Southeast Asia is home to about one in five species of wildlife on Earth. These species can be found in the lush forests of Indonesia and Malaysia, and among vibrant corals along the Philippine coast.

Whether these creatures still have a home in eight years’ time could make or break a pledge made on the world stage last month. At the COP15 biodiversity summit in Montreal, Canada, leaders of nearly 200 countries agreed to conserve 30 per cent of the Earth’s lands and seas by 2030. Priority is supposed to be on biodiversity-rich places.

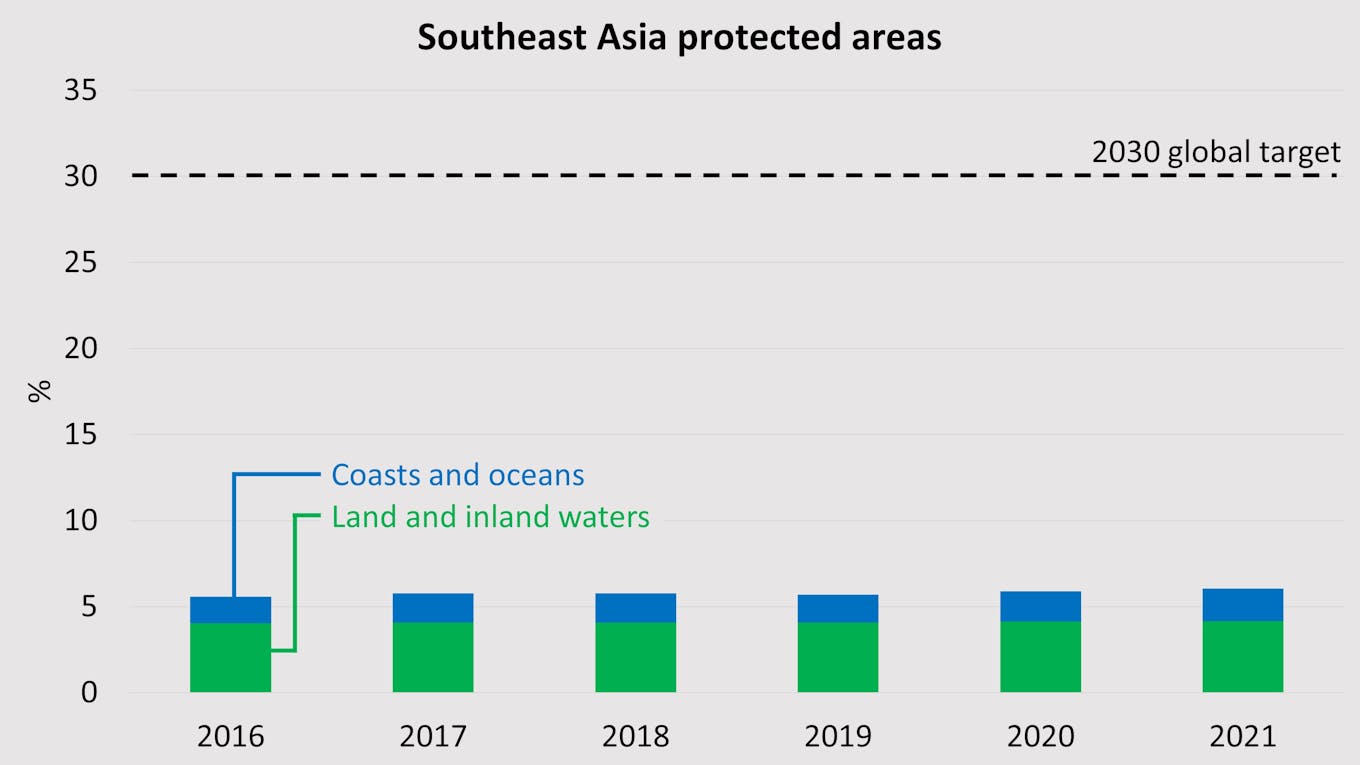

The 30 per cent target is a global goal, with no targets prescribed for each country or region. But using it as a reference against the latest data on nature protection in Southeast Asia makes clear the huge challenge the region faces, if it is to contribute meaningfully to the global target.

