The oil major has “updated” its target to cut the total “net carbon intensity” of all the energy products it sells to customers – the emissions per unit of energy – by 20 per cent between 2016 and 2030. The reduction is now set at between 15-20 per cent.

Within Shell’s strategy, chief executive, Wael Sawan, writes that this change reflects “a strategic shift” to focus less on selling electricity, including renewable power.

Instead, the company says investment in oil and gas “will be needed” due to sustained demand for fossil fuels. It emphasises the importance of liquified natural gas (LNG) as “critical” for the energy transition and says it will grow its LNG business by up to 30 per cent by 2030.

This amounts to a bet against the world meeting its climate goals, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) and others concluding no new oil-and-gas investment is needed on a pathway to 1.5C – and warning against the risk of “overinvestment”.

Elsewhere in the report, Shell notes that it has “chosen to retire [its] 2035 target of a 45 per cent reduction in net carbon intensity” due to “uncertainty in the pace of change in the energy transition”.

Both goals were intended as stepping stones on the company’s journey towards net-zero emissions by 2050, a goal set by the previous chief executive, Ben van Beurden, in 2020.

The weakening of climate goals from Shell, the world’s second-largest investor-owned oil-and-gas company, comes after BP scaled back its ambitions last year.

“

Our ability to raise and invest capital depends on delivering strong returns to shareholders, shaping the role that Shell can play on the journey to net-zero. We believe this focus makes it more, not less, likely that we will achieve our climate targets and ambitions.

Wael Sawan, CEO, Shell

Weaker targets

The new report marks the first three-year review of Shell’s “energy transition plan”, after it was adopted in 2021.

Rather than setting a target for cutting its entire “scope 3” emissions – those generated by the use of Shell’s fossil fuels and other energy products by consumers – the company set itself “net carbon intensity” targets on its path to net-zero.

This allows Shell to bring down its carbon intensity and hit its targets through means other than cutting its oil-and-gas production, such as selling more low-carbon products, including renewable electricity.

