Shahar “Shaq” Koyok is descended from the Temuan people, one of the largest tribes of Malaysia’s Indigenous peoples, or Orang Asli (which means “first people” in Malay).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

An artist and Indigenous rights activist, Shaq almost exclusively paints members of his tribe, to earn a living and to tell the story of their struggles.

Indigenous peoples in Malaysia face a range of threats to their traditional way of life, not least the loss of the forests they call home.

Last year, Malaysia lost 123,000 hectares of natural forest. This is equivalent to 87 million tonnes of carbon emissions – and thousands of Indigenous people’s source food, energy and way of life.

Shaq Koyok, 37 year-old artist and Indigenous rights activist is descended from the Temuan people, one of 19 Orang Asli tribes in Peninsula Malaysia. Image: Shaq Koyok

Shaq was recently at the heart of a campaign to save Kuala Langat forest reserve, a rare patch of ancient peat forest not far from Malaysia’s capital, Kuala Lumpur, where Temuans have lived since the 1800s.

Last May, a big chunk of the nature reserve was quietly degazetted to make way for property developers, sparking a public outcry. Shaq was part of a movement that stopped the bulldozing of the 8,000-year-old forests.

The reserve has been a lifeline for the Temuans during the Covid-19 pandemic, providing food and water for the many who had lost their jobs. “For us, the jungle is our shopping mall, pharmacy and grocery store,” said Shaq.

The 37 year-old artist grew up in a Temuan village in Banting, about 20 kilometres from the reserve. From modest beginnings in a one-room house without running water or electricity, Shaq became one of the first Orang Asli to attend the Universiti Teknologi Mara in Shah Alam, where he studied fine arts.

“

Our story is not told in history books. The campaign to save Kuala Langat forest helped to tell our story, and people who didn’t know our story rallied to help us.

Shaq Koyok, Indigenous artist and activist

Through his paintings, Shaq gives a voice to a people often ignored. Though the role of Indigenous peoples in protecting wildernesses has started to be recognised – a 2020 United Nations study finds that Indigenous communities keep intact nature worth $33 trillion to the global economy – their voice is rarely represented at the big events that decide global environmental policy, Shaq says.

The salvation of Kuala Langat forest reserve was not only a rare example of public opposition beating the bulldozers. It was also one of the few incidences of Indigenous rights being heard in Malaysia, says Shaq. “For generations, Indigenous people have had to fight for our forests on our own. But we are not alone anymore. The campaign brought us together as a community,” he said.

In this interview, Shaq talks about the perils of defending Indigenous rights in Malaysia, his feelings about the recent death of the Queen, carbon credits, and finding a balance between modern and traditional life.

What effect did the victory in protecting the Kuala Langat nature reserve have for your community?

It was really empowering. For me, it showed that people power really works. And it showed how a community can work together. For generations, Indigenous people have had to fight for our forests on our own. But we are not alone anymore. The authorities tried to fight us from many angles, but the campaign brought us together as a community. A victory like this is rare in Malaysia.

For us, the forest isn’t just our livelihood. It is our way of life, our identity, our culture. But this narrative is not taught in school. Our story is not told in history books. The campaign to save Kuala Langat forest helped to tell our story, and people who didn’t know our story rallied to help us. More importantly, they wanted to learn about our existence and way of life.

Shaq Koyok (left) with community members protesting against the degazettement of Kuala Langsat nature reserve. Image: Shaq Koyok

A lot of campaigns to save forests around Southeast Asia are not successful. How come your campaign worked?

It helped that the forest was close to Kuala Lumpur, where many non-government organisations are based. It was easy for me to take other activists, artists and friends from the city to the forest to show them what was at stake, and what we could lose. They made a connection with the forest. Then our fight became their fight. Too many forests have been lost because Indigenous peoples have had to fight alone.

A poster protesting against the degazettement of Kuala Langat forest reserve. Image: Shaq Koyok

Do you feel like Indigenous people are getting fairly recognised for their role as forest guardians?

