The research, published (free to access) this week in the journal Nature Energy, looks at what the agreement means for UK emissions both now and later this century. It is the first paper to apply a Paris-consistent carbon budget at the level of a single country.

It finds the UK will need a far more ambitious policy package in order to avoid using up more than its fair share of the remaining global carbon budget, with the most stringent case requiring it to achieve net-zero emissions by 2045.

Carbon Brief takes an in-depth look at the findings of the paper in the global context of the Paris deal.

‘Net zero’: the long-term goal

The 2015 Paris Agreement set a long-term goal to keep warming “well below” 2C. This will require an “overall balance” between sources and sinks of anthropogenic emissions – another way of saying net-zero emissions – sometime in the second half of this century.

The volume of greenhouse gases which can be released while still keeping a good chance of remaining below a certain global temperature rise is known as the carbon budget.

Current national emissions reduction pledges would breach the carbon budget for 2C, with one widely cited analysis estimating they will result in warming of close to 3C.

Most pledges – known in the UN jargon as NDCs, or nationally determined contributions – consider only 2025 or 2030 as their target time horizon.

What’s more, only a handful of countries so far – including Bhutan, Costa Rica and Norway – have commissioned government-backed national studies to explore net-zero transitions.

Therefore, there remains a large gap between the aspiration for an equitable global transition to a net-zero future, as set out in the Paris Agreement, and the national policy planning currently being carried out.

UK context

The UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act set a target of an 80 per cent cut in domestic greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 levels. It tasked the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) with giving guidance to the government on the lowest cost route to this goal.

This “80 per cent by 2050” target was based on scenarios with a 50/50 chance of remaining below 2C.

In the wake of the Paris deal, given its aim to stay “well below 2C”, the CCC said the UK would have to raise its ambition, including a net-zero emissions goal. But it said there was no need to make such changes for now.

Last March, then energy minister Andrea Leadsom confirmed the government’s commitment to enshrining a net-zero emissions goal in UK law, telling MPs “the question is not whether but how we do it”.

However, the new paper finds that putting off decisions about this long-term goal could lead to inadequate ambition in the near term as well as poor investment choices in energy infrastructure, if the ultimate goal of net-zero is to be met in time.

“This is the first paper that has applied this carbon budget-based approach over a post-2050 timeframe for a country-based analysis,” Steve Pye, senior research associate at the UCL Energy Institute and lead author of the paper, tells Carbon Brief.

“[W]e suggest that the UK should certainly consider the need for a net-zero emissions target post-2050, to help guide policy and investment decisions in large scale infrastructure. There would also be much merit in rethinking whether the current UK policy is ambitious enough, given the Paris Agreement.”

What the paper does

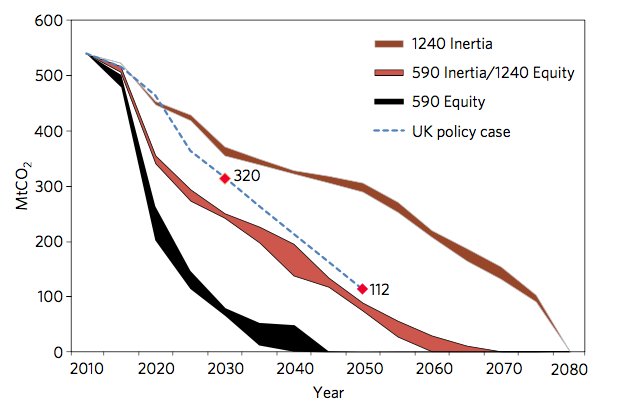

The new Nature Energy paper calculates the UK’s share of a Paris-compliant carbon budget and then asks what this would mean for domestic climate targets. It explores four different scenarios, which vary the ambition required from the UK.

The first two scenarios allocate global effort on a per-capita basis (described as “Equity”), while the second two apply effort evenly on current total global emissions, a system dubbed “Inertia” in the paper.

Since the UK’s per-capita emissions are currently relatively high, the equity approach results in a far more stringent target for the UK than the inertia case.

The paper looks at the range of global CO2 budgets consistent with a likely chance (66 per cent) of keeping warming below 2C. These are combined with the two different effort-sharing approaches. The four resulting scenarios are then compared to the UK’s current plans.

It also examines the implications of these scenarios for the Paris Agreement’s aspirational target of limiting warming to 1.5C.

Net-zero by 2045

The findings of the paper show that the most stringent combination of effort sharing and global carbon budgets would translate to a need for the UK to achieve a net-zero system by 2045, a significantly stronger level of mitigation than is currently set by UK policy.

This would require the UK to start cutting its CO2 emissions by an average of 9 per cent per year – far higher than the average 1 per cent year-on-year reduction it has achieved since 1990, the paper found (although note that the UK’s annual CO2 emissions cuts have averaged 6 per cent over the past three years).

Oil consumption would need to fall to around 20 per cent of current levels by 2030, while electrification would need to rapidly accelerate, driven by a rapid deployment of onshore and offshore wind.

A faster reduction in emissions from the transport and building sectors would also be needed, compared to current policy.

