Less than two years after world leaders committed to end deforestation by 2030 at the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, forest loss is accelerating in the tropics.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

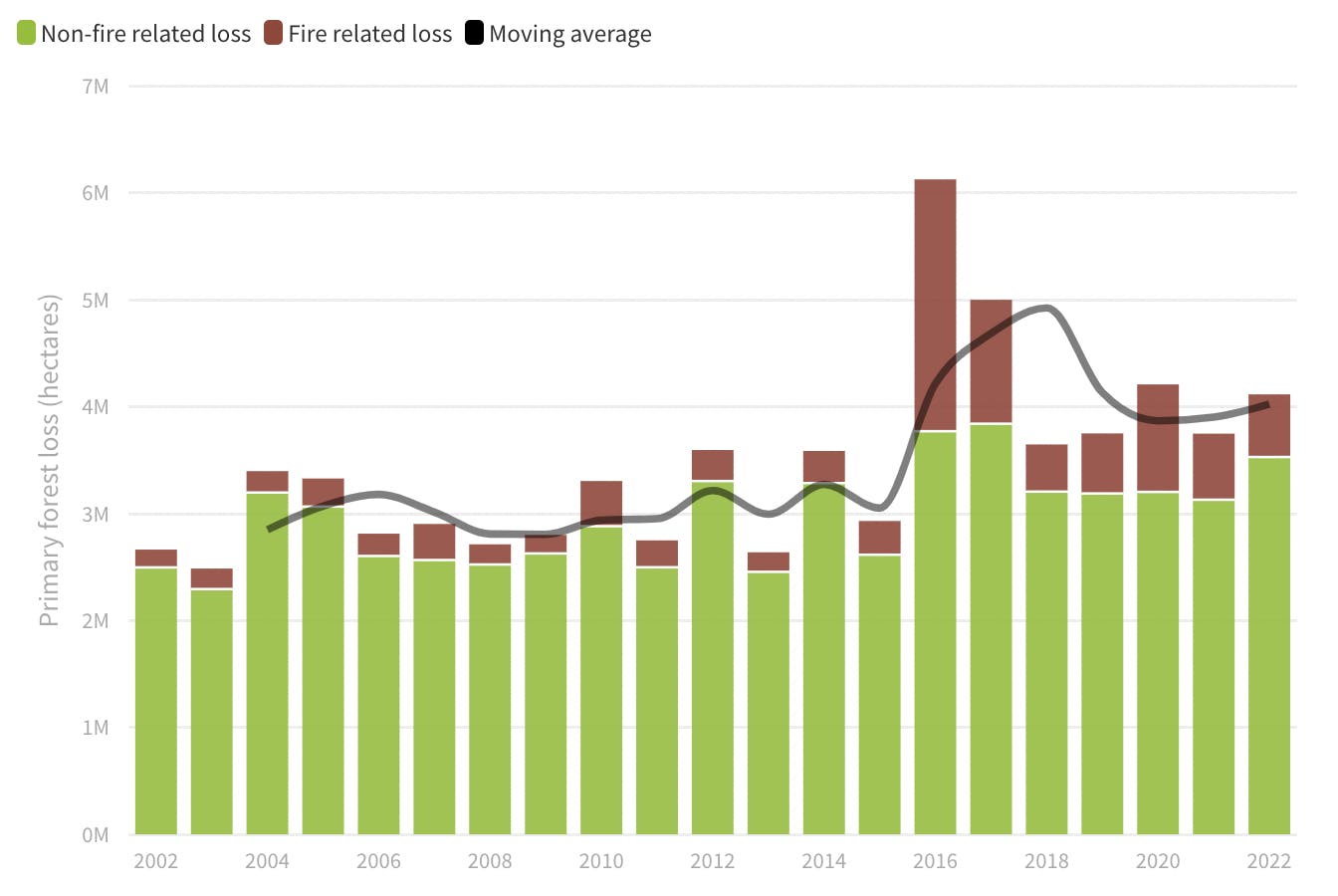

New data from Global Forest Watch (GFW), a non-profit that uses satellites to monitor deforestation, finds that 4.1 million hectares of tropical primary forest was lost in 2022. The climate cost of losing this much tropical tree cover is equivalent to producing 2.7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, a number that measures up to the annual fossil fuel emissions of India, the world’s third largest carbon polluter.