More so now. The Covid-19 pandemic was caused by the plundering of nature, which allowed diseases to develop. A silver lining of the pandemic has been growing recognition of humanity’s impact on the environment, and I think more people now recognise that Indigenous people are key to preventing deforestation. This recognition could help us get more support in our campaigns to protect customary forests.

Where is the focus of your campaigning now?

I am campaigning to save the forest at Bukit Cerakah. More than 400 hectares of the forest were degazetted by the government of Selangor in May for property development. There is an Indigenous village there. My uncle is from there. He lived in Kampung Air Kuning, next to the forest. Two of my brothers work in this forest. Construction work has already started, and the top of the hill has been deforested. Campaigners are trying to stop it. The government is now claiming that the forest was degazetted long ago.

Bukit Cherakah Forest Reserve. A hilly section of the reserve has already been deforested. Over the years, Malayan Tapirs have been killed on the road that runs through the reserve. Image: Shah Alam Forest Society

Bukit Cerakah forest reserve is a special place. It is home to endangered animals such as the Malayan tapir, hornbills and the Sunda pangolin. There are also more than 450 species of plants in the reserve, many of which are very significant to the community. Recently, the community who lives there saw a Malayan tapir in their backyard. Tapirs are shy animals with excellent hearing. It is very rare to see them. It felt like this one was asking for help.

The problem is that this is a land rights issue. The forest is not gazetted as an Indigenous reserve. It is a forest reserve. So the people who live there are not protected. We want to fight to save the community as well as the biodiversity that exists in the forest.

“

I don’t think carbon markets will help [fight climate change] – they will make it worse…The future is going to be very bleak if we rely on carbon offsets and net-zero targets.

How realistic is winning this campaign?

Stopping the destruction of the Kuala Langat forest reserve is a benchmark. We are hopeful we can repeat the feat. We have to. We cannot let the government use excuses that the land was degazetted long ago. We are dealing with the impacts of climate change every day now. We need our forests to survive. Shah Alam [the city in the region of the Bukit Cerakah Forest Reserve] was hit by a major flood in December. Without the forest, flooding will be a big problem for people living in the area. We need to get that message through to people.

Southeast Asia is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be an environmental defender. Do you feel threatened as an activist in Malaysia at the moment?

It is indeed worrying that Indigenous activists are under threat for trying to protect the environment, which we all share.

“Lupak Nyap” (“never forget” in Temuan language) acryllic on canvass. An Indigenous activist holding a sapling. Image: Shaq Koyok

Recently, I was threatened with legal action by the Selangor authorities for asking a question about the degazettement of part of Bukit Cerakah Forest Reserve. I asked the Menteri Besar (chief minister) how he could let the degazettement happen; he is supposedly to be in service of the public, but he is doing nothing to help the public – so he might as well resign.

During the campaign to save Kuala Langat, I was told that someone in the village had become a spy for the authorities, and would alert them every time I went to the forest. So now, I don’t tell anyone about my movements and am careful with how I use social media.

You have travelled a lot recently and attended a leadership programme for NGOs and Indigenous artists and activists in the United Kingdom. What did you learn?

We had an agreement not to disclose details from our discussion. It involves politics and human rights – both very sensitive topics. It concerns vulnerable people who are being watched by the authorities in their countries. It was empowering knowing that we are fighting the same fight.

One idea I found intriguing is the idea of guerilla planting [cultivating land without the legal right to do so]. The UK has a huge issue with biodiversity loss to agriculture. Farmers are trying to squeeze more profit out of the land, using the excuse of the food crisis to encroach further into wild areas. But guerilla planters are quietly, secretly restoring patches of forest by planting native saplings.

The main rule for guerilla planting is to not take pictures or put anything on social media. If you want to get a kick out of seeing the forest regrow, you have to go back and see it for yourself – just smile at it and let it grow.

Indigenous activists face many threats, and often it does no good to show off what you are doing on social media, because it can backfire.

