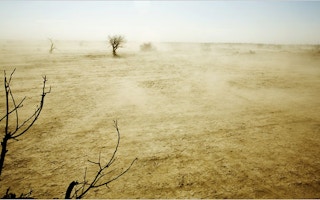

Water scarcity is a fact of life in many parts of the world, particularly in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa. A new study says the situation could get a lot worse, with climate change resulting in less rain and more evaporation in many areas.

The study, led by researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact and Research and appearing in the journal Environmental Research Letters, looks at present commitments by countries to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs). It says that even if these commitments or pledges are met, the global mean temperature will still rise by around 3.5°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

This, according to the researchers’ calculations, will expose 668 million people worldwide to new or aggravated water scarcity – that’s in addition to the 1.3 billion people already at present living in water-scarce regions.

Using the same calculations, the study says that if the global mean temperature rises by only 2°C, at present the internationally agreed target maximum, an additional 486 million people – a figure equivalent to more than 7% of the world’s present population – will be threatened with severe water scarcity.

Regions which will see the most significant deterioration in water supplies are the Middle East, North Africa, southern Europe and the south-west of the US.

Dr Dieter Gerten, the study’s lead author, says the main factor leading to more water shortages will be declining precipitation: increasing temperatures will also lead to greater evapotranspiration – that is the sum of evaporation and plant transpiration from the Earth’s land surface to the atmosphere.

“Even if the increase is restricted to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, many regions will have to adapt their water management and demand to a lower supply, especially since the population is expected to grow significantly in many of these regions”, says Gerten.

Recognising the impacts

It’s vital, says the study, that governments and policymakers, when setting targets on temperature rises, are fully informed of the overall consequences of their decisions.

“The unequal spatial pattern of exposure to climate change impacts sheds interesting light on the responsibility of high-emission countries and could have a bearing on both mitigation and adaption burden-sharing”, says Gerten.

The Potsdam study used material from 19 different climate change models. This was run alongside eight different global warming trajectories. In all more than 150 climate change scenarios were examined.

Researchers also examined the impact future changes in climate would have on the world’s ecosystems, seeking to identify which areas would be subject to greatest change and whether these regions were rich in biodiversity.

“At a global warming of 2°C, notable ecosystem restructuring is likely for regions such as the tundra and some semi-arid regions”, says Gerten.

“At global warming levels beyond 3°C, the area affected by significant ecosystem transformation would significantly increase and encroach into biodiversity-rich regions.

“Beyond a mean global warming of 4°C, we show with high confidence that biodiversity hotspots such as parts of the Amazon will be affected.”