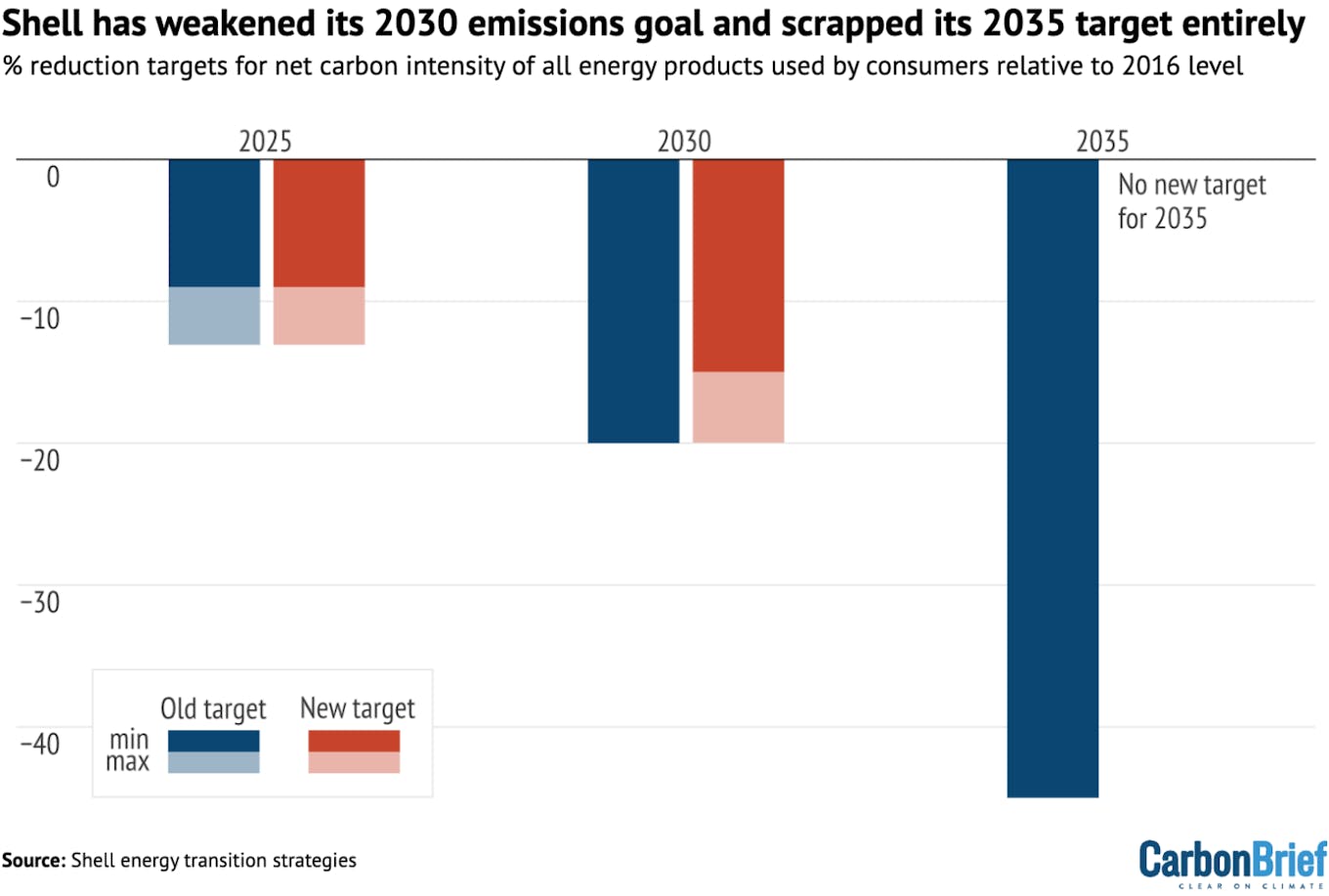

Shell initially said the carbon intensity of the energy it sells would fall 20 per cent by 2030, from a baseline of 2016, and then 45 per cent by 2035.

This amounted to a cut from 79g of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule of energy (gCO2e/MJ) to 63gCO2e/MJ by 2030 and 43gCO2e/MJ by 2035.

As the chart below shows, these targets have now been weakened. The 2030 target has been changed to a range of 15-20 per cent and the 2035 target has been “retired”, according to a footnote in the review.

Targets to reduce the net carbon intensity of Shell’s energy product sales, per cent below 2016 levels, including old targets (blue) and new ones (red). Targets given as a range are indicated by pale colours. Source: Shell energy transition strategies.

Shell attributes these changes to a shift in its business priorities.

The firm says that when it comes to selling electricity, including renewable power, it will focus on “value over volume”. For example, it will target “commercial customers more than retail customers”.

The company points to its withdrawal from supplying energy to European homes, having closed its utilities arms in the UK, the Netherlands and Germany in 2023.

Nevertheless, the company also says the “biggest driver for reducing our net carbon intensity is increasing the sales of and demand for low-carbon energy”, rather than cuts in fossil-fuels production. The report states that:

“Investment in oil and gas will be needed because demand for oil and gas is expected to drop at a slower rate than the natural decline rate of the world’s oil and gas fields, which is 4-5 per cent a year.”

This amounts to a bet against the world meeting its carbon targets. If the world were to get on track to limiting warming to 1.5C, there would be no need for investments in new oil and gas production, according to the IEA.

In its 2023 World Energy Outlook, the IEA said that warnings from oil and gas producers that the world was “underinvesting” in new supplies were no longer valid. It said:

“[T]he fears expressed by some large resource-holders and certain oil and gas companies that the world is underinvesting in oil and gas supply are no longer based on the latest technology and market trends.”

The agency added that risks were “weighted more towards overinvestment”.

LNG over oil

Shell has also introduced a new target for cutting emissions from customer use of its oil products, such as petrol and diesel used in cars, within its energy transition strategy review.

This goal amounts to a 40 per cent reduction in absolute emissions by 2030, compared to 2016 – a level the European company says is compatible with the EU’s climate targets for transport. Shell says it will “gradually reduc[e] exposure to oil products used for transport”, by shifting its sales away from this area.

Alongside this, Shell announced a renewed focus on LNG in the strategy, which it says will play a “critical role” in the energy transition, even as people embrace electric cars and therefore reduce their reliance on oil.

The company expects global demand for LNG to continue growing “at least through the 2030s”, and says it will grow its LNG business by 20-30 per cent by 2030.

This marks a continuation of Shell’s focus on LNG from its 2021 strategy, when it said it would “extend leadership” in this area.

Shell’s internal outlook for the growth of global LNG demand is markedly more optimistic than the IEA’s, which suggests that there is already enough capacity built or under construction to meet demand for the next two decades.

According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), Shell’s LNG outlook “underestimates barriers” to demand growth. IEEFA says:

“[Shell] is pinning its hopes on rapid demand growth in emerging markets and China’s industrial sector, which may never materialise.”

Despite its plans to expand its LNG business, Shell’s report overall emphasises a “balanced and orderly transition away from fossil fuels”.

Wider trends

Shell states that it has so far met its climate targets and points to its success reducing emissions from its own operations, such as those from oil rigs and offices.

It argues in the small print at the bottom of the report that, despite its targets for consumer carbon intensity, “Shell only controls its own emissions”.

(Shell has long maintained this line, that it is merely meeting the demand of customers to buy fossil fuels. Exxon chief executive Darren Woods recently made a similar argument.)

The report also stresses that its plans for net-zero are dependent on society as a whole and “if society is not net-zero in 2050… there would be significant risk that Shell may not meet this target”. This is familiar language from the oil major, which frequently explains that it is consumers, not Shell itself, that influence fossil-fuel use.

Shell’s review follows the global energy crisis that has unfolded over recent years, driven by spiralling gas prices. In response to the changing energy landscape this has brought about, there has been a shift in tone from the oil majors regarding climate commitments.

It also follows a period in which companies such as Shell have made record profits due to rising fossil-fuel prices.