The tropics lost 10 per cent more primary rainforest in 2022 than in 2021, with the highest rates of deforestation occuring in Brazil under the administration of former president Jair Bolsonaro, nicknamed “Tropical Trump” and “Captain Chainsaw” for his policies that weakened protection of the Brazilian Amazon.

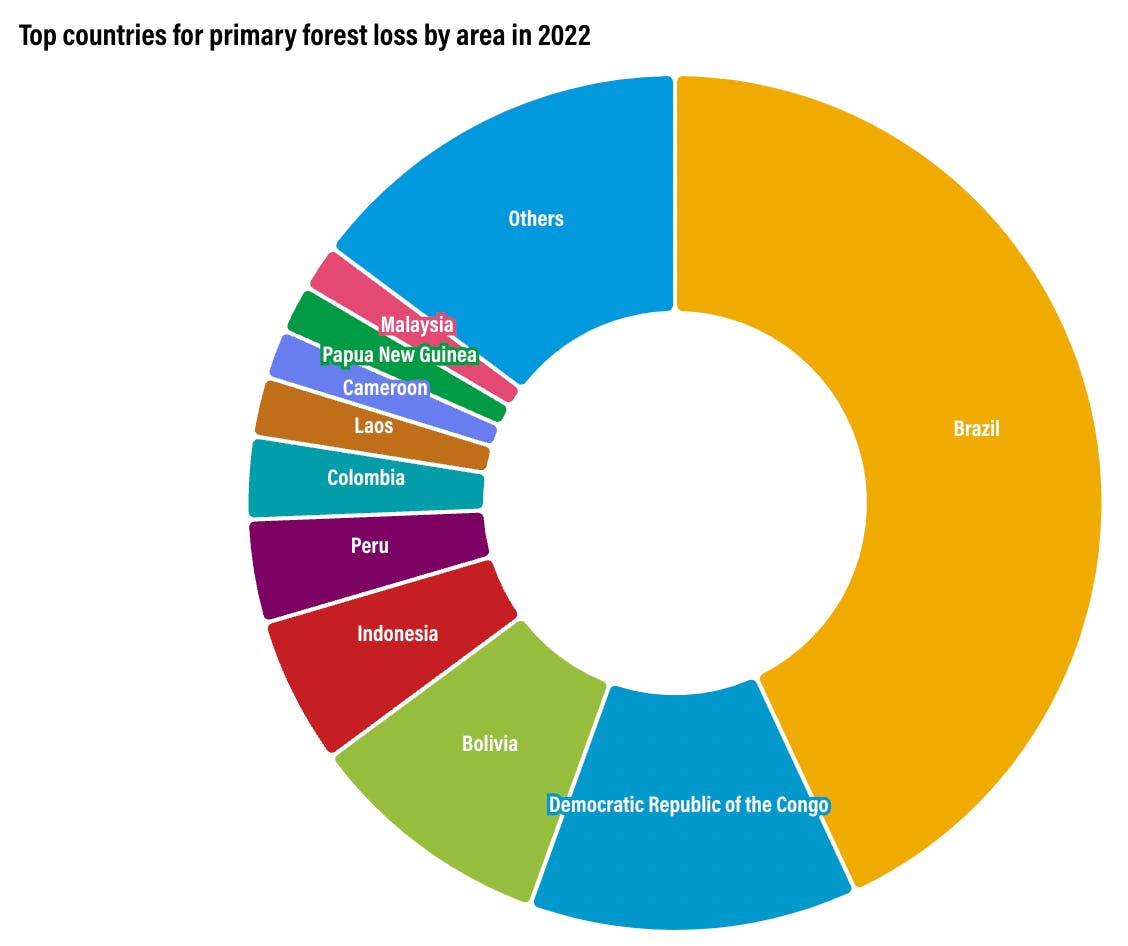

Forest loss from clear-cutting trees reached the highest level in the Brazilian Amazon since 2005. Brazilian forest loss accounted for 43 per cent of the global deforestation total last year. In October, Bolsonaro was unseated from power by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has pledged to restore protections for the green belt known as the “lungs of the planet” and achieve zero deforestation in the South American country by 2030.