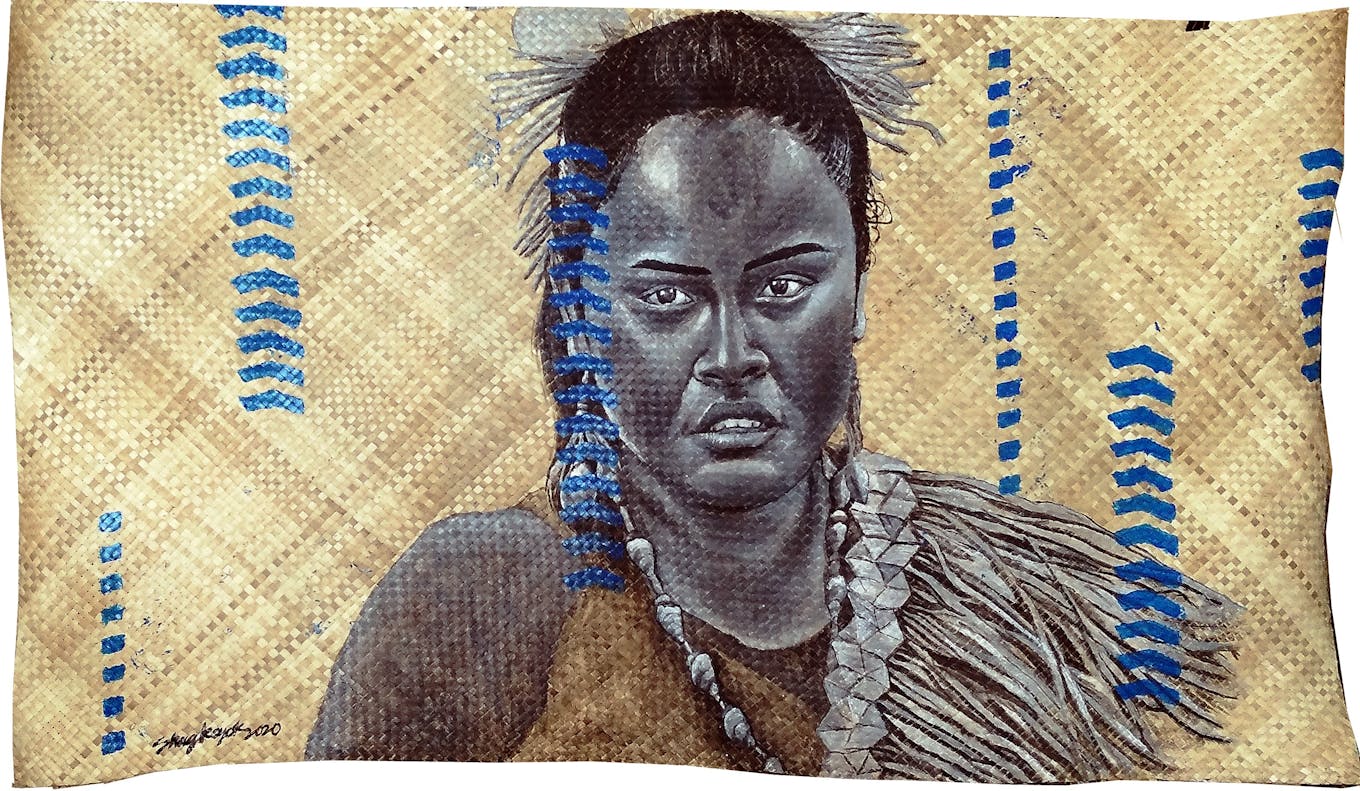

“Uncertainty”. Acrylic on Pandanous weaving. Indigenous peoples face ongoing threats from deforestation and land-grabbing in Malaysia. Image: Shaq Koyok

How do you feel about the passing of the Queen and what she means to Indigenous peoples?

