, led a study on “planetary opportunities” – emphasising the ability of societies to adapt to changing conditions. DeFries, who was not involved in the 2009 study or the new paper, tells Carbon Brief:

“We wrote the ‘planetary opportunities’ paper to counter the idea that there is a hard and fast global-scale limit to the use of resources, without regard for the ability of societies to adapt to change or overcome negative externalities of technologies.”

An “updated and extended analysis” of the planetary-boundaries framework was published in 2015. The authors identified climate change and biosphere integrity as “core” boundaries, stating that either has the potential on its own to “drive the Earth system into a new state”, if breached.

In 2017, Dr Jose Montoya – a senior scientist at France’s Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique – published a critique of the planetary boundaries concept, arguing that “the notion of a ‘safe operating space for biodiversity’ is vague and encourages harmful policies”.

Rockström and his team called the piece “a vitriolic and highly opinionated critique of the planetary boundaries framework based on a fundamental misrepresentation of the framework”.

‘Safe and just’

In 2019, Rockström co-founded the Earth Commission – an international team of natural and social scientists – to advance the planetary boundaries framework.

Since then, the team focused on improving “justice and equity”, as well as establishing “quantitative scientific targets from the local to the global scale” and “the ability to translate the science into operational implementation on the ground”, Rockström told a press briefing on the new study.

Now, more than a decade after planetary boundaries were first proposed, the updated Earth-system boundaries framework explores how to keep the planet stable while minimising “significant harm” to humans and other species, using a “justice framework”.

The authors select five of the nine original planetary systems – climate, biosphere, water, nutrients and air pollution – and identify eight key, quantifiable indicators that can monitor these systems.

These indicators – including warming level, area of natural ecosystems and surface-water flow – were “carefully chosen” to be “implementable for stakeholders in cities, businesses, countries across the world”, Rockström told a press briefing.

For each indicator, the authors assess the conditions needed to avoid “significant harm” at both global and local scales, taking into account the following justice considerations:

An “updated and extended analysis” of the planetary-boundaries framework was published in 2015. The authors identified climate change and biosphere integrity as “core” boundaries, stating that either has the potential on its own to “drive the Earth system into a new state”, if breached.

In 2017, Dr Jose Montoya – a senior scientist at France’s Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique – published a critique of the planetary boundaries concept, arguing that “the notion of a ‘safe operating space for biodiversity’ is vague and encourages harmful policies”.

Rockström and his team called the piece “a vitriolic and highly opinionated critique of the planetary boundaries framework based on a fundamental misrepresentation of the framework”.

‘Safe and just’

In 2019, Rockström co-founded the Earth Commission – an international team of natural and social scientists – to advance the planetary boundaries framework.

Since then, the team focused on improving “justice and equity”, as well as establishing “quantitative scientific targets from the local to the global scale” and “the ability to translate the science into operational implementation on the ground”, Rockström told a press briefing on the new study.

Now, more than a decade after planetary boundaries were first proposed, the updated Earth-system boundaries framework explores how to keep the planet stable while minimising “significant harm” to humans and other species, using a “justice framework”.

The authors select five of the nine original planetary systems – climate, biosphere, water, nutrients and air pollution – and identify eight key, quantifiable indicators that can monitor these systems.

These indicators – including warming level, area of natural ecosystems and surface-water flow – were “carefully chosen” to be “implementable for stakeholders in cities, businesses, countries across the world”, Rockström told a press briefing.

For each indicator, the authors assess the conditions needed to avoid “significant harm” at both global and local scales, taking into account the following justice considerations:

- Interspecies justice: prioritising other species and ecosystems in addition to humanity.

- Intergenerational justice: considering how actions taken today will impact future generations.

- Intragenerational justice: accounting for factors including race, class and gender, which “underpin inequality, vulnerability and the capacity to respond” to changes in planetary systems.

The paper defines significant harm as “severe existential or irreversible negative impacts on countries, communities and individuals”.

(The challenging and subjective nature of summarising complex, geographically variable risks into single, global thresholds is at the heart of much of the criticism of the planetary boundaries concept.)

“There is obviously no one way to quantify justice,” says Dr Steve Lade, a researcher at the Stockholm Resilience Centre who is an author on the new study. He tells Carbon Brief that this paper looks at exposure to “significant harm”, but notes that other studies by members of the team have delved into other aspects of justice, such as access to resources.

