While the global market for green bonds reached a record of more than US$155 billion last year, there are still only a few banks in developing countries in Southeast Asia that have issued such bonds, which fund projects that have environmental benefits.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The main reason for Southeast Asia’s luke warm reception to green bonds is because foreign investors are “not familiar” with the banks in the region, no matter how high their credit risk ratings are, said Ephyro Luis B. Amatong, commissioner of the Philippines Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Image: Eco-Business

Among the developing countries in the region only Indonesia and the Philippines have issued green bonds, while Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos have nascent or no bond market just yet.

Last month, Thailand issued a US$100 million sustainability bond—which differentiates itself from a green bond by financing projects that not only bring environmental but social-economic benefits as well.

Amatong said that lenders like International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private development arm of the World Bank Group, have to act as “anchor investors” for these banks to spur the growth of green bond markets in developing countries.

“What we would appreciate is for IFC to introduce these banks to a wider investor base so that when investors see that the quality of the issued bond is investment grade, they might buy it at a premium,” Amatong told Eco-Business on the sidelines of a corporate governance forum in Pasay City, Philippines in October.

Amatong cited the fund IFC set up with Amundi, Europe’s biggest listed asset manager, as an example of how the agency can further increase the number of investors for banks in developing countries that issue green bonds. The fund, which closed in March, raised US$1.42 billion, of which IFC contributed US$256 million, and is expected to encourage more financial institutions in emerging markets to issue green bonds.

The inclusion of IFC as a major investor in a bank’s green bond serves as a “signaling mechanism” to foreign investors that the bank is credible, added Amatong.

IFC has the international expertise that will ensure that the investment goes to climate-financed projects, as it co-developed the global framework for issuing green as well as social and sustainable bonds, he said.

“

What we would appreciate is for IFC to introduce these banks to a wider investor base so that when investors see the quality of the issued bond is investment grade, they might buy it at a premium.

Ephyro Luis B. Amatong, commissioner, Philippines Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

Aileen Ruiz Zarate, a senior investment officer of IFC’s financial institutions group, clarified that it is also IFC’s goal to help banks widen their investor base in funding green projects, but it is still the issuing bank’s decision if they want to do so.

The issuance of US$150 million in green bonds by the Philippines’ seventh largest bank Chinabank last October was made directly to IFC, rather than offered to the public. Before that, IFC also invested in the first green bond issued by the country’s largest bank, BDO Unibank Inc., in December last year.

“BDO and Chinabank’s bond issuances were private placements. It was their choice to have it that way for their first [green bond] issuances,” Zarate told Eco-Business. “If we were to do the next one with the same banks, we would rather have it made public.”

The emerging green opportunity

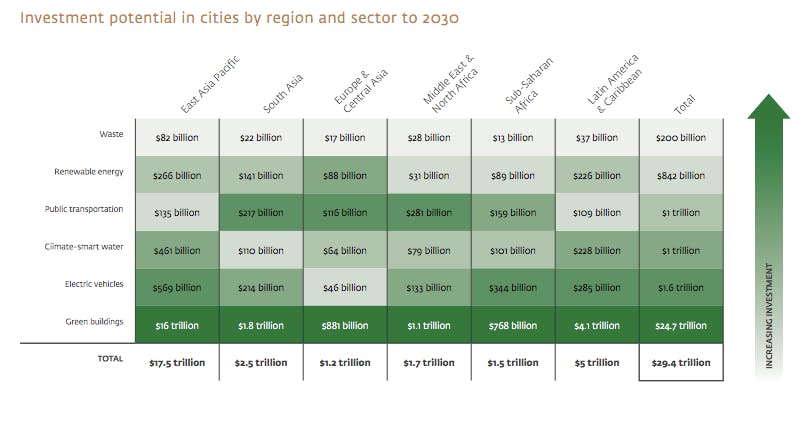

Although the uptake of green bonds has started slowly in developing countries in this part of Asia, East Asian cities could attract up to US$17.5 trillion in climate-related investments over the next decade, IFC said in a report on Thursday.

The study said that green bonds could be used to narrow the financing gap for climate-smart projects like green buildings, electric vehicles, and climate-smart water, which is water resources and infrastructure that is resilient to the stresses of climate change.

The report stated: “Debt financing instruments such as green bonds have great potential to drive climate-smart investment by allowing cities to acquire long-term debt at stable prices.”

Source: International Finance Corporation

In a table detailing the region’s green investment potential, the report showed that the bulk of the opportunity will be in green buildings with US$16 trillion in investment. Southeast Asia’s second largest’s city, Jakarta, has US$16 billion of investment potential in green buildings, which is expected to save energy, costs and reduce emmissions.

Indonesia’s capital aims to build at least 1,000 low-cost residential towers by 2020 to house people who have been relocated from informal settlements in the low-lying, flood-prone riverbank area, according to the report.

The Allianz Tower in the central business district of Jakarta is one of the 260 green buildings in the capital as of 2016. Image: Galawana via IFPRI Flickr

IFC’s study also pointed to the priority given to water by cities in the region for communities and new businesses that rely on the resource for their operations, as reflected by the US$461 billion opportunity in climate-smart water.

The report found that climate-smart water and wastewater management projects had the biggest investment potential for Jakarta after green buildings. Heavily criticised for not providing residents with access to clean water, the government requires an estimated US$3 billion investment to secure piped water instead of extracting water from the ground.

The report also detailed a US$569 billion potential for investment in electric vehicles in the region. IFC estimated that Jakarta will have an investment opportunity of US$660 million in public transport and almost US$7 billion in electric vehicles by 2030 for the city to achieve its plans to create a sustainable transport system.