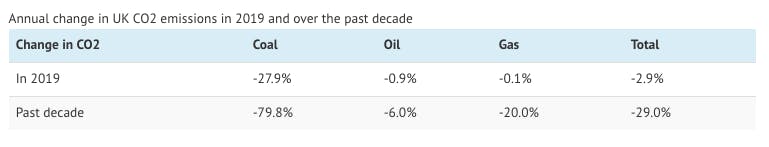

The UK’s CO2 emissions fell by 2.9 per cent in 2019, according to Carbon Brief analysis. This brings the total reduction to 29 per cent over the past decade since 2010, even as the economy grew by a fifth.

Another 29 per cent reduction in coal use last year was the driving force behind the decline in UK emissions in 2019, with oil and gas use largely unchanged. Carbon emissions from coal have fallen by 80 per cent over the past decade, while those from gas are down 20 per cent and oil by just 6 per cent.

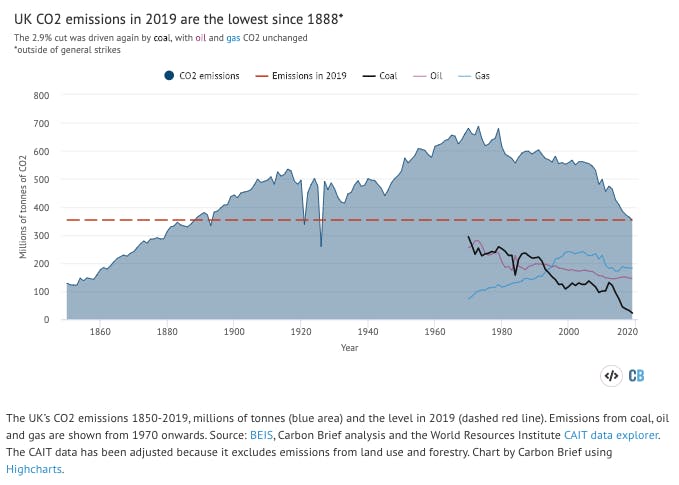

The 2.9 per cent fall in 2019 marks a seventh consecutive year of carbon cuts for the UK, the longest series on record. It also means UK carbon emissions in 2019 fell to levels last seen in 1888.

The analysis comes as the UK – and the world – enter what needs to be a “decade of action” in the 2020s, if global goals to limit rising temperatures are to be met. Ahead of the COP26 UN climate summit this November, countries are expected to submit enhanced pledges to tackle emissions.

But UK government projections show the country will miss its legally binding carbon targets later this decade. To meet the UK’s carbon budgets, CO2 emissions would need to fall by another 31 per cent by 2030, whereas government projections expect just a 10 per cent cut, based on current policies.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC), which is the UK government’s official climate advisory body, has also said the UK’s targets over the next decade are “likely” to be insufficient, given the increased goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

Annual decline

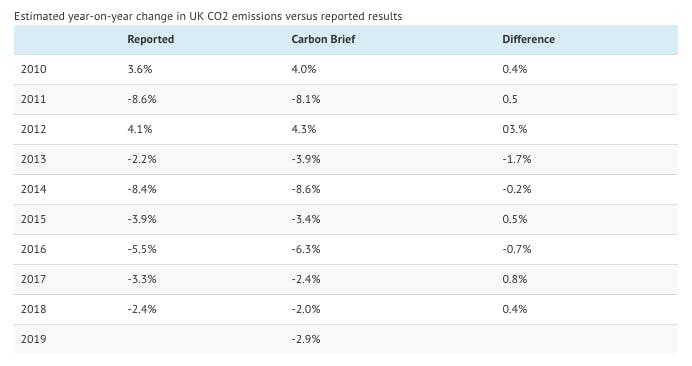

Carbon Brief’s provisional estimates suggest that the UK’s CO2 emissions fell by another 2.9 per cent in 2019, once again driven primarily by falling coal use, as shown in the table, below.

The bulk of the reduction in coal use last year came from the power sector, which accounted for 93 per cent of the overall fall in demand for the fuel in 2019. The remainder was from industry.

Coal generation fell by close to 60 per cent and accounted for just 2 per cent of UK electricity last year – less than solar. Fossil fuels collectively accounted for a record-low 43 per cent of the total, according to Carbon Brief analysis published at the start of January. Some 54 per cent of electricity generation in the UK is now from low-carbon sources, including 37 per cent from renewables and 20 per cent from wind alone.

