The average international conference attendee produces about half the carbon dioxide that the average person emits in an entire year just by attending a single event.

With Covid-19 pandemic travel restrictions loosening, the climate cost of events has come into focus as event organisers face growing pressure to limit their environmental footprint as physical event attendances rebound with a vengence.

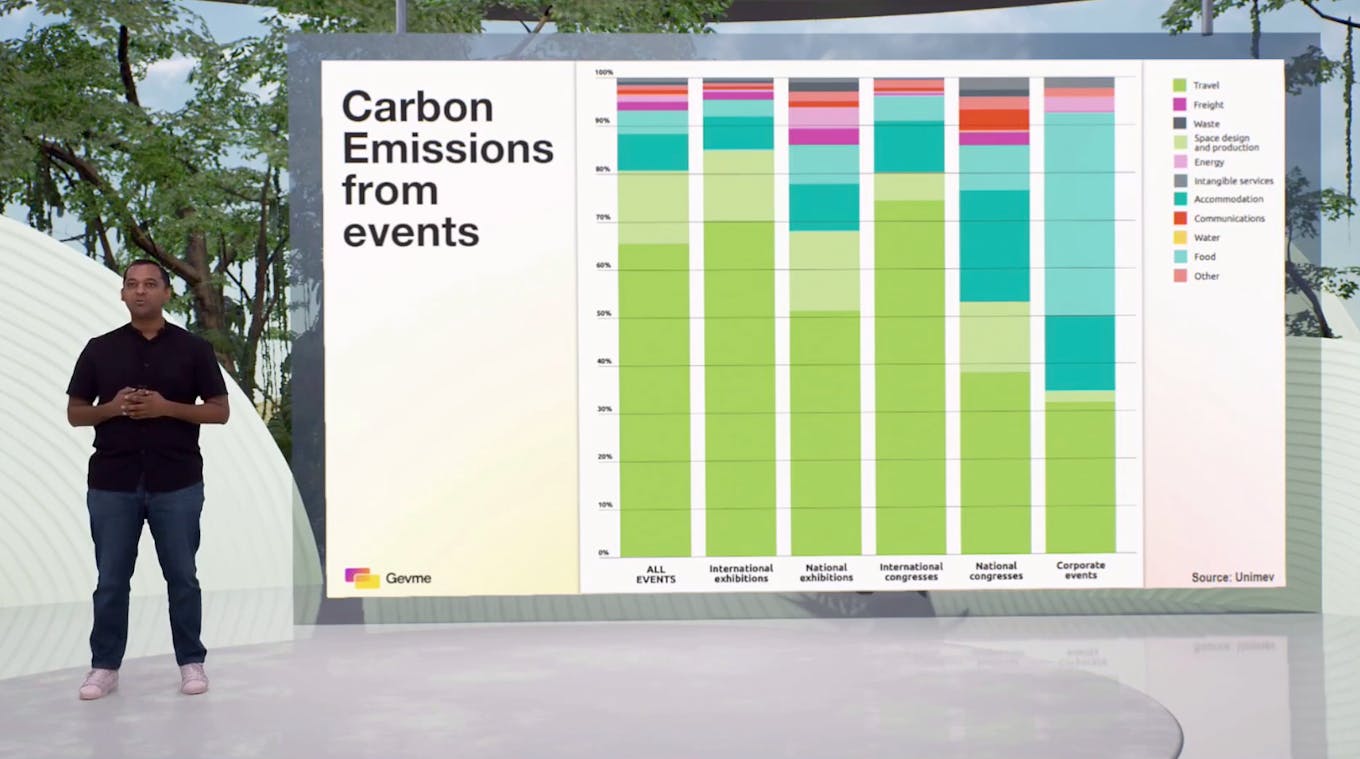

The biggest climate impact of an event comes from its Scope 3 emissions – air travel, which accounts for 70-90 per cent of the carbon footprint. This presents a dilemma for key business travel destinations such as Singapore, which simultaneously wants to be Asia’s leading sustainable meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions (MICE) hub while attracting more people from overseas to jet in for an event.

Singapore’s Grand Prix drew criticism for greenwashing in September for crowing about its efforts to reduce the operational environmental impact of the event by digitising tickets and using LED lights while ignoring the 70 per cent of emissions generated from transporting thousands of people and equipment to the city-state for a one-off, carbon-intensive event.

“

Single-use alternatives to plastic are not necessarily better. You need to ask yourself why you need single-use anything?

Stefanie Beitien, director, NorthSky Advisory

Singaporean officials expect the city-state’s events sector to have fully recovered by next year, with new events such as the Singapore Sail Grand Prix helping to jump-start the tourism sector as the country welcomes back visitors from a recently reopened China.

Veemal Gungadin, co-founder and CEO of digital events platform Gevme, presenting the relative climate impact of events while talking on his firm’s virtual platform. Travel is by far the biggest contributor to an event’s footprint, followed by production, accomodation and food. Image: Gevme

In Hong Kong, which lifted its mask-wearing mandate earlier this month, event attendances have almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels, with major events such as the Hong Kong Rugby Sevens returning after a three-year hiatus and a global finance conference in November an attempt to put the city back on the global financial map.

At the heart of the issue is that people have missed meeting in the flesh. Stefanie Beitien, director of sustainability consultancy NorthSky Advisory, who helps event organisers reduce their environmental impact, says while the on-stage portion of an event can be easily replicated virtually, the networking and coffee break tittle-tattle that business folk treasure cannot.

“We are social animals. We need social interaction. I feel very differently attending an event in-person,” she tells Eco-Business, adding that after Covid-induced Zoom-fatigue, she finds it increasingly difficult to concentrate at digital events.

“Networking is the most interesting bit of an event. There are some things that virtual events will never be able to fully substitute,” she says.