I am not a big fan of the monarchy, whose wealth came from colonising other countries by a self-proclaimed race supremacy. It is scary knowing how many Indigenous people won’t be given the space to express how they feel about the Queen’s legacy and the impact of colonialism. Only after the Queen’s death, did people start talking and asking the “forbidden” questions.

Carbon markets have been billed as an invaluable way to save forests, but carbon deals have received criticism for excluding Indigenous peoples. What is your view?

We are dealing with the reality of carbon markets now in Malaysia, with the case earlier this year of two million hectares of forest in Sabah negotiated in a carbon trade without any consultation with the Indigenous groups who live there.

To me, this deal is just a money making scheme! And it seemed like easy money too for those involved. But the people who actually live on the land will suffer. The deal would mean that Indigenous people cannot access the forest. And for Indigenous people, without a connection to the forest, we lose our way of life, our livelihood and our culture. And that would have a huge impact in Sabah, because many Indigenous people live there.

“

Forests are where we are from. Forests have made us human. They have shaped us. If we lose forests, I believe humans will change into something different.

I don’t think carbon markets will help [fight climate change] – they will make it worse. Big polluting companies have released a lot of carbon into the atmosphere. But as long as they have money, it seems that they can buy land anywhere around the world to offset their pollution. An offset is then just a certificate that allows polluters to do more damage. The future is going to be very bleak if we rely on off carbon offsets and net-zero targets.

We need to change the system. Maybe I’m old fashioned, but I think there is a lot to learn from the Indigenous way of life, and finding balance with the ecoystem rather than exploiting it to make money.

