It is not often that a palm oil company executive has nice things to say about an environmental campaign group snapping at its heels to improve how it does business.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But for Anita Neville, chief sustainability and communications officer for one of the world’s biggest palm growers, Sinar Mas-owned Golden Agri-Resources (GAR), Mighty Earth, a Washington DC-headquartered non-government organisation, stands out among its peers in two important ways.

The first is how it engages with rogue suppliers to help them get back into the supply chain.

Mighty Earth was “constructive and pragmatic while still principled” in its dialogue with suppliers that were non-compliant with GAR’s No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation (NDPE) policy, Neville, who was once herself an environmental campaigner for WWF, told Eco-Business.

“They recognised that there needed to be a way back for those suppliers,” she said.

Second, the nature advocacy group’s approach is “based on dialogue – not just criticism and campaigning,” Neville said. “That has allowed us to achieve better outcomes, because a genuine collaboration was developed.”

We try to appeal to company executives’ better angels. When that doesn’t work, we are ready to go to the mattresses.

Glenn Hurowitz, founder and CEO, Mighty Earth

Mighty Earth was founded by Glenn Hurowitz in 2016 to protect tropical forests, oceans and the climate, first taking on Korean-Indonesian palm oil firm Korindo, which had been found to clearing vast swathes of jungle in Papua.

The Yale University political science graduate saw the need for a nimble, entrepreneurial advocacy group that “moves at the speed of the corporations that are destroying nature” when he founded the NGO less than a decade ago.

“The companies that we are taking on are much, much bigger, and have way more resources than we do. But sometimes they are slow – and they feel conflicted internally about their actions,” shared Hurowitz in a recent interview with Eco-Business when he was in Singapore.

Philanthropically funded mainly by Western donors, Mighty Earth is a lot smaller than the likes of WWF, Greenpeace and The Nature Conservancy, with 33 staff in offices in Japan, United Kingdom, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Brazil, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. The conservation group does not have offices everywhere, for instance in Indonesia, arguably Southeast Asia’s most important country for biodiverse tropical landscapes, and where it has fought hard for change.

“We don’t want to have an official presence in places that would require us to change our model – which we believe is very effective at influencing companies and governments, even in places that lack robust democratic freedoms,” said Hurowitz.

Where it cannot set up an office, Mighty Earth works with local NGOs and environmental groups to further its cause, such as Satya Bumi, a rare new NGO that launched in Indonesia last year, to hold local firms to account for their no-deforestation commitments.

Over the past few years, Mighty has played a hand in persuading French supermarket Carrefour to stop buying meat from slaughterhouses owned by meat company JBS linked to deforestation, Japanese investment firm Sumitomo Corporation to pull out of overseas coal projects, and Singapore-based agribusiness Olam to stop clearing forests in Gabon.

Mighty Earth is “obsessively focused” on impact, drawing lessons from social movement history, the business world and classical military strategy “to move fast and jump on opportunities when they arise,” Hurowitz said.

Anyone who joins Mighty’s team must first read No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention by the movie streaming service’s founder Reed Hastings.

“The book is about building a culture of freedom and responsibility – and how that drives effectiveness. It’s a system they instituted that embodies the principles that we want to build at Mighty Earth,” Hurowitz shared.

He believes he is in his role to “provide context rather than direction” to his staff, who have the freedom to drive their own strategies.

Hurowitz deploys the “informed captain model”, pioneered by Netflix, which encourages people to listen to their colleagues’ views and make their own judgement call on the right way to do things. This avoids decision-making by committee, which would slow the organisation down and diffuse responsibility, so the theory goes.

“It’s not a good model if you are building airplanes or running a hospital. But in our world, the cost of moving slowly is greater than the cost of making an error and correcting it,” said Hurowitz.

In how it pushes companies to change, the NGO borrows from the strategic approach of French military commander Napoléon Bonaparte, who famously won 90 per cent of the battles he fought, even against much larger enemies, by knowing when and where to concentrate the force of his armies.

“We are in a target-rich environment. It’s easy to do everything at once. But we try to focus on one thing at once,” added Hurowitz. “We are helped by the fact that large companies and investors are increasingly responsive to concerns about the environment.”

One of Hurowitz’s biggest frustrations, though, is how to get bigger. “We’ve got an effective model that gets results. But it’s hard to get the financial resources to scale,” he explained. “We should be 10 or 20 times as big. We’re a lean team. And when you are tackling on a trillion dollar industry, you need resources.”

More resources, which are currently concentrated among American and European donors, could come from Asia, said Hurowitz. “When it comes to environmental protection, I don’t think wealthy Asian actors are playing as big a role as their economic importance suggests they should.”

In this interview with Eco-Business, Hurowitz talks about how to push the most stubborn of companies to change, when to attack companies and when to celebrate success, and why atoning for past damage is the new sustainability frontier for climate-risk companies.