There were 83 days in 2019 when the UK went without coal power, including a record 18-day stretch in May. Almost all of the UK’s remaining coal power plants have announced plans to close over the next 12 months, leaving just three operating ahead of the 2024 government deadline.

Carbon Brief’s emissions analysis shows that CO2 from burning gas remained virtually unchanged during 2019. The fuel is now the single-largest contributor to UK emissions, ahead of oil.

Gas demand for electricity generation, as well as demand to heat homes and businesses, were relatively flat, with 2019 seeing similar temperatures to those in 2018. (Both years were around 0.5C above the long-term average for 1981-2010.)

Oil demand and emissions fell by nearly 1 per cent in 2019, Carbon Brief’s analysis suggests. This is despite rising road traffic, up 0.8 per cent in the year to September 2019, according to separate government figures published in December.

The UK’s vehicle fleet is changing under several competing influences, with electric vehicle sales surging and diesel cars losing out to petrol in the wake of the Volkswagen emissions scandal.

Meanwhile, a broader global trend towards heavier vehicles, such as SUVs, means that the average CO2 emissions per mile for new UK cars has been increasing for three years. Notably, the relative mix of traffic from private cars, vans and trucks is also shifting, as discussed below.

Past decade

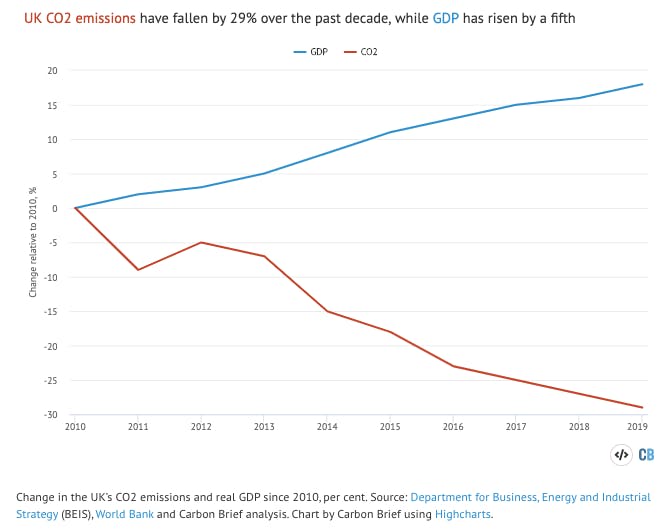

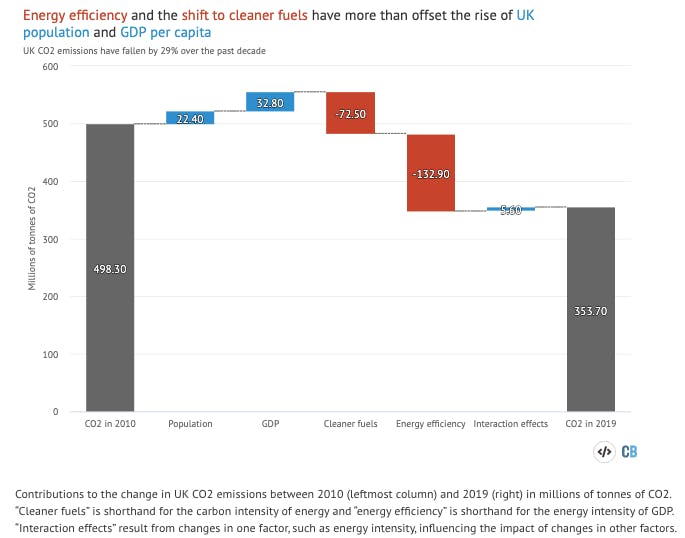

Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that the UK’s CO2 emissions have fallen by 29 per cent over the past decade since 2010, the year when the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government took office. At the same time, the UK’s economic output has risen by 18 per cent, as the chart below shows.

Looking at international data up to 2018 – the most recent year available – the UK has seen the fastest decline in CO2 emissions of any major economy. Only the US has seen larger absolute cuts than the UK, in terms of tonnes of CO2 over this period, but its 5 per cent decline is smaller in percentage terms.