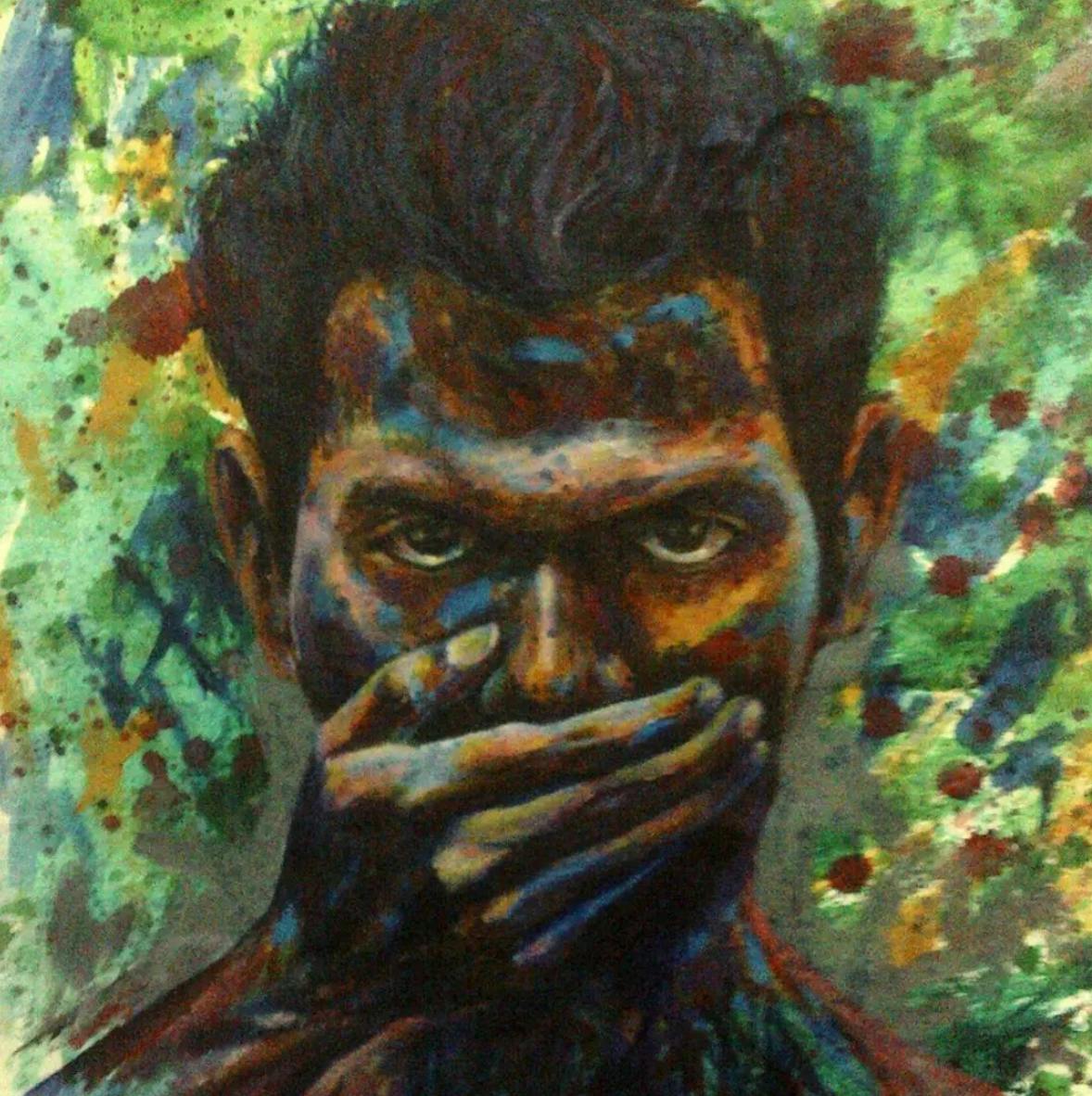

Indigenous peoples face numerous threats in Malaysia, including curbs to free speech. Image: Shaq Koyok

Give us some examples of what Indigenous peoples know about the forest that we could learn from.

My ancestors believe that our spirits pass into the forests when we die. We become part of the forest. That is one of the reasons why we have so much respect for forests. They are our brothers, our sisters, our family.

Our family members are often named after species of plants. Sometimes we give trees names. We give them food, we put clothes on them. They are considered part of the family.

Forests are where we are from. Forests have made us human. They have shaped us. If we lose our forests, I believe humans will change into something different – a different species.

The value in forests is so much more than just biodiversity. They hold knowledge and history. Going into the forest energises the body and frees the mind. It is no surprise that many studies show that going to the forest can ease depression.

“

Only after the Queen’s death, did people start asking the “forbidden” questions.

How do you find a balance between modern city life and village life in the forest?

Since the pandemic I have become more introverted. Because of the way I was brought up, I am really scared of infectious diseases, so I have avoided large gatherings over the past few years – and that’s new to me.

But generally, balancing modern and traditional life is not that difficult for me. I am proud of my culture but also proud of the knowledge I have gained from living in the city. My previous life, living in a village in the forest, shaped me and gave me roots to grow into what I’ve become. I have never felt ashamed to be an Indigenous person living in a city.

The reason why I live in the city is because I feel like I need to build a bridge between the city and the Indigenous way of life. There are so many gaps in the understanding of Indigenous life in Malaysia. Many Malaysians have never even heard of the Orang Asli people. Or if they have, they believe that we are all from Borneo.

Another reason I live in the city is that there is no wi-fi in the village! It is hard to make the voices of the Indigenous peoples heard without an internet connection. I want to be active in in representing Indigenous people’s rights, and Indigenous peoples rarely have a voice at the big events that decide the fate of the environment.

Shaq Koyok painting at home. Shaq lives in the city, where there is wi-fi. Image: Shaq Koyok

How hopeful are you for the future?

My people are careful in the way we think about the future, because we live from day to day and in the moment. We believe that we should not think too far ahead, or spirits will spoil our plans. For example, we never expect to be successful when hunting or collecting vegetables – or we won’t be. We try to just let what will happen, happen. So I am quite conflicted in how I feel about the future.

But I am optimistic. I am a glass-half-full kind of person. I believe that the damage the boomers [baby boomers] have done, zoomer [generation Z] will fix. We have had enough warnings of what is to come.