The world is expected to get warmer much faster than previously expected without drastic moves to cut greenhouse gas pollution. Rising temperatures will lead to dangerous weather extremes and rising sea levels in the coming years, according to a new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), authored by the world’s leading climate scientists.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

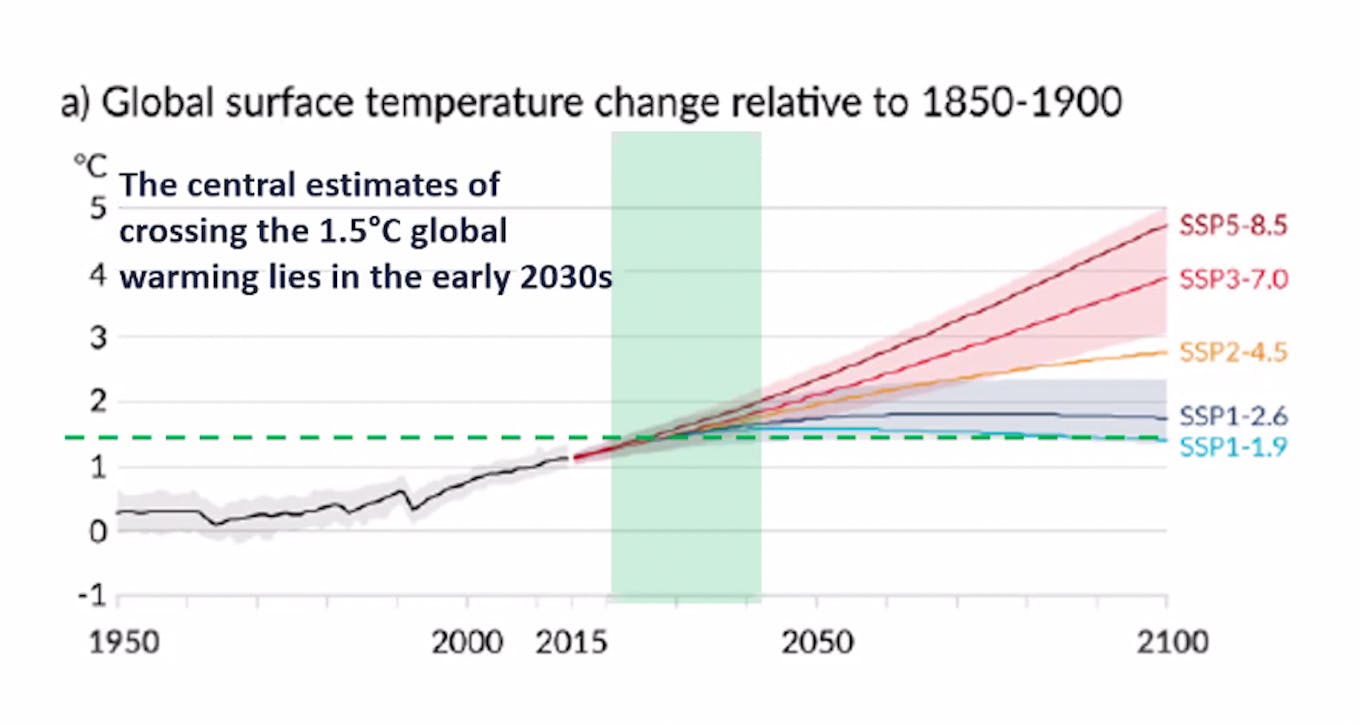

A global warming increase of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, a marker that world leaders pledged not to exceed this century when the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, could be reached by 2030 — possibly earlier — as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise despite widely-promised climate action by the world’s biggest carbon polluters.

The climate-critical 1.5 °C warming increase is expected to land a decade earlier than a prediction the IPCC made three years ago under all emissions scenarios.

The IPCC’s sixth assessment report (IPCC6AR) is the latest in a series of reports that assess the science of climate change, its impacts and risks.