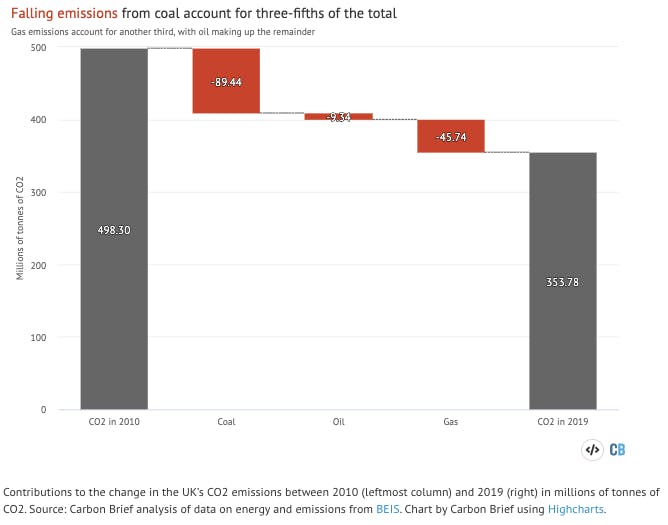

The UK’s CO2 emissions in 2019 stood at an estimated 354 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2), some 41 per cent below 1990 levels.

This places the UK in between Australia (421MtCO2 in 2018) and Poland (344MtCO2). The UK’s per-capita CO2 emissions in 2019, at 5.3tCO2, are above the global average (4.8 in 2018) and India (2.0), but below the EU average (7.0) and the figure for China (7.2) or the US (16.6).

Almost all of the recent progress on UK emissions has come in the power sector, which has seen dramatic changes over the past decade. Coal use to generate electricity has plummeted thanks to reductions in demand and the rise of renewables, while gas power has also fallen slightly.

By way of illustration, the chart below shows that coal accounts for around three-fifths of the decline in UK CO2 emissions over the past decade. The vast majority of this – some 89 per cent – is due to falling coal use in the power sector. (Coal use in the steel industry has halved, accounting for a further 8 per cent of the decline in coal emissions over the past decade.)

In order to meet climate goals towards 2030, the UK’s CO2 emissions will need to fall another 31 per cent from 2019, compared with the 29 per cent achieved over the past decade. Emissions would need to fall even faster if the targets are raised in line with net-zero by 2050. In contrast, government projections suggest CO2 emissions will only fall by a further 10 per cent by 2030.

(Carbon Brief estimates that UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 were some 45 per cent below 1990 levels, against a target of 61 per cent for the five years covering 2028-2032.)

Moreover, coal’s share of the UK electricity mix is now so low that there is very limited scope to continue driving emissions cuts by reducing use of the fuel. This means other, more visible sectors of the economy will need to make progress for the UK to continue hitting its legally binding goals.

As the chart above shows, the past decade has seen much more limited progress in cutting emissions from oil (down 6 per cent) or gas (20 per cent), with these fuels broadly associated with transport (oil) and space heating in homes or offices (gas).

Domestic gas use has declined by 20 per cent since 2010, thanks to improvements in the energy efficiency of homes and regulations driving a shift to more efficient condensing boilers. Yet the majority of homes remain far short of the government’s aspirational target for higher efficiency and UK properties are among the least-well insulated in Europe.

Gas use for electricity generation has also fallen by 25 per cent over the past decade, even as coal generation has collapsed, thanks to reduced demand and the rise of renewables.

Emissions from oil use have remained relatively unchanged over the past decade. This is largely due to transport, which is now the single largest source of UK CO2 emissions on a sectoral basis. The country’s cars are now responsible for more CO2 than the entire power sector, for example.

Although oil emissions have changed little over the past decade, this conceals some significant shifts within the transport total, thanks to shifting driving patterns and modest improvements in fuel efficiency over time.

For example, the number of miles driven by cars has increased by around 5 per cent over the past decade, while CO2 emissions from cars have fallen by 3 per cent.

Meanwhile, the number of miles driven by “light duty vehicles”, such as delivery vans, has shot up by 23 per cent in a decade, corresponding to a 20 per cent rise in CO2 emissions.

Vans and trucks together make up around a third of all UK emissions from transport, with cars adding another 55 per cent and the remainder coming from domestic aviation, shipping and railways.

Historical trend

After a record seven consecutive years of decline, the UK’s CO2 emissions are now some 41 per cent below 1990 levels. Outside years with general strikes, seen clearly in the chart, below, this is the lowest level since 1888, when the first-ever Football League match was played and Tower Bridge was being built near what is now Carbon Brief’s office in London.

