Was there ramped-up ambition this year, or were firms mostly making empty vows about how sustainability is in their DNA? It is hard to tell with the green-bashing, bleaching and hushing in the business world, which could do with a little more corporate vulnerability and less competence greenwashing. The industry also grappled with climate quitting, biodiversity credits and Scope 4 accounting. Meanwhile, deinfluencing is trending, while deadnaming was punished in court. Hope you are keeping solastalgia at bay amid the global boiling and polycrisis.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Good job, if you managed to read that paragraph in a single breath. How many sustainability catchphrases did you pick out? Eco-Business unpacks the terms we hear recurrently in a turbulent year that strained markets and societies.

Ambition

It is certainly not a new buzzword, but the term was used endlessly by officials at the recent COP28 climate summit, especially when they were talking about action to phase out fossil fuels.

Simon Stiell, who heads climate change work at the United Nations, called the conference an “ambition exercise” before it started. A few days in, he said there were “low, middle, and high ambition options” on many issues. As talks entered crunch time, he urged policymakers to strive for the “highest ambition” outcomes, a call echoed by summit president Sultan Al Jaber of the United Arab Emirates.

In the end, as countries agreed to “transition away” from fossil fuels, Stiell said the agreement is a floor, not a ceiling, and that the world “must ramp up ambition”. Zhao Yingmin, a Chinese official, said climate action needs to feature “both ambition and pragmatism”. Anusha Mata, analyst at UK-based think-tank E3G, said the final text “does not fully live up to ardent calls for higher ambition”, especially from climate vulnerable countries.

Transition (and ‘Transition-washing’)

Beyond COP28’s fossil “transition” compromise, this year also saw big names join efforts to transition Asia away from coal. US$150 trillion climate finance group GFANZ joined the Monetary Authority of Singapore to craft policies on the early closure of coal plants. Singapore, along with private sector partners and the Asian Development Bank, also announced a plan to use “transition” carbon credits for retiring coal plants in the Philippines.

Meanwhile, Indonesia and Vietnam released plans on how they will use a combined US$35.5 billion of “Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP)” investments from wealthy countries and GFANZ to shift towards clean energy.

The transition movement follows from a wave of coal divestitures in past years, which sceptics say just puts pollutive assets in the hands of shadier private financiers.

Some observers, meanwhile, warn of risks in mismanaged transitions, in living costs and loss of livelihoods for local communities. Vietnam’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) plan is taking place while climate activists are getting arrested, they point out. Meanwhile, fossil fuel businesses may not move as fast without the threat of divestment, and financiers themselves could exploit loopholes that regulators are starting to call “transition-washing”.

Corporate vulnerability

An antidote to sustainability clichés, perhaps? Public relations experts are now calling for more humility in how brands talk about their sustainability journey. Showing “corporate vulnerability” by being honest about mistakes and sharing reflections are untested opportunities in avoiding reputational risks and building trust and camaraderie, they say.

Earlier this year, Stephan Loerke, chief executive of the World Federation of Advertisers, called on colleagues to be “open about your challenges” in sustainability publicity. “Monitoring and publishing data that shows how you are progressing on the journey is critical to credibility”, he said.

A report by brand manager Vero for sustainability communication in Southeast Asia also exhorted the merits of “candour to the point of vulnerability”, through constantly checking against common greenwashing mistakes, such as a lack of evidence, being vague and omitting negatives.

“Too much of corporate communication focuses on crafting an idealised image that disguises the imperfect realities of doing business in the modern world. We hope to push back against that tendency, at least in this realm where lack of transparency poses a quite literal threat to the world we all share,” it said.

Competence greenwashing

First emerging in 2020 and fully in the spotlight this year, the term refers to jobseekers and corporates embellishing sustainability credentials to get a better job or land lucrative green business contracts.

The rise of this new variant of greenwashing coincides with market demand for sustainability professionals exceeding supply. It has been flagged as an issue for Singapore as the city-state tries to position itself as Asia’s sustainable finance hub. In the wider job market, there could also be a push towards generalist sustainability roles, which could be overshadowing the need for technical specialists in areas such as biodiversity.

Competence greenwashing could erode trust and cause sustainability initiatives to underdeliver.

“The industry-wide lack of material environment, social and governance (ESG) expertise and granular knowledge around the complexity of sustainability issues, especially in the ‘E’ category, should be a red flag in terms of the scientific robustness of any ESG review,” wrote Prof Kim Schumacher, who coined the term.

Green-bashing, bleaching, hushing

Greenwashing has been around long enough to spawn countercultures. Just this month, a report by the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) wrote that “in addition to greenwashing, other malpractices such as green-hushing and green-bleaching are becoming prominent”.

Green-bleaching refers to when financiers underplay the sustainability credentials of their funds to avoid regulatory scrutiny, while greenhushing is when companies keep mum on their sustainability initiatives lest watchdogs find loopholes in them. IOSCO said some regulators globally think such practices constitute unclear communications.