The 3,949-page report is a “code red for humanity,” said Antonio Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations, in remarks appended to the release. “This report must sound a death knell for coal and fossil fuels before they destroy our planet.”

Five global warming scenarios from IPCC that depend on greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. All point to exceeding 1.5°C in the 2030s [click to enlarge]. Source: IPCC

Professor Benjamin Horton, a principal investigator at the Earth Observatory of Singapore at Nanyang Technological University and one of the report’s review editors, said that the findings are “unambiguous” on the dangers of global heating beyond 1.5°C, which he said will have “progressively serious, centuries’ long and, in some cases, irreversible consequences.”

The report predicts particularly stark consequences for Southeast Asia, one of the planet’s most vulnerable regions to climate change. The archipelagic regional bloc will be hit by rising sea levels, heat waves, drought, and more intense and frequent bouts of rain. Known as “rain bombs”, heavy rain events will intensify by seven per cent for each degree of global warming.

Although Southeast Asia is projected to warm slightly less than the global average, sea levels are rising faster than elsewhere, and shorelines are retreating in coastal areas where 450 million people live. Rising waters are projected to cost Asia’s major cities billions in damage this decade, according to a recent study, and the impact is amplified by tectonic shifts and the effects of groundwater withdrawal, Horton told Eco-Business.

Nineteen of the 25 cities most exposed to a one-metre sea-level rise are in Asia, seven in the Philippines alone. But sea levels could rise by much more — up to 15 metres by some estimates — if the polar ice sheets melt, a catastrophic climatic phenomenon known as a tipping point, which will set off a domino effect of other climate events.

“The threat of climate change is increasing, and it is increasing rapidly,” said Horton. “With many low-lying coastal cities exposed to sea-level rise and tropical cyclone risk, dramatic increases in heat and humidity expected across the region, and extreme precipitation forecast in some areas, but drought anticipated in others, Southeast Asian societies and economies will be increasingly vulnerable without adaptation and mitigation.”

Southeast Asia’s weak climate defence

IPCC’s report found that human activity was “unequivocally” to blame for increasingly harsh climate events such as heatwaves, floods and droughts, and achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, as outlined in the Paris Agreement, was necessary to limit warming to 1.5°C.

Though Southeast Asian nations are projected to suffer among the harshest effects of climate change, most of the region’s countries’ do not have carbon reduction strategies in place that will effectively mitigate the severity of the climate risks outlined by IPCC’s report.

Southeast Asia’s largest economy, Indonesia, plans to achieve net-zero by 2060, and though the country’ energy minister recently said it could easily hit this target, the country is still 60 per cent powered by coal, the single biggest driver of manmade emissions. Malaysia has said it will cut emissions intensity by 45 per cent by 2030, but also plans to ramp up its use of coal power.

Singapore, which has warmed 80 per cent faster than the rest of the region over the past 70 years, has said it will achieve net-zero emissions some time in the next half of the century, “as soon as it is viable”. Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines plan to set net-zero emissions targets ahead of COP26, a landmark climate change conference in November spearheaded by the United Nations.

To meet more ambitious climate targets, Southeast Asia’s developing nations are partly banking on climate finance to help them tackle a problem caused mainly by industrialised countries. In 2009, rich countries promised US$100 billion a year in funding by 2020 to help climate-vulnerable poorer nations tackle climate change, but a recent study shows that the pledged finance has not materialised.

“After years of limited action, many countries, pushed by a concerned public and corporations, seem willing to curb their carbon emissions. We are hopelessly unprepared to deal with increasingly severe extreme weather events, even though these have been predicted by the IPCC for decades,” Horton said.

Dr Stephen Cornelius, chief adviser on climate change and World Wide Fund for Nature’s (WWF) lead on the IPCC, commented that “every fraction of a degree of warming matters to limit the dangers of climate change.”

“It is clear that keeping global warming to 1.5°C is hugely challenging and can only be done if urgent action is taken globally to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect and restore nature,” he said.