Events providers like Singapore-based firm Gevme are working on it. Its digital platform offers ways for attendees to interact in smaller groups, replicating the intimate coffee-break experience that people have craved in the Covid era, and proposes event organisers take an “omnichannel” approach to events, combining virtual and physical features to reduce their overall impact.

Digital technology also enables key stakeholders for sustainability events who wouldn’t otherwise be able to fly in, like smallholder farmers and textile factor workers, to have their say at important summits.

Gevme has its own target to half its own emissions and remove more carbon than it emits each year by 2030. It also aims to work with event organisers, building owners and visitors to limit the event industry’s impact by providing digital tools that encourage people attending events to make sustainable choices.

“When you consider the fact that more than 1.5 billion people attend business events every year, that shows how pressing a matter this is [for the climate],” says Gevme chief executive Veemal Gungadin.

Travelling light

So, how to reduce the travel impact of event-goers? The climate cost of transport does not just come from international jet-setting – although that is the biggest part, particularly long-haul flights from far-flung destinations.

“The passenger arriving to your event is your scope 3. Event organisers can’t not acknowledge how people get to and from an event – it’s their main contributor to the carbon footprint,” says Beitien.

Thankfully, hybrid panels are now an accepted part of the event experience. “People are familiar with the format. You don’t need to fly-in a speaker to give a speech for half an hour,” she says.

A lot can be done to mitigate travel carbon after a visitor has arrived, Beitien says. Like holding the event within walking distance of a partner hotel. Or arranging shuttle buses between the hotel and venue to avoid taxis or ride-hailers.

While carbon offsetting is always a last resort for emissions mitigation, international travellers can offset some of their footprint, which will – if reliable offset schemes are selected – allow money to flow back into carbon-sucking solutions, such as reforestation or mangrove-planting schemes.

Or event organisers can consider devising offsetting packages for international visitors, where partner airlines agree to offset passenger emissions for them.

Another big energy – and so climate – cost of events comes from cooling.

Anyone who’s attended an event in tropical Singapore – which expends about a third of its domestic energy consumption on cooling – will recall regretting to have brought a jacket. Too many event venues have, in their haste to keep guests comfortable, frozen them in the process – including the COP27 climate talks in Egypt, where attendees complained of sub-Arctic temperatures in conference halls.

“By setting the temperature at 24-25 degrees Celsius, you really can help to reduce the energy load,” says Beitien. Singaporean ministers don’t wear jackets, so why should event-goers?

The waste opportunity

Just as more people want to jet into a conference or exhibition, they expect greener events when they get there. Research from this year found that event organisers with a green platform enjoy a competitive advantage, while a study by Kearney found that people are more concerned about the environment than before the pandemic.

Waste is one area where event organisers have been expending a lot of energy to curb their environmental footprint – probably because waste is such a visible by-product of an event.

But efforts to curb waste won’t work unless it’s a coordinated effort between stakeholders.

“Recycling and waste efforts must be consistent throughout event management. It doesn’t help if you put out recycling bins, but you have a different agreement with the waste contractor,” says Beitien.

Coca-Cola-sponsored COP27 was criticised for selling plastic bottles of Coke on campus without the means to recycle the containers.

Beitien points out that replacing single-use plastic with another type of disposable container is a false solution.

“Single-use alternatives to plastic are not necessarily better. You need to ask yourself why you need single-use in the first place,” she says.

In Singapore, for example, where most waste is incinerated instead of recycled, plastic bottles are not the worst option. “If you switch to Tetrapak [a multi-layed packaging option made from plastic and paper] for water containers, that’s worse,” Beitien says.

The best way to reduce bottled water waste is water fountains, provided on site. This will become a more common solution as restrictions on single-use plastic come into play and water bottles become increasingly frowned upon by attendees.

But for water fountains to be effective at reducing waste, venues need to provide reuseable containers or encourage visitors to bring their own. Beitien suggests event organisers engage with visitors virtually, before they arrive and during the event, to remind them to bring their own reuseables.

“We weren’t allowed to provide glasses and jugs at an event [a conference on plastic reduction held by WWF, where Beitien used to work, in Singapore], so we asked event attendees to bring a bottle. Most people did,” she says.

Another way to curb waste is to cut down on gifting and giveaways. A study of hotels in Singapore by WWF found that more than 70 per cent of all amenity items like sewing kits and slippers are barely or never used. The figure is probably higher for events swag.

Beitien suggests that hotels offer amenities on-demand or in a reusable format and event organisers change how they thank their guest speakers. “A donation to a charity instead of a physical token of appreciation is the way to go,” says Beitien.

Measurement and responsibility

The biggest problem with managing an event’s environmental footprint is that it is difficult to measure. Where does an event begin and end? For instance, if food is cooked at a remote off-site venue, does that count towards the event’s emissions? How to track waste generated by a single event at a multi-event venue?

“You can’t take measures to reduce waste if you don’t know where the waste is coming from,” says Beitien, who recommends emissions calculators such as the Green Events Tool and SME Climate Hub to help businesses gauge their environmental footprint. ISO 20121 is a standard designed to help firms improve the sustainability of events while Singapore’s National Environment Agency offers a tool kit for the MICE industry to “reduce, reuse, recycle”.

On top of the measurement predicament is the question of who’s responsible for an event’s footprint. While the event organiser maybe ultimately responsible, they have to get stakeholders including the venue, hotels, stand builders, food caterers, printers, tech specialists and logistics providers in line, otherwise sustainability programmes won’t work.

“You need to engage with sub-suppliers or have clear guidelines in place for your sustainability efforts to pay off,” says Beitien.

Veemal Gungadin featured on the Eco-Business Podcast with Teymoor Nabili to talk about how a pandemic transformed the way sustainability events are conceived and organised.