The latest round of national climate pledges falls “far short of what is required” to achieve the targets set out in the Paris Agreement, according to new UN analysis.

A new “synthesis report” from UN Climate Change examines the combined impact of the 48 new and updated “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) submitted by its end-of-year deadline.

Countries were meant to set more ambitious targets by the close of 2020, but the report shows that, overall, the level of ambition has only increased slightly.

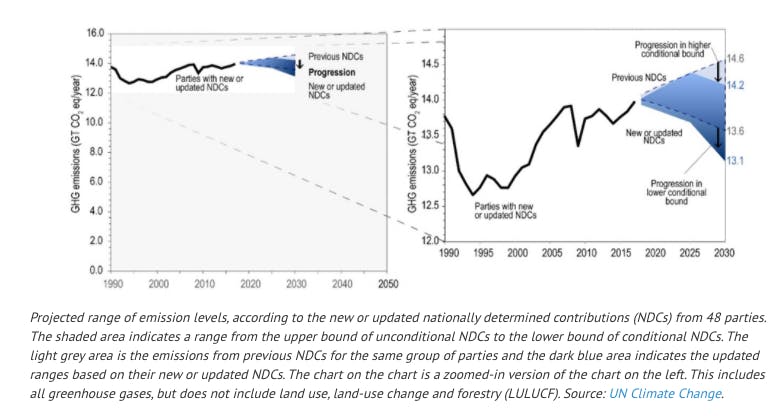

The combined emissions cuts of the new pledges are only around 3 per cent lower by 2030 than the previous round of pledges submitted by those nations in 2015.

Furthermore, with these targets in place their combined emissions would be just 0.5 per cent lower in 2030 than in 2010 and 2.1 per cent lower than in 2017– far off the 45 per cent reduction in total CO2 emissions from 2010 scientists have said is required to keep warming below 1.5C.

With most of the world’s biggest emitters – notably, the US and China – still yet to release new NDCs nearly two months after the deadline passed, the report emphasises “the need for parties to further strengthen their mitigation commitments”.

(For more information on the new NDCs, their level of ambition and climate finance requirements, Carbon Brief analysed the nations that met the end of year deadline in a separate article published last month.)

More ambition needed

Every party signed up to the Paris Agreement is committed to submitting an NDC, which they then have to renew or upgrade within five years under the so-called “ratchet mechanism”.

This is important because the first round of NDCs were far off what is required to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming since the pre-industrial era to “well below” 2C, let alone its stretch target of 1.5C.

Although many nations have stated that their targets are consistent with Paris Agreement goals, the UN points in its new report to the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

According to the IPCC, a 45 per cent reduction in global CO2 emissions between 2010 and 2030 is required to meet the temperature goal of 1.5C – and a 25 per cent reduction is needed to stay below 2C of global warming. There are also deep reductions required for non-CO2 emissions.

However, the new report finds that the total emissions of nations that had come forward with new pledges would be just 0.5 per cent lower in 2030 than in 2010 and 2.1 per cent lower than in 2017. The report states:

“While noting that this synthesis of information covers only about 40 per cent of the parties to the Paris Agreement, the collective scale of reduction expected to be achieved, for those parties considered, through the implementation of new or updated NDCs falls far short of the IPCC ranges.”

On an individual basis, the UN says in its new synthesis report that many parties have, in fact, “increased ambition to address climate change”.

In an accompanying press release, COP25 president Carolina Schmidt notes that the UK and the EU have committed to a “strong increase” in their reduction targets.

However, even with this enhanced ambition, the total emissions expected within a decade from these nations are set to be just 2.8 per cent, or 398MtCO2e, lower than their initial pledges. This amounts to around 0.8 per cent of total global emissions today.

This small improvement can be seen in the chart below, with further progress possible if some nations’ extra “conditional” targets are accounted for.

Conditional targets tend to rely on richer countries providing help, such as extra climate finance (see above), as well as other factors, such as how much CO2 forests can absorb. The number of unconditional targets in new NDCs has increased by around 5 per cent.

