A handful of companies account for half of South American exports of major commodities—including soy, palm oil, cane sugar and cocoa—according to a new report by the Stockholm Environment Institute and Global Canopy. Soy production has expanded rapidly in Brazil, where exports are dominated by just six companies, with the majority of those exports feeding the ever-expanding Chinese demand for the oily bean.

The Trase Yearbook 2018 is the first in an annual series of reports tracking countries and companies involved in the trade of commodities such as soy, sugarcane, and maize, and assessing the deforestation risk associated with those crops, using data collated as part of the Transparency for Sustainable Economies (Trase) platform.

While the report itself is making news, so is Trase—a relatively new tool developed jointly by international non-profit organization (NGO) Stockholm Environment Institute(SEI) and Global Canopy to improve transparency in supply chains globally. Until the advent of Trase, the tracking of commodities by investors, environmentalists, economists, journalists, consumers and other interested parties was largely hit and miss. With Trase a commodities supply chain can often be identified with a couple mouse clicks.

Linking commodities to deforestation

Significantly, Trase offers “the first [ever] systematic accounting of the total deforestation risk associated with downstream buyers [for a particular] commodity that’s driving deforestation,” says Toby Gardner, Senior Research Fellow at SEI who heads the new platform.

Prior to Trase, publicly available data on supply chains was limited to national-level statistics, allowing only crude analyses that often failed to identify the companies involved.

“Trase has made an enormous contribution to increasing transparency in value chains and more specifically in soy in Brazil,” says Luis Fernando Guedes Pinto, Manager of Agricultural Certification at Imaflora, an NGO based in São Paulo, Brazil. “It is a revolutionary and useful tool for all actors involved in the trade of commodities.”

Trase was launched in 2016 and uses market research data on key commodities such as soy to track supply chains from the municipalities where the crops are produced, all the way to their international export.

Gardner hopes that the projects’ online visualizations and open-access data will “simplify what is an immensely complex picture into a very simple message,” for governments, companies, environmental NGOs and activists to act upon.

“

Trase offers “the first ever systematic accounting of the total deforestation risk associated with downstream buyers of a particular commodity that’s driving deforestation.

Toby Gardner, senior research fellow, Stockholm Environment Institute

The challenge of tracing soy

Soy production has expanded rapidly in South America in the last decade to meet growing market demand in Europe and Asia, largely for use as animal feed. Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay now provide almost half the world’s soy, up from just 3 per cent in 1975. Brazil is expected to overtake the United States as the world’s largest soybean producer this year, with Brazil expected to produce 117 million tons.

Commodities like soy are challenging to trace thoroughly along an entire supply chain because beans from many farms are typically trucked, bulked and aggregated at large centralized storage and sorting facilities. “There is no such thing as traceability of a [single] soybean,” says Gardner. For this reason, even commodities companies themselves often do not have full knowledge of their own supply chain sources.

To overcome this deficiency, Trase stitches together multiple datasets to identify “the most likely supply chain connections between a particular buyer and a particular landscape of production,” says Gardner. This estimation allows for the identification of landscape level effects, such as deforestation, which can then be more accurately allocated to specific traders.

Pinto warns that the strength of any particular Trase analysis depends on the availability of data. Gardner agrees, noting that Trase has performed particularly well for Brazil, where detailed data purchased from private market research companies could be combined with freely available data in government repositories and self-declared by companies.

As Trase expands its detailed analyses to other countries and commodities, analysts are encountering less complete datasets. Supply chains, they note, are more difficult to trace when commodities are exported not as raw crops, but as processed products. Argentina, for example, exports 80 per cent of its soy as soy cake or oil.

“I think a lot of people would be shocked [to learn] that the accessibility of many of the datasets we use was much greater in Brazil than for many European Union countries,” Gardner says. In the EU, import and customs data for individual shipments is not available in the public domain.