Although no other country in the world has achieved similar reductions, it is worth emphasising that the UK was the first to industrialise. As such, its cumulative historical emissions still rank as the fourth-highest in the world.

Reasons for change

If the UK’s energy system had remained unchanged over the past decade, then the country’s rising population and economic growth would have driven emissions higher, rather than lower.

This is shown in the chart, below, which breaks down the reasons for the dramatic reduction in emissions that has actually occurred.

The largest contributor to falling emissions over the past decade has been improvements in energy intensity, which is the amount of energy needed to produce each unit of GDP. Broadly speaking, this reflects the fact that the UK has become much more energy efficient.

The second-largest contributor has been a shift to cleaner fuels, primarily renewable sources of electricity. Together, these effects have more than offset the impact of rising population and GDP.

The various factors in the chart above are estimated from a “Kaya identity”, according to which emissions are the product of population, multiplied by GDP per capita, multiplied by the energy intensity of GDP, multiplied by the CO2 intensity of energy.

CO2 = P x GDP/capita x energy/GDP x CO2/energy

To calculate the relative contributions to changing emissions, each factor is systematically varied while holding other elements constant. For example, the Kaya identity can be used to estimate what UK CO2 emissions would have been in 2019, if population had remained at 2010 levels.

As noted in the caption to the figure, above, the chart labels are a shorthand. Specifically, changes in the energy intensity of GDP, labelled as “energy efficiency”, are a reflection of genuine demand reductions – due to more efficient products and processes – but they also reflect the increasing share of energy coming from renewable sources.

This is because a large part of the “primary energy” contained in raw fossil fuels – a lump of coal, for example – is lost as waste heat when the fuel is burned to produce useful energy. The same is not true of electricity from windfarms or solar panels, which, therefore, has a lower energy intensity.

Carbon Brief calculations

Carbon Brief’s estimates of the UK’s CO2 emissions in 2019 are based on analysis of provisional energy use figures published by BEIS on 28 February 2020. The same approach has accurately estimated year-to-year changes in emissions in previous years (see table, below).

One large source of uncertainty is the provisional energy use data, which BEIS revises at the end of March each year and often again later on. Emissions data is also subject to revision in light of improvements in data collection and the methodology used.

The table above applies Carbon Brief’s emissions calculations to the latest energy use and emissions figures, which may differ from those published previously.

Another source of uncertainty is the fact that Carbon Brief’s approach to estimating the annual change in CO2 output differs from the methodology used for the BEIS provisional estimates. This is largely because BEIS has access to more granular data, which is not available for public use.

However, Carbon Brief understands that its methodology has over the past year been used to improve the early “pre-provisional” estimates produced by the department for internal use, prior to the release of full provisional figures at the end of March each year.

In Carbon Brief’s approach, UK CO2 emissions are estimated by multiplying the reported consumption of each fossil fuel, in energy terms, by its emissions factor. This is the amount of CO2 released for each unit of energy consumed and it varies for different fuels.

For example, diesel, petrol and jet fuel have different emissions factors and Carbon Brief’s analysis accounts for this where possible. This adjustment is based on the quantity of each fuel type used per year, drawn from separate BEIS figures covering oil, coal and gas.

Emissions from land use and forestry are assumed to remain at the same level as in 2018. This year, Carbon Brief adopted the BEIS approach to estimating the change in emissions from greenhouse gases other than CO2.

Note that the figures in this article are for emissions within the UK measured according to international guidelines. This means they exclude emissions associated with imported goods, including imported biomass, as well as the UK’s share of international aviation and shipping.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has published detailed comparisons between various different approaches to calculating UK emissions, on a territorial, consumption, environmental accounts or international accounting basis.

The UK’s consumption-based CO2 emissions increased between 1990 and 2007. Since then, however, they have fallen by a similar number of tonnes as emissions within the UK. Carbon Brief estimates that consumption-based CO2 emissions fell by around 21 per cent over the past decade.

Bioenergy is a significant source of renewable energy in the UK and its climate benefits are disputed. Contrary to public perception, however, only around one quarter of bioenergy is imported.

International aviation is considered part of the UK’s carbon budgets and faces the prospect of tighter limits on its CO2 emissions. The international shipping sector recently agreed to at least halve its emissions by 2050, relative to 2008 levels.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.