“

Protecting nature and acting on climate change is entirely compatible with the prosperity and growth of companies. It just requires imagination.

How do you influence companies that show no willingness to change?

We try to appeal to every company executive’s better angels. When that doesn’t work, we are ready to go to the mattresses [a reference popularised by the classic Italian-American mafia film The Godfather, which means to enter into a lengthy battle].

But we always go to companies with concrete solutions. When it comes to tackling deforestation, we talk about the fact that there are 125 million hectares of degraded lands across the tropics, where agriculture can be expanded without sacrificing native ecosystems.

Protecting nature and acting on climate change is entirely compatible with the prosperity and growth of companies in agriculture and industry. It just requires a bit of imagination from companies and the understanding that human survival requires that we do things differently.

In Asia, the companies that are continuing to cause problems are the worst of the worst – any company that continues to deforest for palm oil, pulp and paper or rubber, after 90 per cent of the industry has stopped deforesting, has really deep problems. They are the dregs of the industry – some of these companies have criminal connections.

When we take on the companies that refuse our polite entreaties to do the right thing, we’re not always sure we’re going to win. But we usually are able to find the financial, commercial or public levers to influence them. We are able to go faster than some NGOs have historically, because we are able to maintain dialogue. We are always going back to them to propose solutions.

Tell us about your current campaign engaging JBS Foods, the world’s biggest meat company.

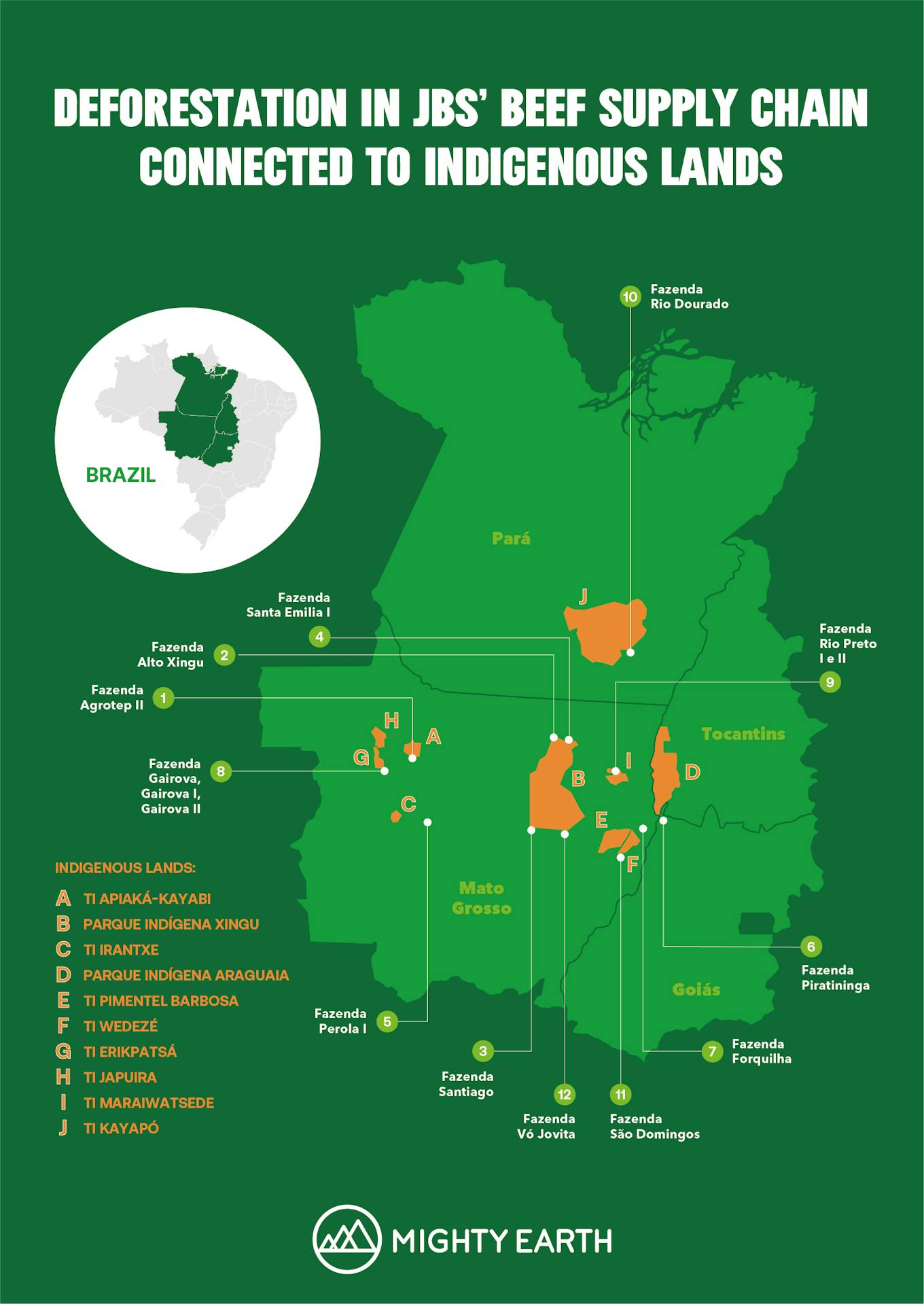

Data highlighting how meat company JBS is harming Indigenous lands in Brazil. Image: Mighty Earth