Data: World Database on Protected Areas, via Protected Planet.

According to data from the World Database on Protected Areas, a repository helmed by major conservation groups including the United Nations Environment Programme, just over 6 per cent of Southeast Asia’s land and territorial waters are currently protected. The figure has not changed significantly in at least the last six years, as the de-gazetting of protected areas largely offset any new parks and sanctuaries created.

This means that the total size of protected areas will have to buck the inertia and rise five-fold in eight years for Southeast Asia to cross the 30 per cent conservation milestone by 2030.

Data: World Database on Protected Areas, via Protected Planet.

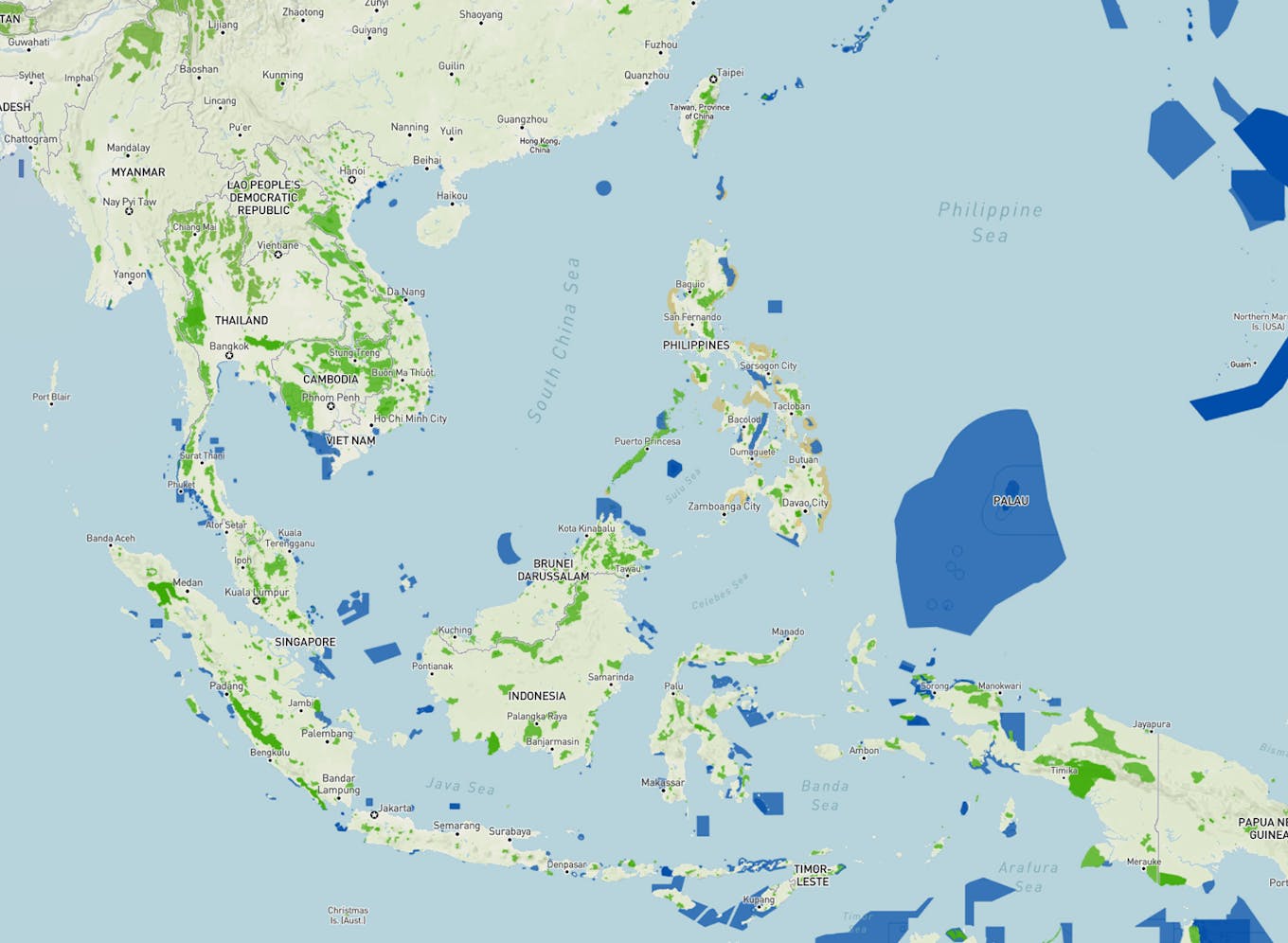

Protected nature areas in Southeast Asia and the western Pacific. Marine conservation sites are in blue; land-based ones are in green. Image: mapbox, via Protected Planet. [click to enlarge]

