More than 100 countries, including the United States and those in the European Union have signed up to a new commitment to reduce emissions of methane, a more powerful, but shorter-lived, greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The Global Methane Pledge, which aims to reduce emissions of the gas by 30 per cent by 2030, was launched at the United Nations climate conference—COP26—in Glasgow. Countries representing 70 per cent of the global economy and nearly half of anthropogenic methane emissions have now signed on to the pledge, although a handful of the world’s major emitters including China, Russia and India, have not joined the pact.

The number of countries signing onto the pledge has grown from just six when the initiative was initially launched in September. It is one of the success stories of the Glasgow talks, that have been otherwise underwhelming.

Although carbon dioxide is the major focus of climate talks, methane has a higher heat-trapping potential. Burping cattle, coal mines, forest fires, rice paddies, slash-and-burn agriculture, landfill, wastewater-treatment plants, vehicles, and natural ecosystems such as swamps, rivers and lakes all discharge the potent greenhouse gas.

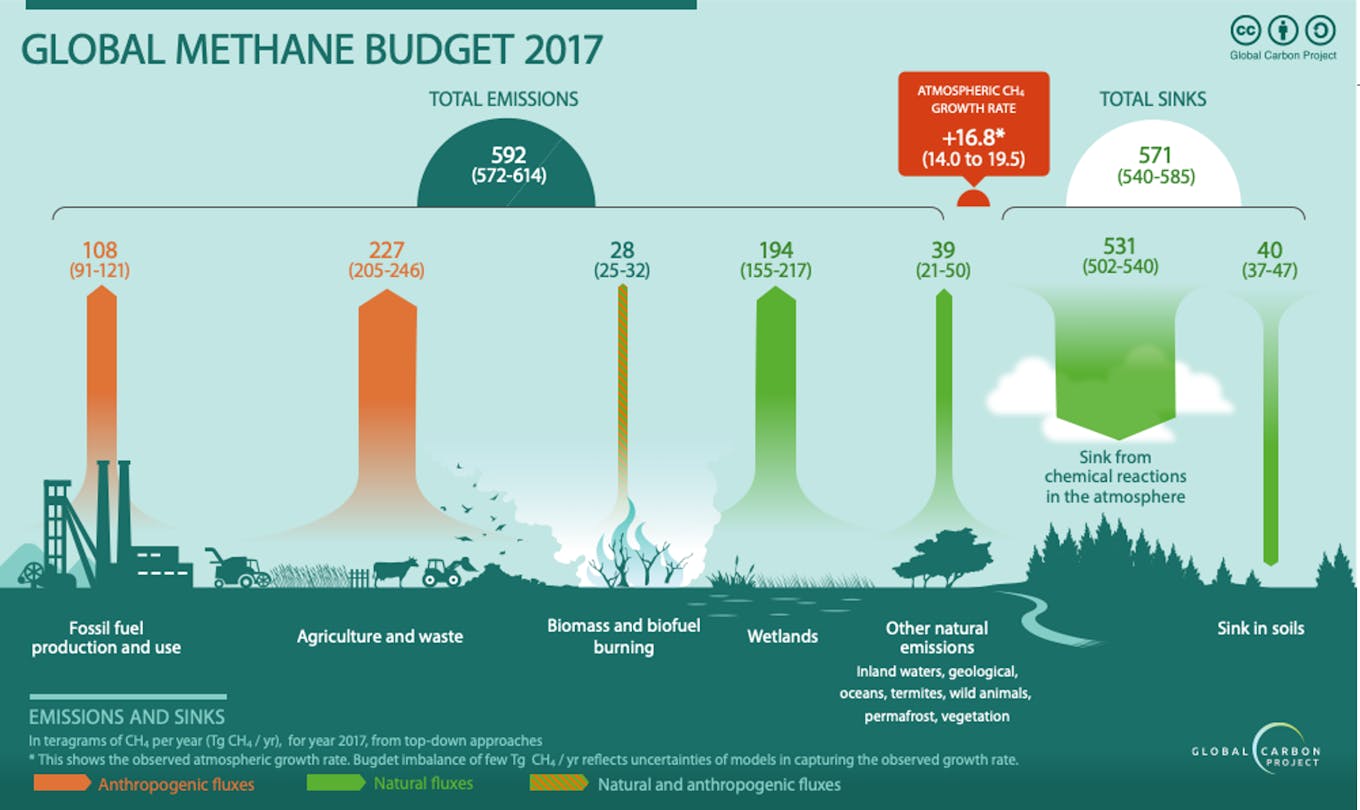

Anthropogenic sources are responsible for all or most of the recent rapid rise in global CH4 concentrations, equally from agriculture and fossil fuels sources, according to Global Carbon Project. Source: Jackson et al. 2020, ERL (Fig. 1).

Methane has accounted for roughly 30 per cent of global warming since pre-industrial times and more than 300 million tonnes are emitted every year because of human activity, and that rate is growing.

“Cutting methane is the strongest lever we have to slow climate change over the next 25 years and complements necessary efforts to reduce carbon dioxide,” said Inger Anderson, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

A UN scientific report released in August said “strong, rapid and sustained reductions” in methane emissions, in addition to slashing CO2 emissions, could have a fast impact on the climate.