JBS is the world’s largest corporate driver of deforestation and the largest climate polluter by far – the company has a climate footprint as large as Spain’s. We are very frustrated by their failure to address these issues. And yet we have continued to talk to them to propose solutions, even as we aggressively campaign to pressure them to change. As a result of that, we have been able to persuade them to make some important changes to conserve the Amazon, which they announced in Sharm el Sheikh [at the COP27 climate talks] last year.

There are still huge gaps [in JBS’s climate policy]. They are not protecting ecosystems outside of the Brazilian Amazon, like the Cerrado [a vast region of tropical savanna in eastern Brazil], which if anything is under greater threat [from deforestation] than the Amazon. And they have not announced a full plan to address their methane emissions, which are three times as large as the next three companies [in the meat sector] combined.

But they have also just announced they are starting construction on the world’s largest cultivated meat facility in Spain. Alternative protein is probably less than 1 per cent of their operations, but we need to see that kind of investment to scale a fundamental solution. So, they have taken some positive actions. They are desperate to show improvement – and so we’re going to keep pushing them to bring about more profound change.

The problem with meat companies is that they are stubborn and conservative. But over the last year and a half, for the first time, we’ve seen supermarkets and banks drop meat companies because of deforestation links.

We would not have been as successful if we just told companies how they can work better – we need to show it to them. We do that by working with other organisations that do a great job on the implementation side.

When is it best for an NGO to attack a company, and when is it best to celebrate improvement?

Our lodestar is to tell the truth about what companies are committing to and what they are doing. If a company makes a good commitment and demonstrates sincerity, for instance by bringing in a credible implementation partner, we will celebrate that – even it if it doesn’t address all of the issues that we believe are important. I celebrate the fact that JBS is building the largest cultivated meat facility in the world. But it doesn’t mean I’m going to stop pummeling them for their rampant deforestation and climate pollution.

Our candour has allowed us to remain trusted, even by companies that we are whacking over the head. It’s pretty rare that we get serious pushback about the claims that we make about a company. We always share the findings of our investigations with the companies before we publish them, and in the time we give them to look through the report, companies will often make changes to show that they are taking these issues seriously.

“

The solution for decarbonising energy is for fossil fuel companies to go out of business…Their attitude is: We’re going to ride this train until it kills us.

Mighty Earth campaigned against British supermarket chain Tesco, which had been buying animals reared on soy animal feed grown in an illegally deforested part of the Amazon. Image: Mighty Earth

We recently published a report about [United States-based agribusiness] Cargill, which had been buying soy from a supplier that was engaged in illegal deforestation and land burning in the Amazon rainforest. That soy was being sent to the UK as animal feed, and fed to chickens and pigs that were sold on the shelves of Tesco [the UK’s biggest supermarket chain]. We showed the report to Tesco, and they immediately pressured Cargill to drop the rogue supplier.

What are the biggest problems that worry you the most right now in Asia?

There has been a huge shift in the drivers of deforestation and destruction of nature in Asia. And we need to recognise that shift – or we are not going to be able to make strategies succeed in the future. We’ve seen a 90 per cent-plus reduction of deforestation in the palm oil, pulp and paper and rubber sectors. That’s a gigatonne-scale [carbon] victory that has saved millions of hectares of forest. It’s something to be really proud of.

On the other hand, these companies have done very little to conserve or restore the damage done over decades of utter rapacity. The palm oil industry has destroyed more than 30,000 square miles [the equivalent land area of the United Arab Emarites] of rainforest. None of these commodity agriculture industries have made a serious effort in atoning for that damage. That’s a huge mistake.

They still have a toxic reputation because of that legacy of destruction. It’s a much better reputation than they would have if they were still bulldozing forests. But these big commodity agriculture companies are sitting on billions of dollars. I don’t think it’s too much to ask them to repay the debt to nature that they owe for their spectacular wealth.

But will they ever pay for the damage they have done to nature? A recent report found that fossil fuels companies should pay trillions in reparations for climate damage, but can you ever see that happening?