Tracking the global soy trade

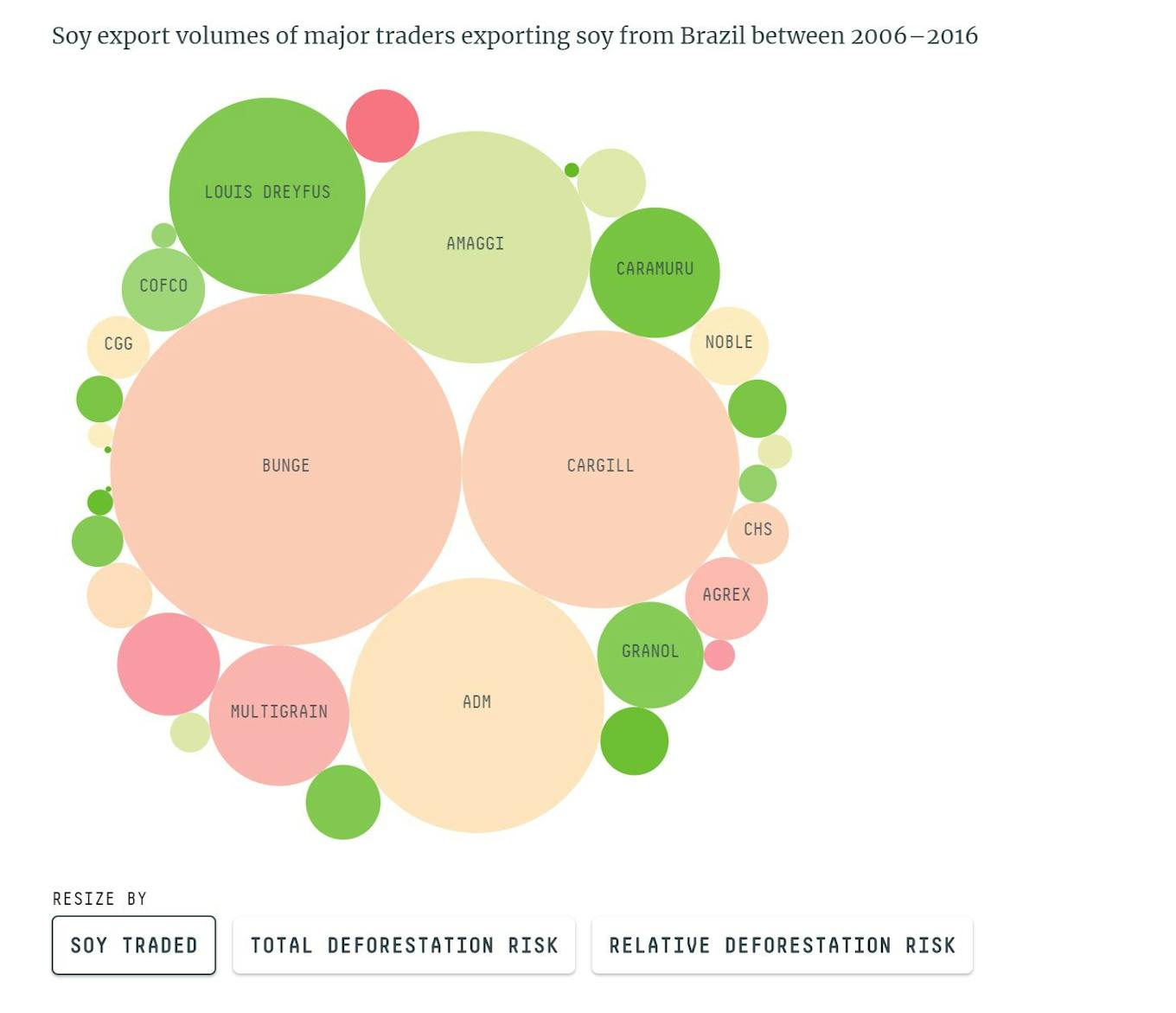

Although more than 1,000 companies exported soy from Brazil between 2005 and 2016, only a handful have commanded a significant share of the market. The Trase data shows that in 2016 it was dominated by just six key players—Bunge, Cargill, ADM, COFCO, Louis Dreyfus and Amaggi—which together accounted for 57 per cent of soy exported. Over the last decade, these six companies have also been associated with more than 65 per cent of the total deforestation in Brazil. None of the six companies responded to Mongabay’s requests for comment.

The dominance of so few very large companies “helps in pinpointing and targeting where the action is needed,” says Gardner, but “you’re dealing with a small number of incredibly powerful players,” which are unlikely to improve sustainability in their supply chains without governmental pressure and/or consumer willingness to pay a premium for that sustainability.

However, knowing the six principal soy traders linked to the bulk of deforestation could aid environmental NGOs in better targeting their campaigns as they try to implement a voluntary Soy Manifesto in Brazil’s Cerrado biome and maintain the Amazon Soy Moratorium.

One of the largest drivers of soy expansion across South America has been in demand from China, with exports increasing 300 per cent in the last decade, the Yearbook reports. China has increased their imports of Brazilian soy at the expense of exports from the U.S., Pinto says, which could have major ramifications for the future of sustainability in soy production. President Trump’s trade war with China could exacerbate shifts in soy trade patterns from the U.S. to Brazil. “We do not know the risks and sustainability consequences of these market battles,” says Pinto.

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com. Read the full story.