Overall, cumulative emissions up to 2050 would need to be two-thirds lower than implied by current legislation. This would add 20 to 30 per cent to the expected cost of meeting existing targets, reaching an additional £100bn over the years to 2030.

The model showed this scenario to be at the “limits of feasibility”, with many of the model runs limited by the difficulty of rapidly deploying low-carbon technologies, such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), in the near term.

“In short, the results put into sharp focus the need for a more ambitious policy package if equity-based budget cases are to be achieved,” the paper says.

These results also shed light on the possibility of the world achieving the aspirational Paris target of limiting global temperature rise nearer 1.5C, which would require yet faster cuts in emissions in the UK and elsewhere.

The paper concluded that achieving a net-zero energy system prior to 2050 appears “improbable”, barring an unprecedented fall in energy demand or radical breakthroughs in CO2 sequestration technologies.

“At the very best, this would require radical and immediate action across all sectors and a rapid shift away from fossil fuels, both of which are happening but at comparatively sedentary rates,” the paper says.

Raising 2050 ambition

The two central budget cases in the paper require net-zero emissions for the UK by 2070. However, this still translates to a need for higher ambition before 2050 than is currently set out in UK law.

Reaching net-zero by 2070 will only be possible if the transition starts much sooner, the paper says, while the remaining carbon budget still leaves space for flexibility. Otherwise, it argues, there is a “real risk” that action taken by 2050 will fall short of staying within the implied carbon budget of the Paris Agreement.

“We conclude that strategic national energy system planning, even in the short term, requires analysis with a post-2050 time horizon that appropriately reflects global climate ambition,” the paper reads.

These two “zero-by-2070” scenarios would require an average 4% drop in CO2 emissions per year, raising costs by 2-3% compared to the UK’s current path.

Net CO2 emissions from the UK energy system under the Paris Agreement, based on “Equity” and “Inertia” allocations of effort. The global CO2 budget is set as either 590 or 1,240 Gt after 2015 – the outermost limits for a likely chance of 2C used in the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. 590 Inertia and 1240 Equity are shown together as they have the same trajectory. The red markers in the current UK policy case show CO2 emissions in line with the Climate Change Act for 2030 and 2050. Source: Pye et al., (2017)

“[W]e suggest that the UK should certainly consider the need for a net-zero emissions target post-2050, to help guide policy and investment decisions in large scale infrastructure.

There would also be much merit in rethinking whether the current UK policy is ambitious enough, given the Paris Agreement,” Pye tells Carbon Brief. (A decade ago, Pye authored some of the main early assessments of the cost of implementing the UK’s Climate Change Act.)

Uncertain world

Planning for a net-zero budget would also need to account for the fact that the UK faces significant uncertainties over how it will be able to cut emissions.

For example, while CO2 can be more or less directly correlated with global temperature rise, the remaining global budget of CO2 for a 2C target will be influenced by the levels of non-CO2 greenhouse gases emissions.

A second uncertainty facing the UK is the availability of low-carbon technologies, such as CCS and nuclear, needed to deliver significant decarbonisation. Staying within budget levels without CCS would be “extremely challenging”, the paper says, in line with the opinion of the CCC.

The UK will also likely need negative emissions technology to compensate for sectors which are difficult to decarbonise, such as international transport and agriculture.

However, the practicality of negative emissions strategies remains contested. With bioenergy with CCS (BECCS), for example, questions remain both over its technical feasibility and the availability of future bioenergy resources.

Another uncertainty is how far it will be possible to reduce demand for energy in heating, transport and lighting.

Rapid decarbonisation scenarios rely heavily on energy efficiency, which does not require the large scale investment or infrastructure build needed for other kinds of mitigation. However, it is hard to know in advance the levels possible.

Timely research

Professor Corinne Le Quéré, director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia, says the paper is “timely” and makes it “very clear” that even steep and deep emissions reductions will not be sufficient unless accompanied by a net-zero emissions strategy. Le Quéré tells Carbon Brief:

“This is difficult, however, and whereas Pye and co-authors make a convincing case of why we need to set in place measures to achieve net-zero emissions post-2050, at the moment for the UK, we do not know how this would be achieved.

“Setting out a strategy to remove greenhouse gas from the air is critical for successfully tackling climate change. I would still, however, prioritise rapid and deep cuts in emissions now, because they work and they keep options open.”

In an accompanying article on the paper also published in Nature Energy this week, Dr Alessandro Tavonim, researcher in environmental economics at LSE, praised the article for filling a research void in assessing the adequacy of national targets for reaching net-zero emissions.

However, he highlighted several real-world complications of the scenarios, including the possibility of more stringent targets in the UK resulting in “free-riders” elsewhere, as well as the distortions in global burden sharing which can arise from powerful nations having more bargaining ability or through the influence of lobby groups.

Conclusion

While 2050 and beyond may seem a long way off, the paper uses the UK as a case study to show how the time horizon of most current climate pledges – typically 2025 or 2030 – could raise the risk of technological “lock-in” after this time, with system configurations unsuited for the long-term net-zero goals required under the Paris Agreement.

It finds that the UK will likely need a far more ambitious policy package than is currently planned if it is meet its share of responsibility under the Paris deal, reaching net-zero no later than 2070.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.