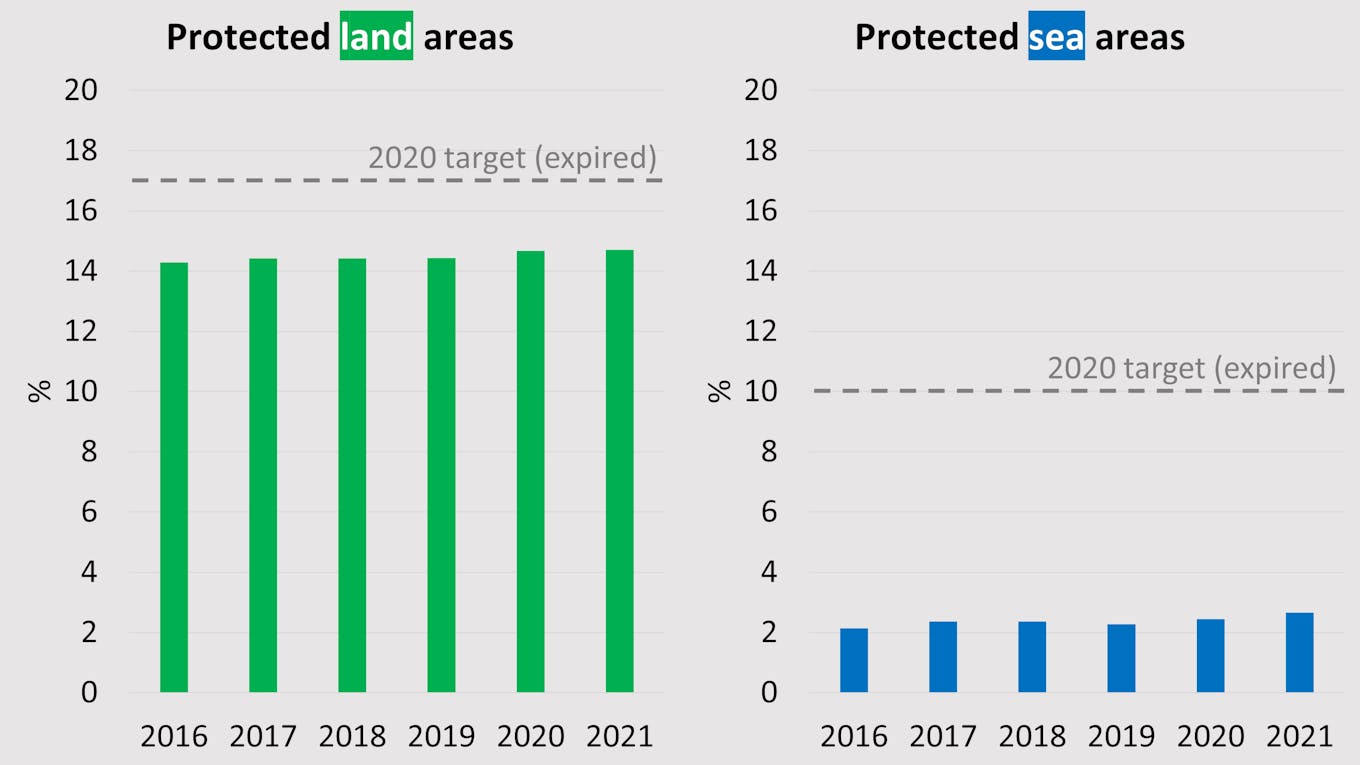

More land – 15 per cent of the total – is protected than seas – 3 per cent – in Southeast Asia. Such imbalance is a global trend. Open waters can be harder to patrol and enforce; the ocean territory of many countries is huge. But Southeast Asia’s conservation figures lag the global figures of 16 and 8 per cent for land and sea.

Southeast Asia’s marine conservation figure is especially low, even going by old standards. The global biodiversity goals of the last decade called for 10 per cent of the world’s oceans to be protected.

Indonesia, which houses the largest repository of coral reefs in the world, at around 50,000 square kilometres, protects about 3 per cent of its marine territories. The Philippines ranks third in the world for size of its coral reefs, but has less than 2 per cent of its waters protected.

Plans for new marine parks could be harder to implement because there are more conflicting interests out at sea, according to Surin Suksuwan, a conservation specialist from Malaysia. Countries may want to prioritise shipping lanes, as well as oil and gas exploration, Surin explained.

Some governments may also want to continue fishing operations in open waters.

“We don’t really depend on hunting of wild mammals on land, but we actually still depend, on a huge scale, on wild-caught marine fishes,” Surin said. He added that marine protected areas can serve as good spawning grounds and eventually increase fish yields, but not all governments take such a long-term view.

Nonetheless, there have been some big moves in recent years. Malaysia created its largest marine protected area, a 10,000 square kilometre stretch known as Luconia Shoals, off Borneo island in 2019. Indonesia cordoned off over 12,000 square kilometres of biodiversity-rich marine areas in its eastern Islands earlier this year.