Primary forest loss by country in 2022. [Click to enlarge] Source: Global Forest Watch

The highest increase in tropical deforestation occurred in the West African country of Ghana, which saw forest loss increase by 71 per cent year on year – a record high. Laos (31 per cent) and the Philippines (25 per cent) also featured in the top 10 countries with the biggest spikes in primary forest loss in 2022.

Indonesia in particular, and Malaysia – the world’s two biggest palm oil-growing nations – have managed to keep rates of primary forest loss to near record-low levels, according to GFW data.

Indonesia has seen deforestation fall by 64 per cent between the periods 2015-2017 and 2020-2022, the steepest drop of any tropical country. Over the same time frame, Malaysian deforestation has fallen by 57 per cent, the fourth steepest drop in the tropics.

In 2022, Indonesia, which has the world’s third largest tropical forest area, lost 107,000 ha of primary forest, the smallest area cleared since 2002, while Malaysia lost around 70,000 ha, with its rate of deforestation flat year on year.

Indonesia’s success in reducing deforestation has been attributed to tougher government policies on forest fire prevention and monitoring, peatland and mangrove rehabilitation, and climactic conditions – wet weather in recent years has helped minimise forest fires and primary forest loss.

Corporate commitments have also played a role in curbing deforestation in Indonesia, as they have in Malaysia. No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation (NDPE) commitments now cover the majority of the palm oil sector, while the pulp and paper industry – another major deforester – has also seen key pledges made to halt forest loss.

Mining is now Indonesia’s biggest deforesting sector, overtaking palm oil.

Malaysia and Indonesia have been using their recent track record in slowing deforestation as leverage to oppose the European Union’s newly introduced deforestation law (EUDR), arguing that because of their efforts to curtail forest loss, they should be allowed to access European supply chains.

Forest loss in the tropics between 2002 and 2022. Deforestation in 2022 was equivalent to losing 11 football fields of forest every minute. The brown bar indicates forest loss due to fire, the green bar indicates forest loss unrelated to fire. Source: Global Forest Watch

The cost of keeping forests standing

The chronic loss of tropical forests reflects an ongoing failure to find a way to pay to keep forests standing, said Dr Lahiru Wijedasa, Asia forest coordinator at BirdLife International, a conservation non-profit.

Emerging economies are cutting down forests as their populations and economies grow, he said. “There is an opportunity cost to leaving forests standing for governments in poor countries as they prioritise poverty reduction – and rich countries have not done enough to help them develop without cutting trees.”

Some industrialised countries, such as Norway, which has a deal to pay Indonesia to preserve its forests, have attempted to convince developing tropical nations that keeping forests standing is more profitable than cutting them down. The Reducing Emission from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) scheme, which emerged almost two decades ago, tries the same thing, and is seen as a cheap way to cut emissions. But in both cases, the promised finance did not materialise to a level that could compete with the economics of converting forest to other uses, said Wijedasa.

The voluntary carbon markets (VCM), where companies fund carbon removal through forest conservation to offset their emissions, may have started to slow deforestation in some countries, for instance Malaysia and Indonesia. VCM is a tool to allow the private sector to fund and fill the finance gap to keep forests standing. However, recent criticism over the credibility of VCMs in reducing emissions has stalled a potentially effective way to fund the conservation of forests at a time when the role of forests in climate change mitigation is well known, noted Wijedasa.

The trade in carbon credits could reduce the cost of countries meeting their climate goals by more than half by 2030, according to a recent study. But Wijedasa said that there may be insufficient natural areas to be sold on the carbon markets over the long term, and developing countries need to keep some nature-based solutions for themselves to meet their own climate goals.

GFW’s report emerges as Southeast Asia braces itself for a bout of haze airpollution caused by slash-and-burn farming and smouldering peatlands exploited for palm oil and pulp and paper production, mainly in Indonesia.

The return of the El Niño dry weather phenomenon could mean 2023 is a bad year for the haze and Southeast Asian forests.

Tropical forests are among the world’s most powerful carbon sinks, cooling the Earth’s surface by removing carbon dioxide from the air. Removing tropical forests, which have the highest biodiversity of any ecosystem on the planet, is the source of 12 to 17 per cent of man-made greenhouse gas emissions. Some 1.6 billion people, including 70 million Indigenous peoples, rely on tropical forests for their livelihoods.