Stanzin Dolma is a woman who lives in the remote village of Shade, in the Zanskar valley of Indian Himalayas. Her village is located at a trek distance of five days from the nearest motorable road.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Dolma has a house in this centuries old village and is living with her husband and three children. She tends to her farms during the daytime and comes back to her house in the evening.

Once back, she lights up the kerosene lamps to provide illumination in the darkness of her house. Her family received a battery and two CFL lamps many years ago from the government; these have stopped working so kerosene lamps are their only hope for light.

According to the World Bank, over 1.1 billion people have no access to electricity, and a billion more only have intermittent access. These people rely on costly, outdated technologies that are harmful to their health, and hinder their opportunities for social and economic advancement.

The people resort to kerosene lamps, candles, and smoky, inefficient cookstoves, which cause more health damage and environmental damage. The household pay most of the money as proportion of their household income for inadequate, dangerous, and unhealthy energy sources that kill many women and children prematurely.

How does one reach to Dolma in the first place, and once you reach her village, how do you provide them access to energy given the geographic constraints?

There is a push for universal energy access by governments all over the world, however the barriers to reach universal access are socioeconomic, geographic and demographic.

The challenge of reaching remote populations in rural areas makes capital-intensive electrification even more costly. Setting up of grid infrastructure involves huge investments during construction phase.

These initial investments and the operating expense need to be recovered from the end users through a monthly tariff.

Here is where things become difficult, since the high cost is being spread among rural population and the population is spread out, which results in a very high per household monthly tariff — more than what we end up paying in cities. The poor people end up paying more than the rich people for getting electricity.

This is one of the major reasons that providing access to villages does not immediately result in the acceptance of electricity in each and every household.

A family uses kerosene lamp to light their home. Image: Jaideep Bansal

So what do you do? How can one reach out to the several women like Dolma who don’t have access to electricity and improve their living conditions?

“

It is imperative for us to work on the three areas of energy access, energy efficiency and energy economy to achieve universal energy access, and achieve it a faster pace than what it is today.

The lack of electricity is a deterrent to income generating opportunities and blocks the outcomes on any investments done on education, health and women improvement.

Households end up paying almost their entire month salary to buy kerosene for purpose of lighting up the household. To supply electricity to a villager, living in poverty and hardly managing to eat three meals a day, the cost has to be optimised.

This can be answered in three parts — energy access, energy efficinecy, and the energy economy.

Energy access

One part of the answer lies in using decentralised power generation and mini grids to service the offgrid communities.

Off-grid electrification, largely driven by local renewable resources has grown significantly over the past decade and is used to power new connections in rural areas. The traditional grid solution of utilities is now being complemented by off-grid solutions consisting of mini-grids and standalone home lighting systems.

A village electrified using solar micro-grids. Image: Jaideep Bansal

These innovative solutions are eliminating the need of a capital intensive infrastructure thereby allowing a low monthly tariff per household.

There has been an immediate acceptance of mini grid and home lighting solutions in every community across the globe due to the low cost.

Villagers have stopped buying kerosene and use only a part of the saved money to pay the monthly tariff. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates there is an $18 billion market to serve these bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers that represents an untapped market opportunity for the private sector.

Energy efficiency

The second part of the answer lies in energy efficiency. If 1.1 billion people across the globe need to be provided access to electricity, it makes perfect sense to start these communities on energy efficient technologies and devices.