The solution for decarbonising energy, to a great extent, is for fossil fuel companies to go out of business. Unless these big oil companies are willing to actually become clean energy companies, there’s not a future for them. There are few oil companies that have actually made any meaningful steps towards decarbonisation. Their attitude is: We’re gonna ride this train until it kills us.

Agriculture companies are a bit different. What we are asking for is not that these companies cease to exist, but rather that they operate sustainably. There’s not really a way to operate a fossil fuel company sustainably. Agriculture companies can actually make a positive contribution – but it does require investment.

But we are talking about low-hanging fruit here. Palm oil companies have 1 million hectares of obligations under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to restore forest what has been destroyed just since 2016. But few have even started. The pulp and paper industry has committed to restoring 1 million hectares, but there hasn’t been much progress there either.

Hurowitz speaking at a Global Platform for Natural Sustainable Rubber event in Singapore in June. Image: Mighty Earth

What new issues are you working on?

Rewilding. We are starting to work on bringing back wildlife to areas where it’s been exterminated. We’ve started work on this in North America – but there is a lot of potential for rewilding in Asia as well.

For instance, the Batang Toru Ecosystem in North Sumatra [an area of 150,000 ha, which is home to the Tapanuli population of orangutans, which were identified as the third species orangutans in 2017]. These orangutans are the most endangered great ape species in the world, which live on 2 per cent of their historic habitat.

There is a lot of land around the Batang Toru Ecosystem that could be restored, where we could create an area to grow this population [there are only an estimated 800 individuals remaining]. The Tapanuli orangutan is the ancestral species of the other two types of orangutans, in Sumatra and Borneo, and is the southernmost naturally occurring viable population of orangutans in Sumatra.

An interesting new strategy, rather than exposing companies for wrongdoing, showing them how they can atone for the damage their done?

Exactly. I wish more of companies would embrace conservation and rewilding as an opportunity to be seen as doing something positive.

But don’t you think these companies could then be accused of as greenwashing, if they start promoting rewilding efforts while selling a deforestation-risk products?

More than half of our work is monitoring and driving implementation of existing commitments, rather than securing new ones. Our campaigns that push for a new policy, understandably, get the most attention. But we are not interested in fake commitments. So we do satellite monitoring across the palm oil, soy, cattle and cocoa industries, to make sure that companies are implementing [on their commitments]. We file alerts with the largest agribusinesses linked to deforestation every month. We are not going to let any company get away with greenwashing.

For instance, Cargill committed in 2014 to end deforestation across all of its agricultural supply chains by 2020. They utterly failed to live up to it. When we realised that they were going backwards, we did not hesitate to tell their customers, financiers and the public about their failure. I don’t think that companies believe they can successfully fool us – or the public.

I met with the CEO of a major agribusiness company last week. He said his company had very little deforestation exposure and he was nervous about making a zero-deforestation commitment – because he’s not entirely sure of how to get there. But I said there are so many companies have had that experience – and are succeeding.

But he also said, you never know all the solutions, or you never now have a perfect understanding of what the future holds. But if you don’t have a clear [no deforestation] commitment, it’s very hard to organise workers and stakeholders around an ambition. Success and conservation requires a little bit of courage.

I don’t think anybody would have thought that the palm oil, paper and rubber industries would have succeeded in reducing deforestattion. But they instituted strong supply chain requirements and enforced them.

In contrast, in the cocoa sector, companies have not really enforced [no-deforestation] requirements – they are continuing to buy cocoa with a fairly laissez-faire attitude. One of the differences is that the cocoa industry did not include civil society in their monitoring and transparency systems. They tried to hold it close and do it themselves, but they utterly failed.

NGOs keep companies honest. We set up a Rapid Response forest monitoring project. We monitor 21 million hectares of forest regularly in Southeast Asia, and we file alerts based on that with the top 32 palm oil companies. A lot of those companies have the data that we have. When we share alerts with them, that gives them political cover to enforce their policies internally. They can say to their suppliers: It’s not us, it’s Mighty Earth forcing us to do it.

Where are the big gaps in tackling deforestation now in Asia?

We’ve seen dramatic progress in reducing deforestation from the private sector. The main problem now is with state-backed development projects and small number of cronies that operates around the government.

For example, the Food Estates project in Indonesia. It probably won’t produce much food, but it is a massive threat to forests. There are also infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia, such as dams and roads, that will have an outsized impact on wildlife. And most of those projects – when you dig down – don’t have a great economic rationale behind them.

For example, the Batang Toru hydropower dam project [which threatens to fragment a large area of the Tapanuli orangutan habitat]. There is no need to pump more electricity into that region – there’s an oversupply. So why is it happening? I think it’s a mechanism to funnel Chinese dollars [the dam is funded by a China-based company] into the pockets of well-connected companies. It’s not the large, international private sector companies are driving deforestation right now. It’s state-backed, politically-connected ventures.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.