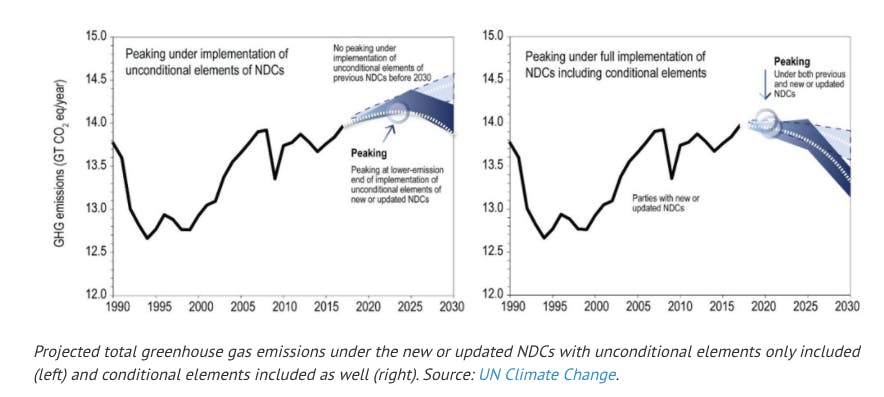

Unlike the previous set of NDCs published in 2015, the new round could see emissions from these nations peaking before 2030, especially if the conditional elements are included. This can be seen in the chart below.

Improved coverage

The synthesis report is made up of information drawn from 48 NDCs, including one from the EU and its 27 member states.

The total emissions from these nations in 2017 is estimated to be around 14GtCO2e, which is just 29 per cent of the global total.

This is three more NDCs than Carbon Brief accounted for in its own analysis published last month owing to the inclusion of Ecuador, Uruguay and North Korea, which collectively account for around 0.4 per cent of global emissions.

It is unclear why the UN included the two Latin American nations as they have both only submitted one NDC.

It may be related to an arcane procedure by which nations can request their original intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) not be automatically converted to official NDCs. Carbon Brief has asked for clarification on this discrepancy.

North Korea’s 2019 update had been excluded by the Climate Watch and Climate Action Tracker databases Carbon Brief used in its analysis, although both have been updated in light of the UN report. This may be due to a lengthy delay between it being submitted and added to the UN registry.

Since the end of 2020 there have been new NDCs submitted by Iceland, St Lucia and South Sudan, but these were not included in the UN’s analysis.

There has been an overall increase in coverage by nations’ climate pledges, with 99.2 per cent of their economies covered, up from 97.8 per cent in the previous round of NDCs from these countries.

Some nations exclude certain sectors of greenhouse gases because they are deemed “negligible”, or because they lack the technical capacity to monitor them, according to the report.

Nevertheless, the number of parties communicating economy-wide targets has also increased by around 8 per cent, with many NDCs also including components addressing adaptation to climate impacts.

The difference in coverage between the first and second rounds of NDCs can be seen in the charts below, which show different sectors and greenhouse gases.

The number of parties stating they would use “voluntary cooperation” – primarily, carbon markets – under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement to meet their targets nearly doubled compared to the first NDCs.

With the rules around Article 6 still to be decided and many concerned that the trading of emissions could undermine the Paris Agreement, it is notable that many NDCs also included limits on participating in such markets and commitments to high standards.

‘Red alert’

Almost all parties communicated an NDC implementation period until 2030 as was required in this new round of pledges.

However, a few still used 2025 as their target year and some nations also included targets for 2050.

Many parties mentioned long-term targets that referenced net-zero emissions or carbon neutrality. While “noting the inherent uncertainties in such long-term estimates”, the UN’s report concludes that following such plans could cut their emissions by 80-90 per cent by 2050.

While there has been a recent wave of pledges to reach net-zero by 2050 or 2060, the point of updating NDCs is to set ambitious, short-term targets, as US climate envoy John Kerry told a recent UN security conference:

“It is simply not acceptable…for countries to think they can go to [COP26] and simply put big numbers out for projections – 30 or 40 years from now or longer. It’s what people will do in the next 10 years that matter.”

In a statement, UN secretary-general, António Guterres said:

“Today’s interim report from the UNFCCC [UN Climate Change] is a red alert for our planet. It shows governments are nowhere close to the level of ambition needed to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.”

The US itself is still yet to announce its new NDC, but president Joe Biden is convening a meeting of world leaders from major economies on 22 April to ramp up the pressure on climate action.

Meanwhile, China, the world’s largest emitter, has signalled it will increase the ambition of its NDC, but has yet to formally submit it. Other major economies including India, Indonesia and Canada are also yet to come forward with theirs.

As captured in Carbon Brief’s recent coverage, not only have nations such as Japan, South Korea and Russia not scaled up their ambition with their new NDCS, other major economies – namely Brazil and Mexico – have actually scaled back their ambition.

Sofia Gonzales-Zuñiga, a climate policy analyst at NewClimate Institute who works on analysing NDCs for Climate Action Tracker (CAT), tells Carbon Brief:

“Despite the situation now, there is everything to play for by Glasgow. The countries that have so far not put forward changes and ambition could be embarrassed into further action once the major players step forward and many will be placed under diplomatic pressure to do so.”

The UN has said it will prepare a more comprehensive synthesis report ahead of COP26 when additional NDCs have been released.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.