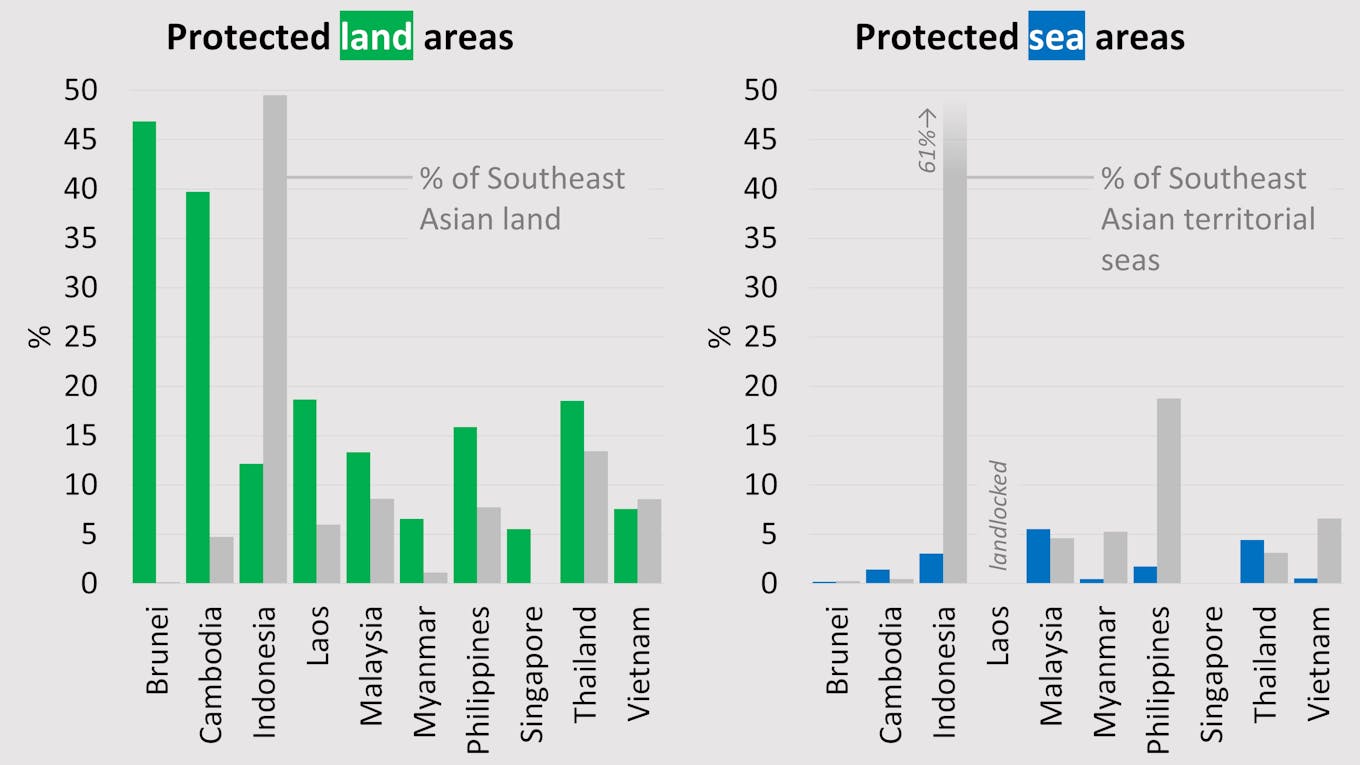

Data: World Database on Protected Areas, via Protected Planet. Data from 2021 is shown.

Only two Southeast Asian countries, Brunei and Cambodia, conserve over 30 per cent of their land. However, these are relatively small states, representing only about 5 per cent of Southeast Asia’s entire landmass.

Indonesia, the largest Southeast Asian country by a wide margin, conserves about 13 per cent of its land area.

Having protection status is no foolproof guarantee; much will depend on the fine print of what activities are permissible, the strength of enforcement and whether regular reviews are conducted. Under a fifth of protected areas in Southeast Asia undergo effectiveness evaluations, according to the World Database on Protected Areas.