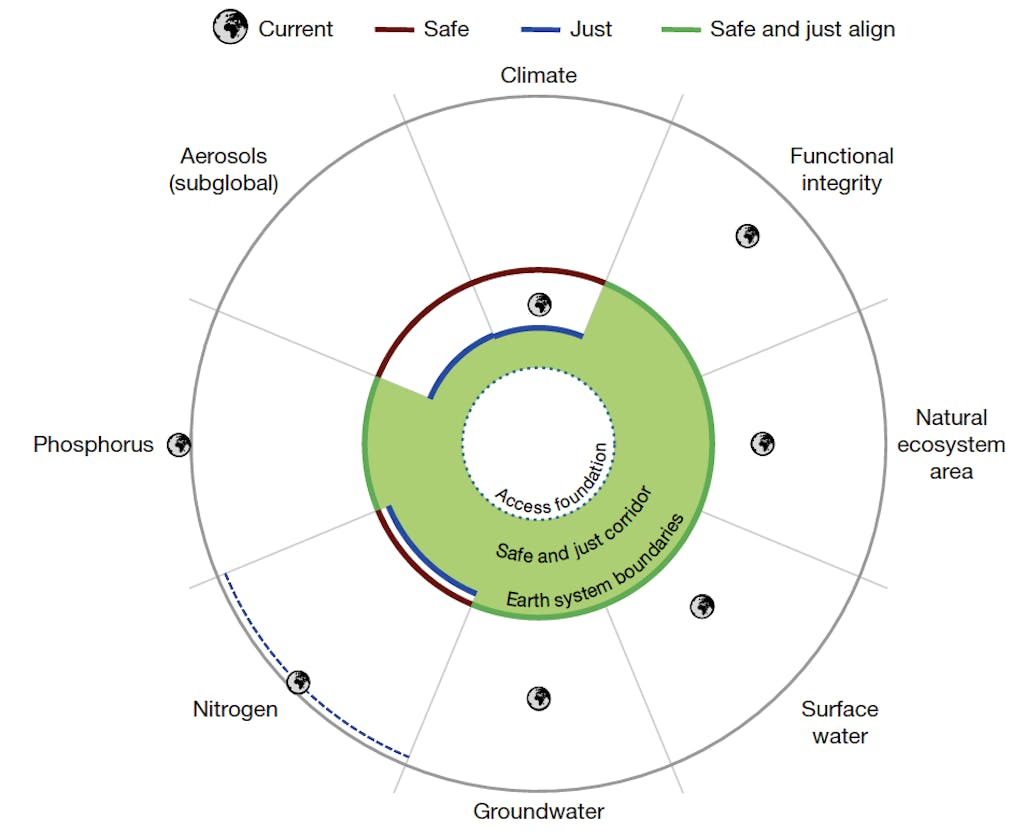

The graphic below shows the eight global Earth-system boundaries proposed in the study. The red and blue lines show the “safe” and “just” boundaries, respectively. The green shading shows where the safe and just boundaries align. The icons of the Earth show the state of the planet today. Where this image sits outside of the red, blue and green circles, the global Earth-system boundary has already been breached, according to the researchers.

The eight Earth-system boundaries proposed in the study: climate; functional integrity of the biosphere; natural-ecosystem area; surface-water flows; groundwater levels; nutrient cycles for nitrogen; phosphorus; and atmospheric aerosol levels. Red lines show the “safe” boundaries, while the blue lines show the “just” boundaries. The green shading shows where the safe and just boundaries align. The icon of the Earth shows the state of the planet today. Source: Rockström et al. (2023)

The authors find that adding “justice considerations” makes many of their boundaries more strict. As a result, seven of the eight “safe and just” global Earth-system boundaries have already been breached.

(Looking at “safe” boundaries alone, six of eight have already been breached, but the Earth’s climate currently remains within the “safe” threshold, according to the paper.)

Prof Joyeeta Gupta, a professor of environment and development at the University of Amsterdam and co-founder of the Earth Commission, is an author on the new study. She told a press briefing that “there is no safe planet without justice”.

She said the new thresholds “define the environmental conditions needed not only for the planet to remain stable, but to enable societies, economies and ecosystems across the globe to thrive”.

Boundaries breached

Climate change is the first Earth-system boundary discussed in depth in the paper. It is the only one with a “relatively well-established and implemented methodology”, the authors write.

The authors find that a global warming level of 1C above pre-industrial levels exposes tens of millions of people to temperature “extremes” – defined as wet bulb temperatures of greater than 35C for at least one day per year.

They warn that, at 1.5C, more than 200 million people – disproportionately those already vulnerable, poor and marginalised – could be exposed to “unprecedented” average annual temperatures.

The paper proposes a “safe” surface warming boundary of 1.5C and a “safe and just” boundary of 1C. The planet has already warmed by 1.2C, on average, meaning that the “safe and just” boundary has already been breached.

This study is the first to assess Earth-system boundaries at a local scale, rather than analysing the planet as a whole. This allows the authors to determine which boundaries have been crossed in specific regions and to identify “hotspots” for breached boundaries.