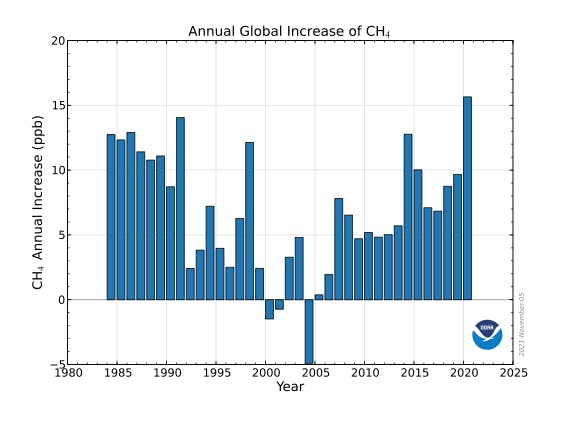

Annual increases in atmospheric CH4vbased on globally averaged marine surface data. [Click to enlarge]. Image: NOAA

The Climate and Clean Air Coalition, a group of governments and environmental lobbyists, reckon that a 45 per cent reduction in human-caused methane emissions would avoid nearly 0.3°C of global warming by 2045.

Because methane is a key ingredient in the formation of smog, a dangerous air pollutant, a 45 per cent reduction would also prevent 260,000 premature deaths, 775,000 asthma-related hospital visits, 73 billion hours of lost labour from extreme heat, and 25 million tonnes of crop losses annually, according to the CCAC’s Global Methane Assessment, published in May.

The UN and the EU launched a global watchdog on 31 October to monitor governments’ pledged reductions of methane that have the potential to make a rapid contribution to limiting temperature rises.

Seaweed, catching burps and plugging leaks

Experts believe that tackling methane emissions is a relatively straight forward and cost effective way to tackle global warming. Roughly 60 per cent of available targeted measures have low mitigation costs, with over half of those with the potential to save money, according to CCAC analysis.

Measuring the colourless, odourless gas is complex but land-based and aerial studies show that leaky well and pipelines are one large culprit of methane emissions. US President Joe Biden intends to restore policies that will limit the methane coming from the country’s roughly one million existing oil and gas rigs.

The new International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO) aims to provide credible data to track government progress on meeting methane reduction pledges and to promote best practice. MethaneSat, a non-profit, aims to launch an ecosystem of methane-detecting satellites next year that will scan the Earth’s surface every few days to report point-sources.

Closing down coal mines would help significantly. The world’s coal mines spout roughly 40 million tonnes of methane, according to the International Energy Agency, and account for about 9 per cent of human-related methane emissions. The leakages could be having as much as an impact on global warming as burning the coal they produce, researchers from Global Energy Monitor, a San-Francisco-based non-profit said in a study in March.

“Methane emissions from coal have received much less attention from researchers and governments than methane emissions from oil and gas,” researchers said in the report. “The gap in attention has resulted in a deficit in implementation of measures to mitigate what by all estimates is one of the most significant sources of greenhouse gases.”

While coal is on its way out, the overwhleming majority of new coal-fired generation is developing in Asia. Coal capacity has doubled in Southeast Asia since 2010.

There has been significant interest at COP26 in a potential technology fix to achieve the rapid removal of methane from the atmosphere. Scaling this technology from the lab to the atmosphere remains a hurdle. Countries will also have to agree to pay for such programmes. Scientists are urging for the private sector and governments to financially commit to the removal of methane on the same scale as carbon capture technology.

Made from a bendable, rubber-like plastic, the Zelp mask attaches to a standard bovine halter and rests just above the cow’s nostrils. A set of fans powered by solar-charged batteries sucks up the burps and traps them in a chamber with a methane-absorbing filter. Once the filter is saturated, a chemical reaction turns the methane (CH₄) into carbon dioxide. Image: Zelp/Disclosure

Other attempts are a little more creative. A UK-based supermarket chain has started to trial feeding cows seaweed in an attempt to reduce “burps and flatulence” and cut methane emissions. Some 95 per cent of methane released by cattle comes out as burps and through the nose. Academic studies have shown using seaweed as a dietary supplement can cut methane emissions by more than 80 per cent.

Agriculture giant, Cargill, meanwhile is selling methane-absorbing wearable devices for cows, backing an experimental technology to help cut greenhouse gas emissions. The mask-like accessory was developed by British startup Zelp Ltd., which claims it can reduce methane emissions by more than half. Cargill said in June that it expects to start offering the devices to European dairy farmers in 2022.

However, much like carbon emissions, cracking down on methane will take a global effort. Neither China, the world’s largest emitter of methane because of its rice paddies, nor Russia, not just the second biggest natural gas producer but also one with the leakiest infrastructure, have signed up to the 30 per cent reduction by 2030 goal. India has pushed back as well because of the potential impact on rural livelihoods that rely on livestock farming.

The pledge is a weaker one as a result. “The real work begins now,” according to energy expert Maria Pastukhova at E3G, a think tank. “Before COP27, the pledge must get the top three emitters — China, Russia and India — on board, supported by a transparent governance and monitoring mechanism.”