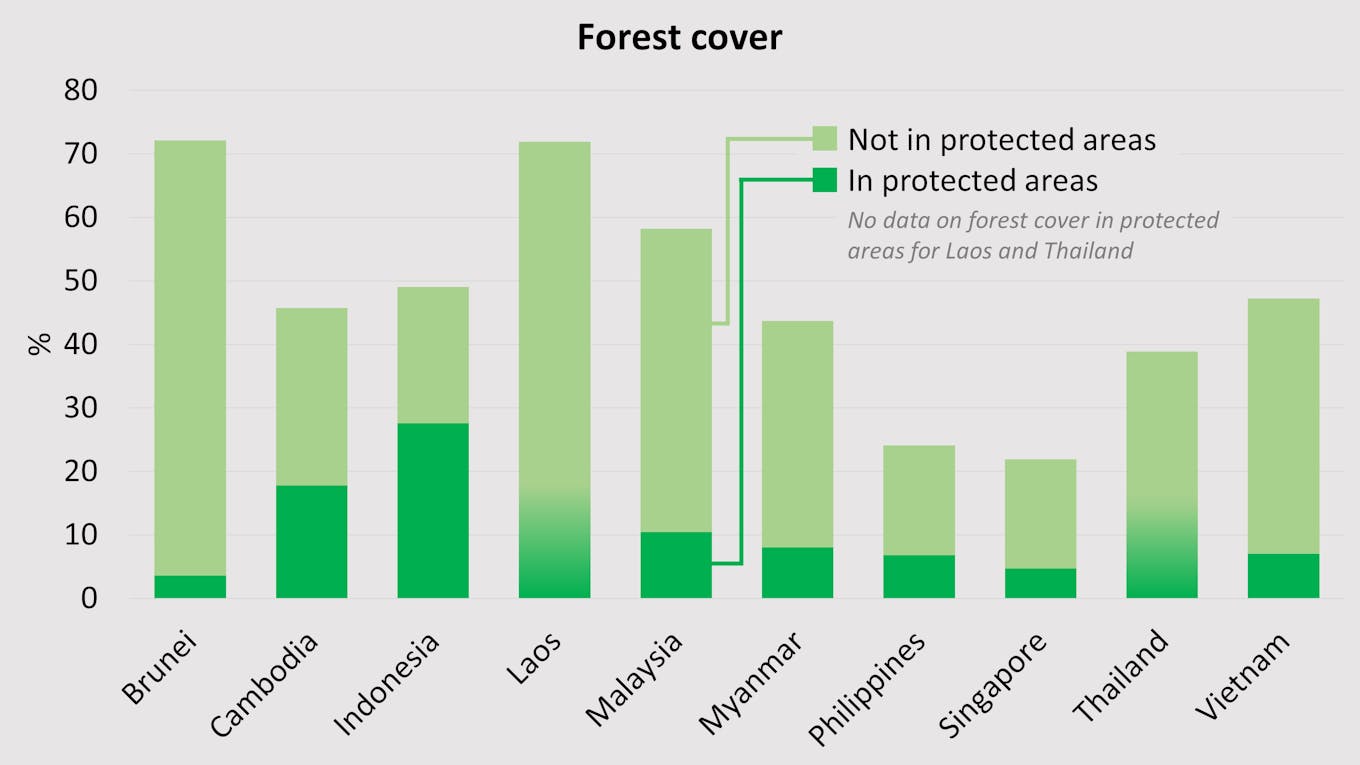

Data: Food and Agriculture Organization. Data from 2020 is shown.

Tropical forests dominate the natural landscape of Southeast Asia. Such biomes are home to a huge assortment of wildlife, and can store carbon dioxide to slow global warming. Some countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, have sizable forest cover, but many plots are not protected.

Agriculture is the main culprit for large-scale deforestation; jungle patches near settlements are also being eroded as more houses are built for the region’s burgeoning population. Deforestation has been blamed for worsening floods in Malaysia.

Countries such as Thailand and the Philippines could be “reaching their potential” in protecting more forests, since they presently have relatively low forest cover, said Surin. He said these countries could still conserve other ecosystems, like swamps, rivers and stone outcrops, which do host rare species.