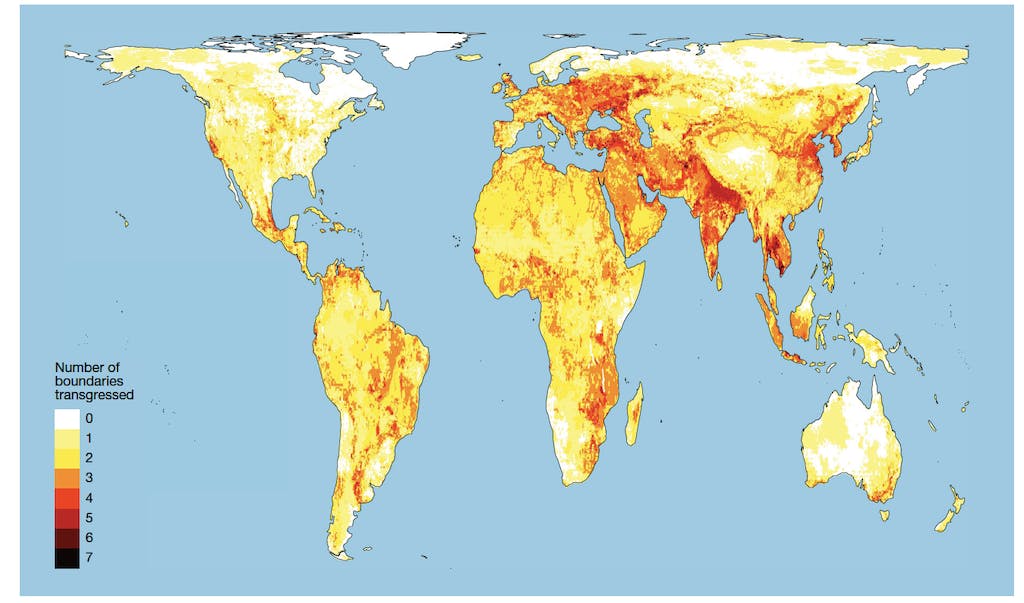

The map below shows the number of Earth-system boundaries that have already been breached in different regions, where darker colours indicate more boundaries breached.

The number of Earth-system boundaries already breached in different regions, with lighter colours indicating fewer boundaries passed and darker colours indicating more thresholds exceeded. Source: Rockström et al. (2023)

The authors find that two or more “safe and just” earth system boundaries have been breached across 52 per cent of the world’s land surface, affecting 86 per cent of the global population.

Reception

Carbon Brief spoke to a range of scientists about the new study.

Dr Åsa Persson, research director at the Stockholm Environment Institute, is an author on the 2009 paper, but was not involved in the new study. She tells Carbon Brief that the new study is a “significant scientific contribution”. She adds:

“I commend the authors for not oversimplifying justice, but considering its many dimensions in a nuanced, yet workable way.”

However, she says that in her view, “some questions on interdependencies between boundaries remain unanswered”.

DeFries tells Carbon Brief that the focus on localised impacts makes the new study more “nuanced” than the 2009 paper. She adds that the planetary-boundary concept is “intuitively appealing”, but warns that the complexity of the Earth system “makes the task of defining a limit extremely difficult”.

Dr Jose Montoya is very critical of the new framework, saying the scientific basis is “weak”. He maintains that “there are no safe operating spaces”, telling Carbon Brief:

“Even small disturbances can have very large effects on ecosystems at different scales.”

Prof Frank Biermann – a professor of global sustainability governance at Utrecht University, who was not involved in the study – conducted a “critical appraisal” of the planetary boundaries concept in 2020.

Biermann welcomes that the paper now seeks to address questions of global justice. However, he tells Carbon Brief that he feels the “definitions of justice and societal values” presented by the authors “in essence, belong in the political space”.

Prof Erle Ellis from the University of Maryland co-authored the planetary opportunity paper with DeFries. He tells Carbon Brief that he appreciates the inclusion of social justice in this “expanded and more nuanced framework”. However, he says there are “issues relating to the way this work was produced”.

He continues:

“The planetary boundaries framework originated with a self-selected group of scientists deciding what the ‘environmental safe space for humanity’ was – without any input from ‘humanity’.

“Now, after naming itself the ‘Earth Commission’, this small group will now also decide the planetary ‘safe space’ in terms of social justice?

“This kind of unilateral ‘scientific’/expert setting of limits – environmental or social – is divisive and not the way to address the global challenges of the Anthropocene, which can only succeed through increasing cooperation, trust and negotiations across all concerned.”

Study author Gupta tells Carbon Brief about the importance of “procedural justice” in interpreting these results. She says:

“Procedural justice requires these numbers to be talked about and debated, and if people come up with better numbers, or better suggestions, then we’re open to their critique.

“This is just a proposal about safe and just boundaries. And it remains to be debated in the political sphere before it’s adopted…We are not dictating anything to anybody.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.