In another sign of how prevalent the practices are, late last year, consultancy South Pole found that a quarter of 1,200 firms surveyed are keeping quiet on their science-based net-zero emissions targets.

The phenomena could be a response to green-bashing, where vigilantes call out and sometimes organise boycotts against firms for sustainability wrongdoings.

Carbon markets would particularly feel they are victims of green-bashing, starting with UK newspaper Guardian’s indictment of credit certifier Verra, and the string of investigations into questionable carbon projects that followed. South Pole itself landed in hot water over its massive Zimbabwe forest project alleged to have been mismanaged and sold too many credits.

Observers have conceded there are black sheep but said many good projects also exist. The carbon market is still in a slump as buyers remain wary of reputation risks.

‘Sustainability is in our DNA’ (and similar)

We covered this in one of our top-read opinion pieces this year. Corporates are lining up to make such proclamations in their brand communications and sustainability reports, perhaps reflecting a “safety in sameness” as consumers increasingly demand for green buys, according to one observer.

Whether these proclamations are genuine will require a deep-dive into what businesses are actually doing in support of their statements. But the ubiquity of claims such as “sustainability is at the heart of everything we do” or “sustainability is in our core” is undeniable: each of these terms return tens to hundreds of thousands of results in Google searches.

Global boiling

United Nations secretary general Antonio Guterres is known for impassioned quips when speaking about climate change, and his line for 2023 is particularly fiery. “The era of global warming has ended. The era of global boiling has arrived,” Guterres said, as scientists announced that July this year is the hottest month on record.

Scientists also recently confirmed that 2023 is the hottest year on record, with January to November being on average 1.46°C warmer than pre-industrial times. Researchers have previously said 1.5°C is a safety limit for temperature rise, against more severe extreme weather events.

United Nations secretary-general Antonio Guterres addressing world leaders at the COP28 climate conference. Image: Flickr/ UNclimatechange.

Scope 4

As if Scope 3 isn’t complex enough for carbon accountants to grapple with, a new category of emissions is now making its rounds, and gaining big-name supporters such as Japan’s tech giant Panasonic and America’s Pacific Gas & Electric Company.

Scope 4 essentially refers to emissions avoided through the use of products and services that are energy efficient. For instance, a gas power plant may make the argument that its use can help to avoid even more emissions had a more pollutive coal plant be built in its absence.

Sounds familiar? While such a concept is nascent in carbon accounting, it is already mainstream in carbon offsetting. Forest managers use avoided emissions to calculate the benefits of keeping trees standing in areas of high deforestation risk (and in the process attracting the ire of critics).

So observers are similarly at loggerheads with the new Scope 4 concept. Some say it reflects the true value companies bring to decarbonisation, while others claim the idea moot because it does not deal with real greenhouse gases being emitted.

As a reminder: Scope 1 refers to emissions from a company’s own operations, Scope 2 from the company’s electricity used, and Scope 3 from the company’s supply chain and customers.

Biodiversity credits

Last year, plastic credits got its moment in the sun amid talks to curb plastic waste globally. This year, the limelight has turned to biodiversity credits, as countries globally commit to protecting 30 per cent of the world’s nature without quite figuring out how to fund the effort.

The World Economic Forum believes corporate funding of conservation work, to “offset” losses from construction projects elsewhere, could reach US$2 billion in 2030 and US$69 billion by 2050.

In many ways, both the promises and risks of commodifying biodiversity protection are evident from what has been happening in the carbon market. A well-functioning business model creates a sustainable flow of money to cash-strapped conservationists. But without watertight rules, cowboy developers will game the system and sideline vulnerable local communities. It is also scientifically hard to determine if biodiversity loss in one area can truly be exchanged one-for-one with protection in another.

