A new report has found that more than three-quarters of the world’s planned plants have been scrapped since the Paris Agreement on climate change was signed in 2015, meaning 44 countries no longer have any future coal power plans. The remaining coal power plants in the pipeline are spread across 31 countries, half of which have only one planned for the future.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The climate groups behind the report published on Tuesday – E3G, Global Energy Monitor and Ember – said those countries now have the opportunity to subscribe to a “no new coal” commitment to help tackle global carbon emissions.

“The economics of coal have become increasingly uncompetitive in comparison to renewable energy, while the risk of stranded assets has increased. Governments can now act with confidence to commit to ‘no new coal’,” Chris Littlecott, report author and associate director at E3G said.

COP26, a United Nations climate conference in Glasgow in November, has been earmarked by COP president designate Alok Sharma as “the COP that consigns coal to history”. Sharma said that keeping global temperatures from rising by more than 1.5°C above pre-industrialised levels would be “extremely difficult” without a commitment from countries to phase out coal.

Coal is one of the biggest contributors to the carbon emissions responsible for the climate crisis, and the UN has said that the use of it must fall by 79 per cent compared with 2019 levels by the end of the decade if the world hopes to meet the Paris climate agreement targets.

Christine Shearer, the programme director at Global Energy Monitor, and co-author of the report, said that the COP26 climate talks are “an opportune time for the world’s leaders to come together and commit to a world with no new coal plants”.

Resistance to scrub-out coal remains. Ministers from more than 50 countries closed a two-day meeting in London in July without full agreement on the phasing out of coal.

A gathering of environment ministers from the G20 group of countries in Italy in the same month witnessed a stand-off with officials from China, India, Russia and Saudi Arabia blocking an agreement to end fossil-fuel subsidies and phase out the use of coal.

All eyes on Asia

Efforts to reduce a reliance on coal-fired power have stumbled in Asia, particularly as economies still reeling from the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have tried to jumpstart industrial activity.

Demand for electricity is also ballooning. Global electricity demand is forecast to grow by nearly 5 per cent in 2021 and by 4 per cent in 2022, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), with fossil-fuel-fired-power making up around 45 per cent this year, dropping slightly in 2022.

Japan and South Korea, countries in Asia that are in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of wealthy nations, have cancelled their remaining pipelines.

“Now we want to see them accelerating the retirement of their existing fleets in line with Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) and IEA emissions reductions pathways,” Leo Roberts a researcher at E3G and an author of the report said.