After taking over from Van Beurden, Shell chief executive Sawan stated that “cutting oil and gas production is not healthy”, emphasising the “fragility of the energy system”. In his introduction to the new strategy, Sawan writes:

“Our ability to raise and invest capital depends on delivering strong returns to shareholders, shaping the role that Shell can play on the journey to net-zero. We believe this focus makes it more, not less, likely that we will achieve our climate targets and ambitions.”

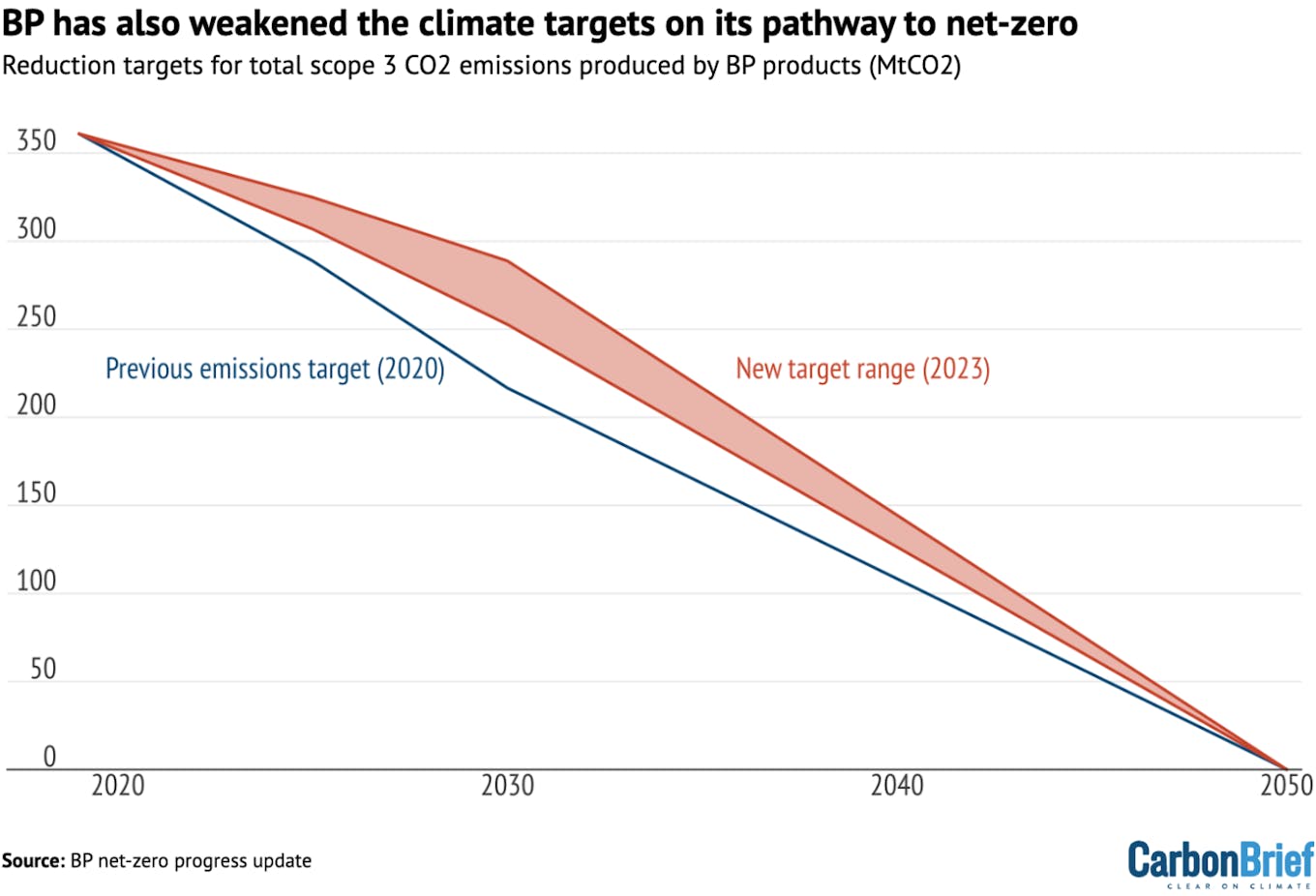

BP, Europe’s second largest oil major, weakened its climate targets last year. The change in its goals, which unlike Shell’s are based on full scope 3 emissions, can be seen in the chart below.

Reduction targets for total scope 3 CO2 emissions produced by BP products (million tonnes of CO2 - MtCO2). The old target is indicated by a blue line and the range of new targets is indicated by the red area. Source: BP net-zero progress update.

Shell’s “strategic shift” in its operational focus comes amid a wider effort to cut operating costs.

This has seen the company announce plans to reduce staff numbers, in particular in low-carbon sectors of the company such as hydrogen.

The company’s profits have fallen now fossil-fuel costs have returned to more normal levels, but have remained high. In February, the company announced an annual profit for 2023 of more than £22bn (US$28bn), one of its most profitable years on record.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.