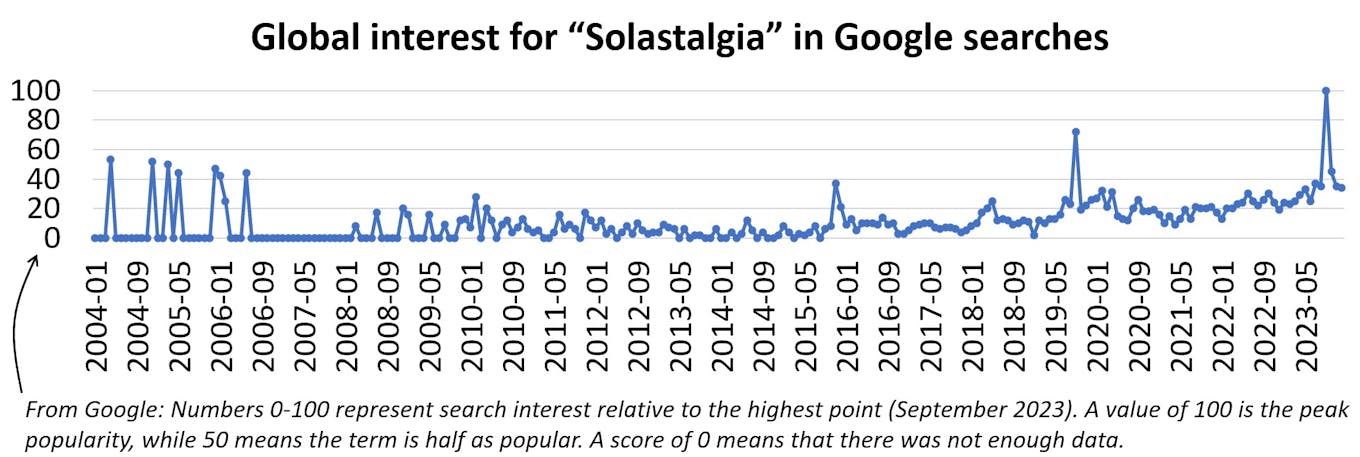

Solastalgia

Ever feel down thinking about the state of the environment today? Now you can place a name to that apprehension. Solastalgia could be triggered by extreme climate events – wildfires, storms, droughts – or the realisation that the creep of global warming has made one’s environment unrecognisable. It falls under the more general eco-anxiety phenomenon, which also counts emotions such as guilt and frustration.

The term had been coined back in 2005 by an Australian researcher, Professor Glenn Albrecht, but has gained prominence in recent years as climate change becomes more noticeable worldwide.

Source: Google; Image: Eco-Business

This psychologist suggests joining community environmental activities, practising eco-art therapy and using virtual reality to experience one’s ideal surroundings as antidotes. Albrecht himself came up with another term, “soliphilia”, where people feel love, responsibility and a desire to help heal nature around them.

Climate quitting

Amid grievance that their employers are not moving fast enough to address climate change, some workers are calling it quits and switching to “greener” jobs. Research run by former Unilever chief executive Paul Polman this year found that over 40 per cent of 4,000 United States and United Kingdom workers would think of quitting if their employers’ values did not align with theirs. Meanwhile, consultancy KPMG said a third of 18-24-year-old UK jobseekers have turned down offers from poor ESG performers.

Some link the trend to the larger conscious-quitting movement, where employees are said to be rethinking what matters in their careers after the pandemic, which killed many and exposed the fragility of contemporary capital systems.

“That might not be great news for companies that take a lax approach to articulating ESG principles. But there is also an opportunity for these businesses, since an organisation’s climate policies can also positively affect employee retention,” KPMG said of the climate quitting trend.

Deadnaming

Employer alert: addressing people by their birth names before they changed gender identity could land you in hot soup, as the transport department of a UK borough found out this year. The office was made to pay an employee over US$31,500 in a civil suit for repeatedly using her outdated name – deadname – for at least two years.

Awareness about deadnaming increased earlier this year as several states in the US considered legislation that could compel schools to deadname trans students or report them to their parents.

Progress elsewhere is mixed. Messaging platform Discord said this month it could ban users if they misgendered and deadnamed others. Meanwhile, Twitter (now X), which enacted similar policies in 2018, rolled them back in April. Advocates say deadnaming inflicts trauma on victims and invalidates their identity.

Deinfluencing

Do you rely on influencers to help you pick your next shirt or shoe purchase? You may soon come across personalities helping you narrow your choices instead – sometimes on sustainability grounds.

A growing caucus of online gurus are here to tell you that overconsumption and fast fashion is out of vogue. Here’s someone telling you not to overhaul your wardrobe for no good reason. Another account counsels against Apple’s Airpods, or Dyson’s premium hair stylers.

The tag #deinfluencing on Tiktok was viewed 100 million times at the start of the year. The figure has since grown to 1.1 billion.

Some deinfluencers are also calling out big brands for overcharging on their products, while recommending budget face creams and hair gels that work just as well – useful guides amid the economic headwinds.

Polycrisis

The World Economic Forum warned at the start of the year that we are in the middle of a “polycrisis” – the pandemic’s long tail is still tripping Asian economies, the war in Ukraine seems to have no end, the cost of living is sky-high, all while the climate continues to heat up dangerously. Italian climate think-tank CMCC Foundation opined that we need to be prepared for a polycrisis “era”.

Now, add Israel’s war in Gaza to the list of troubles to deal with, before everyone can focus again on addressing global warming.

The world has in the past faced many problems at the same time. The term polycrisis was used as early as the 1970s, when the United States was defeated in the Vietnam war, and experts were first warning about the limits to growth.

We have, on balance, managed to get through those episodes. Many people emerged better off. Do we now have what it takes to tide through another rough wave? Pray tell, 2024.

Did we miss any buzzwords or green terms? Let us know by sending your comments to news@eco-business.com. This story is part of our Year in Review series.