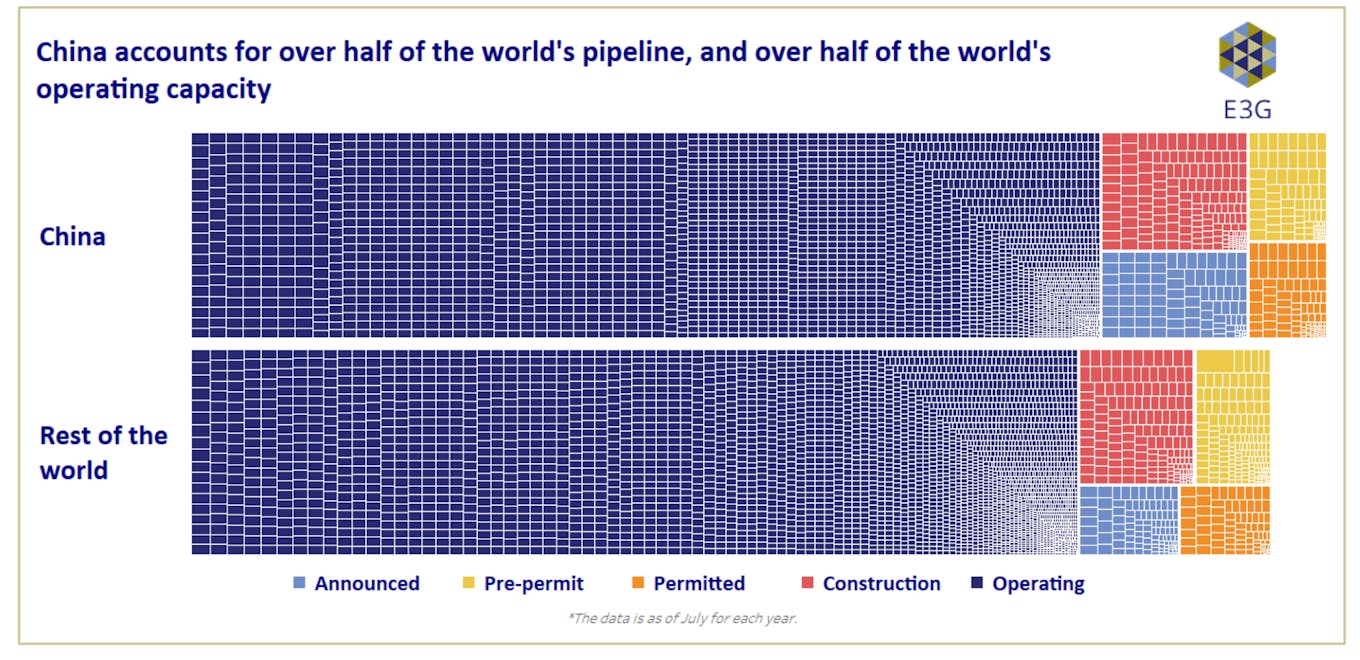

China still dominates the global coal landscape, accounting for 55 per cent of the world’s pre-construction pipeline, according to the report titled “No New Coal by 2021”.

China accounts for over half of the world’s pipeline, and over half of the world’s operating capacity. Image: E3G

As of July 2021, China and the countries with the next five biggest pre-construction pipelines — India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Turkey, and Bangladesh — account for over four-fifths of the world’s remaining pipeline. Action by these six countries could remove 82 per cent of the pre-construction pipeline, the report said.

“China has seen a massive collapse in the scale of its project pipeline, with a 74 per cent reduction since 2015,” Roberts told Eco-Business. “This equates to more than twice as much capacity being scrapped as actually going into operation, so even China is starting to move away from new coal.”

Nevertheless, the economic powerhouse is still propping up the overseas finance of new coal across the rest of Asia, and elsewhere with over 40 gigawatts (GW) of coal in 20 countries in the pre-construction pipeline.

While it is the “lender of last resort” for international coal projects, Roberts said, a policy change to shift China away from financing new coal would have a “dramatic positive impact on Asian and global aspirations to move away from coal.”

China has made some noises about ending overseas investment in coal. The deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China said recently that China would “strictly control new coal power investment overseas”. Nevertheless, China has not yet made a formal pledge to end support for coal abroad.