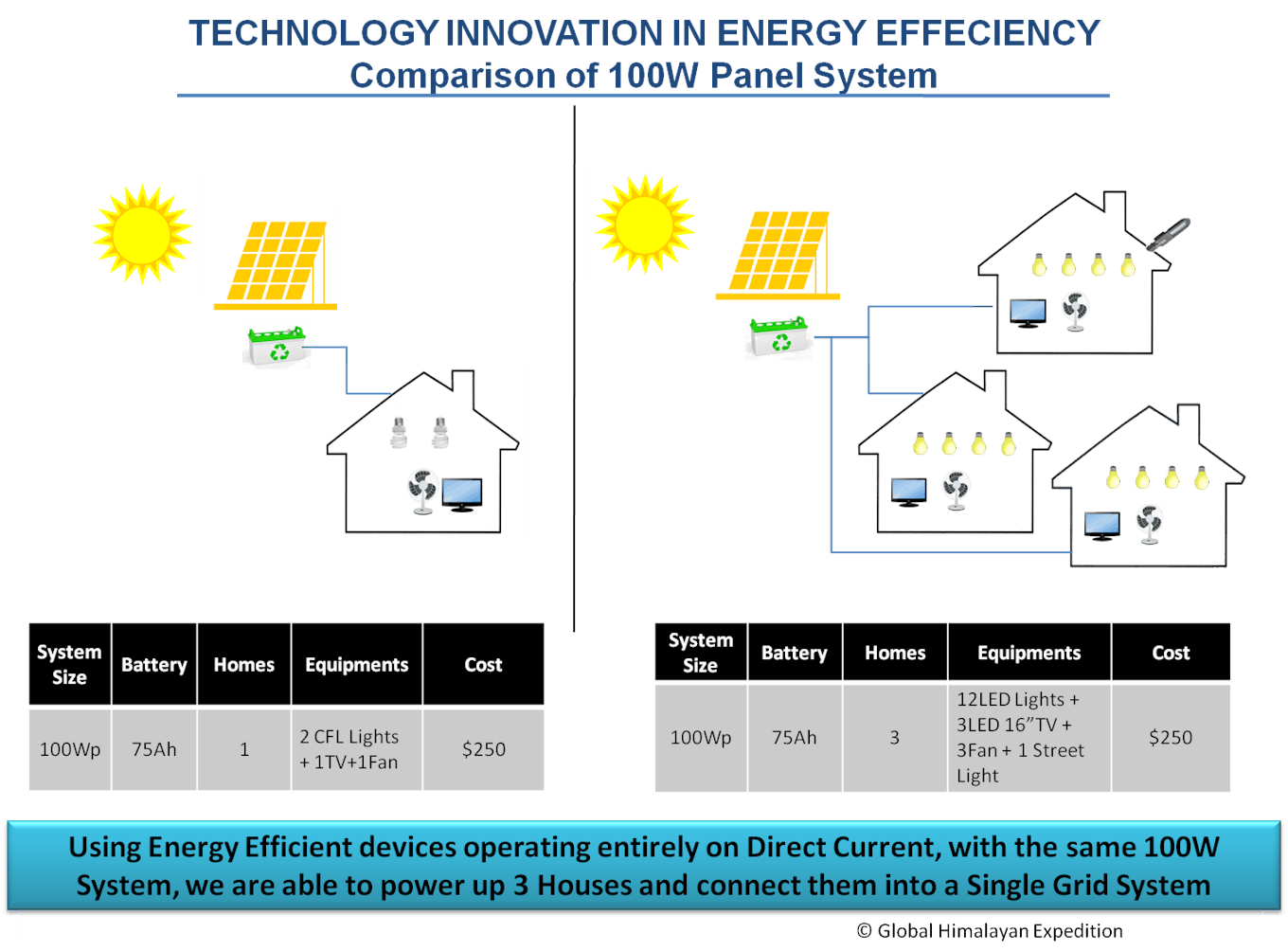

New initiatives to integrate energy efficiency mechanisms with energy access are also now being promoted in the developing countries. Conventional electricity is AC (Alternating Current) in nature, however the electricity generated at source is DC (Direct Current) in nature.

The conversion involves a 30 per cent loss, which can be eliminated if the community is powered up using DC electricity. And this is possible for rural communities that stay together and are not spread out.

DC Grids are now coming up as a practical answer to fulfil the energy needs of cities also. A growing number of devices in our homes run on DC- our mobiles, laptops, electric cars, LED Lights.

Data centres increasingly use local DC micro grids for efficiency and cost savings. Using DC Grids offers the potential for home owners to power up their houses with Renewable energy and feedback energy to the grid.

Energy economy

Universal energy access is the most discussed theme at any national and international conference. There is a lot of funding put in by international organizations and corporate partners to accomplish the goal of energy access. However, the missing link is the development of a local energy economy.

Let us go back to Dolma to understand more what an energy economy means. Getting funds from outside India in order to buy a solar panel and an LED Light from outside India is not really contributing to the economic growth of Dolma directly. She becomes an end user of a free technology donated to her.

But what if you could train Dolma to assemble her own LED Lights? What if you could get Dolma to buy the LED Lights from a local store, LED Lights that are manufactured in her own region by women like her.

Global Himalayan Expedition electrified a village in Himalayas this year, and gave villagers the provision to add television to the home grid on the condition that they buy the television. Out of 10 households, 9 bought the television, resulting in income generation for the local entrepreneurs.

Energy access can be a big driver to promote entrepreneurship and skills development in the rural areas by engaging the communities to manufacture goods locally using the funding. This will result in developing an economy working to fulfil the energy needs of the area.

A woman runs a home-stay in her village catering to 1,000 tourists in a year.

Parallel economies that develop are handicrafts produced from the extra working hours that villagers get from the energy access, and the promotion of tourism to these rural communities provide tourists an experience of local culture and tradition with good facilities and charging points for their iphones.

The homestays, as they are called in the villages, give tourists a chance to stay with the locals and experience their culture and tradition while allowing the villagers to earn income from the tourists. All this results in the creation of a livelihood where in the starting point was the access to energy.

It is imperative for us to work on the three areas of energy access, energy efficiency and energy economy to achieve universal energy access, and achieve it a faster pace than what it is today.

Only when the three areas will be linked, will there by a successful transition of the world from energy poverty to energy sufficiency.

Jaideep Bansal is the Energy Access Leader for the Global Himalayan Expedition, and is also a global shaper from the World Economic Forum. He and his team has been involved in the setup of DC based Solar Micro Grids for the off grid remote Himalayan Villages, electrifying 25 villages and impacting the lives of over 15,000 people, and plans to electrify 40 more villages in 2017.