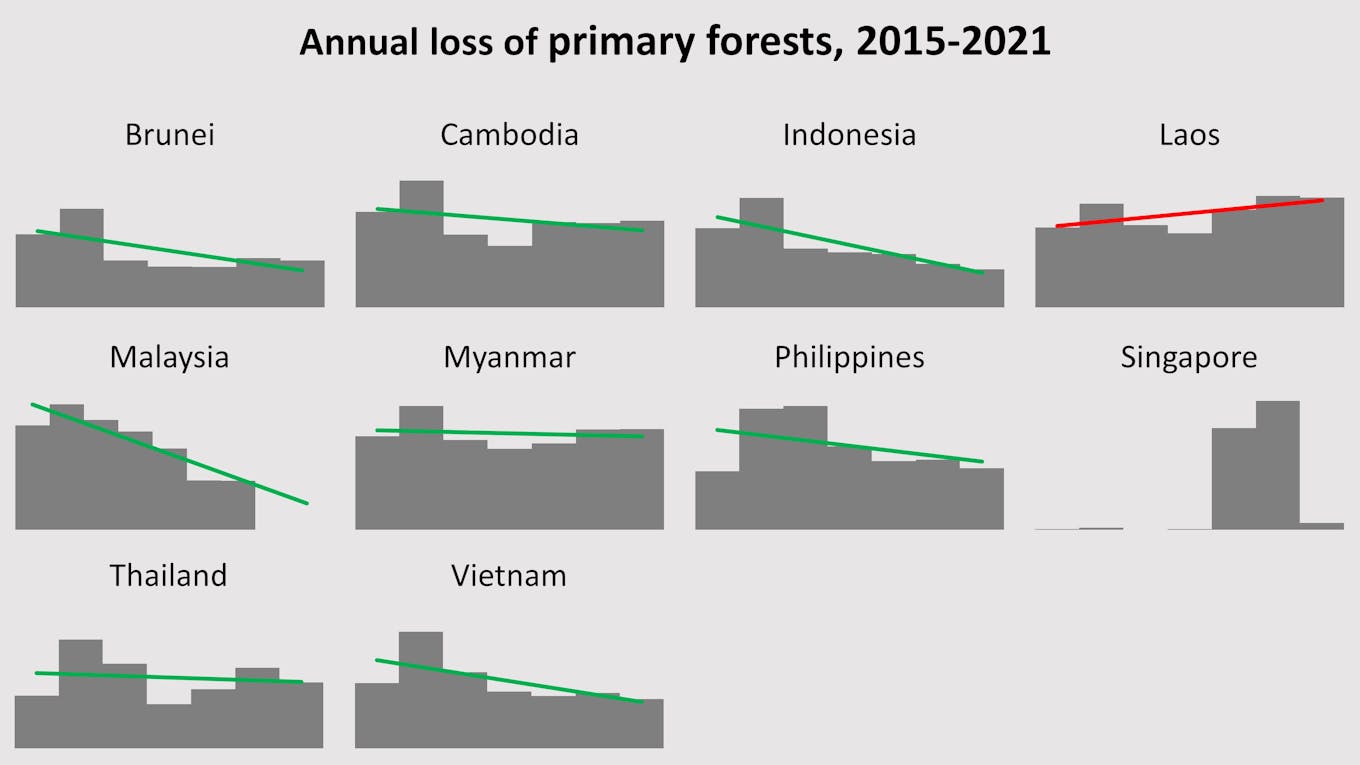

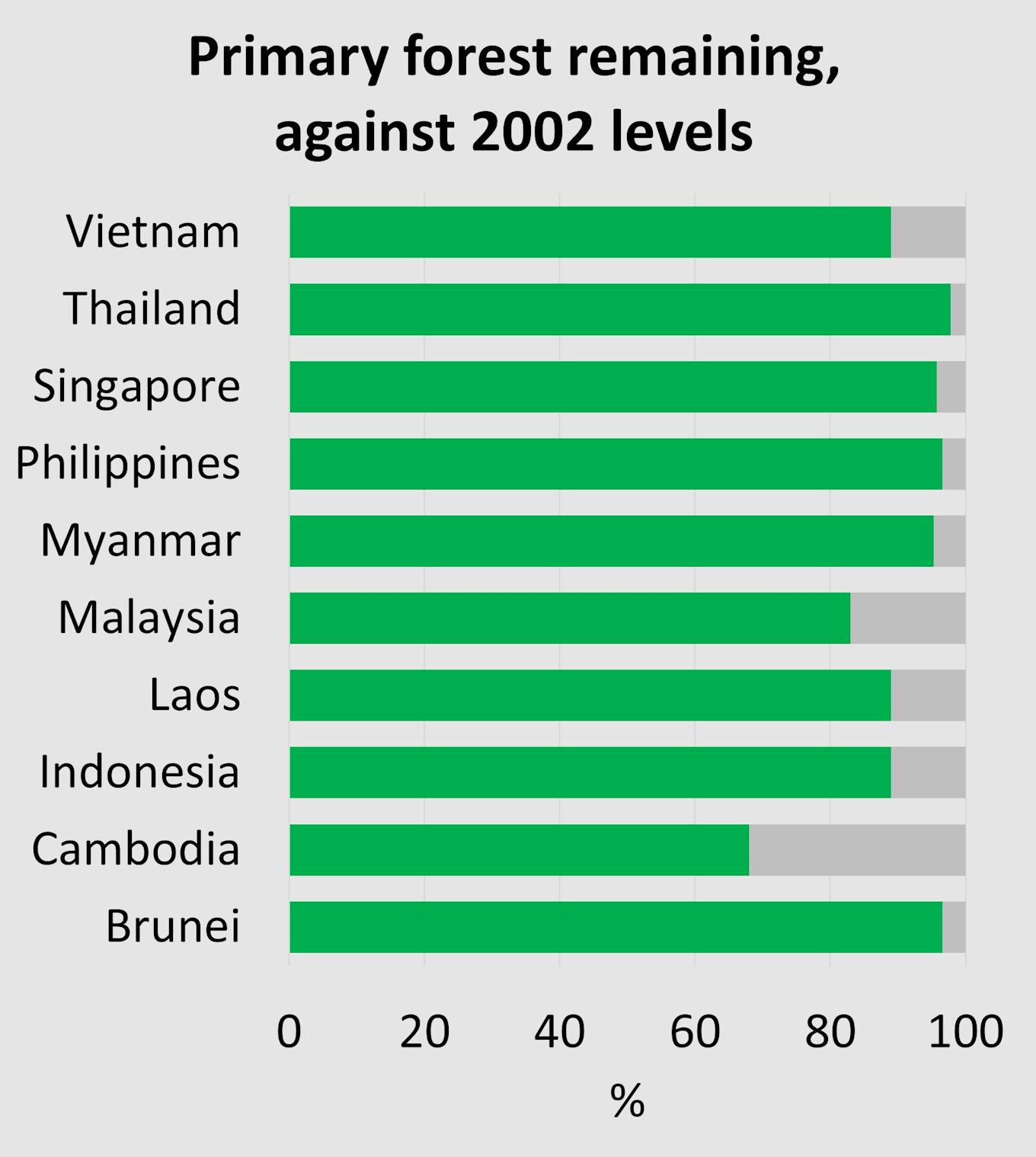

Data: Global Forest Watch.

Data: Global Forest Watch.

Meanwhile, Southeast Asia is still mowing down ‘primary’ forests, or pristine stands that have not been touched by humans for centuries or more.

The loss of such plots has slowed down in most countries, though the rate of primary forest loss since around 2019 is again creeping up in places like Cambodia and Myanmar.

Laos, meanwhile, is seeing a stubborn increase in primary forest loss since 2015.

Zeng Yiwen, a researcher at the National University of Singapore’s Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions, said land used to yield higher returns when converted into farms or mines, but the balance is tipping to favour conservation with the maturing of carbon markets, where corporates and governments pay to keep forests intact.

“Conservation must also involve and consider the needs of people living in or near the protected areas. Identifying how such economic and social factors affect our ability to safeguard forests and their species is key to conserving nature for future generations,” Zeng added.

The final text at COP15 repeatedly called for the participation of Indigenous and local communities in conservation initiatives.

New funding arrangements for developing countries agreed to at COP15, to the tune of US$30 billion a year by 2030, could also boost conservation efforts.

“Protecting biodiversity is not cheap. You need to make sure there are sufficient funds for people to carry out better patrolling and enforcement. People need to be paid,” Surin said, adding that greater technical knowledge and having political will are also needed.

Southeast Asia had not been ardent supporters of the latest 30 per cent conservation target in the lead-up to COP15. As recently as June this year, when some 100 countries globally have already voiced support for the target, Cambodia was the only Southeast Asia country to be part of that group.

An observer had said then that countries in the region could be wary of being told to set national 30 per cent conservation targets.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.