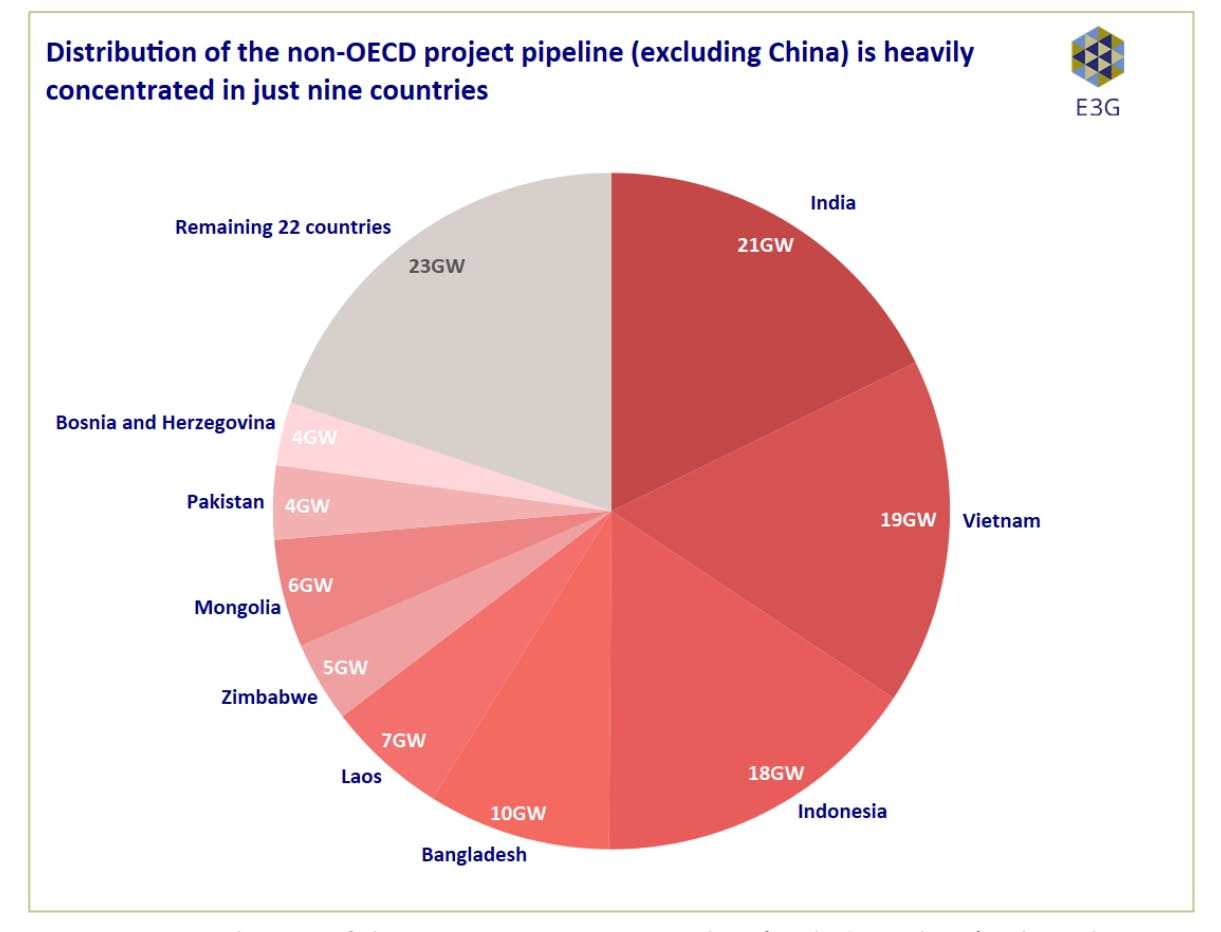

A group of countries outside the OECD is home to 39 per cent of the remaining global pre-construction pipeline, 80 per cent of which is located in just nine countries.

Distribution of the non-OECD project pipeline (excluding China) is heavily concentrated in just nine countries. Image: E3G.

Four of these governments—Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia and Vietnam—have already indicated some form of restriction on new coal construction. The remaining 20 per cent of the non-OECD pipeline is spread across small projects in 22 countries, many of which could readily commit to no new coal and pursue clean alternatives instead, the report said.

Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Philippines have all made clear policy statements or public commitments towards ‘no new coal’, while Vietnam and Indonesia have both started engaging on the idea, according to E3G analysis.

“Whether the early signals from these two countries will lead to a full moratoria is yet to be seen though, and there’s still a significant risk that they’ll add a lot of new coal to the global fleet in the next couple of years,” Roberts told Eco-Business.

Thailand, Cambodia and Laos now make up the bulk of the rest of the Southeast Asia pipeline, and have yet to openly explore cancelling new coal plans in spite of huge potential for renewable energy and transboundary power-pooling.

According to Roberts: “those countries still considering new power plants should urgently recognise the inevitability of the global shift away from coal, and avoid the costly mistake of building new projects.”