Yokohama’s G30 plan was created in 2003 to address rising levels of solid waste generated by an increasingly affluent citizenry. After redesigning household waste streams and working closely with citizens and businesses, G30 proceeded to break all targets with the help of stakeholder cooperation and on-going public education, resulting in significant economic and environmental benefits.

The Challenge

Adjacent to Tokyo, Yokohama is the second largest city in Japan with a population of nearly 3.7 million. Like many Asian cities, it experienced a very rapid population expansion during the late 20th century, along with a subsequent deterioration of its urban environment. The city government had previously worked extensively with a wide range of companies and residents to introduce innovative approaches on land use regulation, urban design, service and infrastructure provisions, and to facilitate a win-win situation for all the stakeholders.

Even though population growth levelled off in the 1990s to 0.5-1% per year, Yokohama continued to generate more waste due to its economic development and lifestyle changes. This consumption-driven lifestyle put tremendous pressure on the city’s landfill durability.

The Solution

To reduce the environmental impact of incineration and landfill disposal, and to nudge the economy and society toward a zero-waste cycle, the city leadership initiated the G30 Plan in January 2003. Using fiscal year (FY) 2001’s 1.6 million tons of waste as a baseline, it aimed to reduce waste generation by 30% by FY2010. With strong trust built up through successful completion of previous collaborative projects, G30 was designed and implemented with the cooperation of business societies and the citizens. The goal was to realise a ‘sound material-cycle society’ where both the environmental impact, and energy and resource consumption was reduced. The idea was based on ‘polluter- pays’ and ‘extended-producer responsibility’ principles.

After identifying the responsibilities of the stakeholders, which were households, business societies and the government, the G30 Plan then stipulated that citizens, companies, and the city administration work together to promote the 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle). Citizens were required to adopt an environmentally-friendly lifestyle and participate in rigorous sorting of their garbage. Companies were encouraged to design and produce products which reduced waste emissions and enable environmentally-friendly disposal.

The city administration had to create social systems for the 3Rs, raise citizen awareness, and disseminate and exchange information.

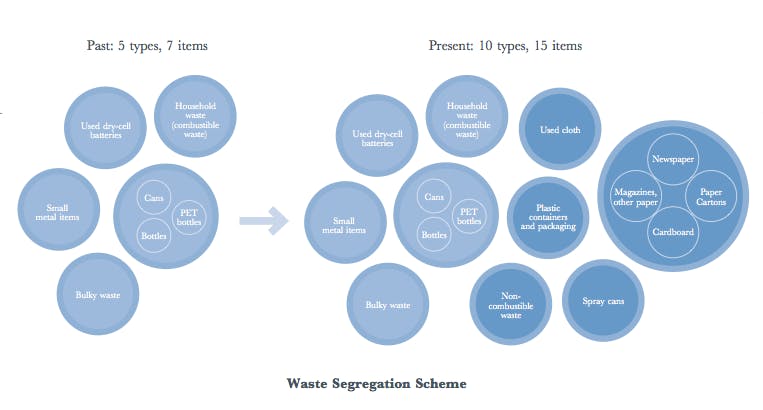

Existing combustible household waste was divided into more categories and a more active recycling scheme was implemented. The new recyclable items were segregated, collected separately and recycled through newly established or enhanced recycling business entities. Yokohama citizens were requested to separate waste into 15 categories and properly dispose of each one at designated places and times. Clear trash bags had to be used so that unsorted waste could be spotted easily.

Existing combustible household waste was divided into more categories and a more active recycling scheme was implemented. The new recyclable items were segregated, collected separately and recycled through newly established or enhanced recycling business entities. Yokohama citizens were requested to separate waste into 15 categories and properly dispose of each one at designated places and times. Clear trash bags had to be used so that unsorted waste could be spotted easily.

To disseminate the G30 approach and achieve the goals, the City conducted environmental education and promotional activities to enhance public awareness. More than 11,000 seminars were held over a two-year period at neighbourhood community associations (80% of Yokohama’s population are members) to explain how to reduce and segregate waste. About 600 campaigns were held at railway stations, and more than 3,300 awareness campaigns were organised at local waste disposal points. Campaign activities also took place at local shopping streets, supermarkets, and at various events. Local school and community based environmental groups were enlisted, to create a supportive and collaborative environment. Citizen volunteer ‘garbage guardians’ explained proper sorting measures to citizens and sought cooperation from those who were not supportive of the new segregation measures. The G30 logo was displayed on all city publications, city-owned vehicles, and at city events. A G30 mascot character was even created.

Initially, some citizens and businesses naturally resisted the new waste sorting rules, which were tougher to observe compared with pre-G30 standards. Since this was the priority project for the city’s leadership, public outreach and waste management rules were implemented consistently and firmly. At the same time, achievements, successful collaborations, waste reduction and financial information related to G30 were widely shared. With these efforts, businesses and citizens developed confidence in G30.

“

Garbage collection companies were instructed to return waste to firms and institutions if large volumes of inappropriate waste were discovered

The City did not pick up waste which was not properly sorted. For example, about 10,900 items per day were not collected in FY2009. The City introduced stricter inspections of private waste collectors and stopped receiving wood chips and recyclable paper at incineration plants. Garbage collection companies were instructed to return waste to firms and institutions if large volumes of inappropriate waste were discovered. While the City had the authority to impose fees and penalties for non-compliance, this rarely happened. In addition to the regulatory activities, the City continued to conduct public education outreach for students, and provide support for elderly and disabled people who had difficulty carrying waste to pick up points.

The Outcome

The figures speak for themselves. Yokohama’s 30% waste reduction target was achieved in FY2005, five years ahead of target. Despite the population growing by 170,000 people during this time, waste generation was reduced by 43.2% by FY2010. As a result of waste reduction, Yokohama’s two landfill sites still had 700,000 square metres in remaining capacity in 2007, thereby postponing development of new landfill sites. Yokohama also went from using seven incinerators in 2000 to just five in 2010 due to waste reduction. This saved US$1.38 billion in capital expenditure, and over US$7.5 million in annual operational expenditures. The waste that was reduced between FY2000 and FY2009 was also equivalent to avoiding 280,000 tons of CO emissions.

Stakeholders, particularly citizens and the private sector, playing an active role was key to the success of the effort. Substantial and consistent efforts were needed at grassroots levels to raise awareness and change behaviours. The measures in Yokohama did not require new technology or huge investments. This showed that local governments can count on citizen power once people understand the issues, change their behaviour, and become active players in implementing plans.

Yokohama’s new businesses profit by selling recyclables, such as cans, bottles, and papers. Some companies also transform paper and plastic into fuel. These recycling businesses are ready to launch operations regionally and globally, using green growth principles. International organisations such as The World Bank recognised Yokohama for balancing ecological achievement with economic development. Yokohama shares its experiences, expertise and technical knowledge with leading private sector firms through an initiative called Y-PORT; Yokohama Partnership of Resources and Technologies.

Yokohama now aims to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) to support Japan in its national GHG reduction target and demonstrate that it is an ‘Environmental Future City’. Further solid waste management is planned using the new ‘Yokohama 3R Dream Plan’, created in 2011, which will enable further solid waste reduction, using FY2009 as baseline to achieve 10% waste and resource use reduction, and 50% GHG reduction by 2025.

Mr Nobuya Suzuki, Deputy Mayor of Yokohama since April 2012, was born in 1955 and has been employed by the City of Yokohama since 1978. He wrote this article for Urban Solutions, an international magazine published by the Centre for Liveable Cities Singapore.