One of the few things the world can agree on today is that we are clearly in the midst of an unprecedented period of transformation. We’ve had a global pandemic that has been the worst since the Spanish Flu, a war in Europe, rising geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions and an escalating cost of living crisis – all amid an accelerating climate crisis.

Major forces are driving a range of systemic changes across our global economy, and nowhere is this more evident than in the energy transition underway.

This issue was sharply in the spotlight amid competing challenges at the G20 summit hosted by the Indonesia for the first time in November, where world leaders, the business community, and to a lesser extent civic society met in Bali to shape the global agenda for the coming years.

Happening around the same time was the annual climate change negotiations known as COP27 taking place in Egypt’s Sharm el Sheikh where there was much gnashing of teeth between developed and developing nations on the issue of climate finance and loss and damage.

At the centre of this tension is the fact that the global community is faced with the challenge of requiring an incredibly large scale of change in a very narrow window of time — it is a problem that requires the coooperation of every country, yet their capacity to execute this varies wildly from one nation to the other.

This decade, termed the “decade of action” by the United Nations, is when sharp reductions in emissions have to be made to ensure a stable climate, while at the same time, addressing other priority issues such as the post-pandemic economic recovery, poverty and energy security – particularly for developing nations.

In 2021, the global rate of decarbonisation (measured as the reduction in carbon intensity per dollar of GDP) was 0.5 per cent — this needs to be at a much higher 15.9 per cent to limit warming to 1.5 degree Celsuis, according to PwC’s latest Net Zero Economy Index.

The taskforce on energy, sustainability and climate of the B20 – the official G20 dialogue forum for the global business community – has made collaboration between developed and developing countries a central theme of the call to action. “Gotong royong”, as it is said in Bahasa. But how will this work in practice? How can we unlock blended finance – both public and private capital – into sustainability-driven infrastructure projects for the energy transition?

The B20 Summit on 13 to 14 November in Bali, organised by the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (KADIN). Image: B20 Indonesia

This was discussed in detail on a B20 panel that I moderated on investing in green ventures for sustainable growth organised by the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, also known as KADIN. Here are four takeaways.

1. The just energy transition will require the phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies and funding from developed economies

It has been a topic of much debate, but the reform of fossil fuel subsidies is required and everyone from policymakers to voters should demand this urgently. In 2019, global fossil fuel subsidies to consumers added up to US$320 billion, a significantly higher amount than the US$280 billion global spending in renewable energy capacity investments and US$250 billion global spending in energy efficiency enhancements, according to the think tank International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

The redirection of public funding, along with carbon tax revenues, should go towards the deployment and adoption of sustainable energy sources and technologies, and targeted application of consumption subsidies will be critical to addressing energy poverty.

Notably, the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) was launched at the G20 by United States President Joe Biden and Indonesian President Widodo among others. It is a US$20 billion long-term partnership designed to fund and create an ambitious and just power sector transition in coal-reliant Indonesia.

This JETP will include a target, for the first time, a 2030 peaking date for Indonesia’s power sector emissions and help reduce cumulative greenhouse gas emissions by more than 300 megatonnes through 2030 and a reduction of above 2 gigatonnes through 2060 from Indonesia’s current trajectory.

Its architects say the JETP will focus not only on delivering strong emissions reductions, but also drive sustainable development and economic growth, while protecting the livelihoods of communities and workers in affected sectors. It is still early days, but the JETP is an encouraging example of the collaboration we need.

2. Regulation and finance must provide an enabling environment

The reality is that high capital expenditure investments require low financing costs but, counter-intuitively, capital is more expensive for developing countries than developed ones.

Michele Crisostomo, chairman of Italian energy firm Enel Group and a member of the B20 Taskforce on finance and infrastructure, emphasised on one side the need to create more financial products that will fund infrastructure gaps in the energy transition, but on the other side the support needed to create a pipeline of investment-ready projects.

Blended finance has emerged as a key mechanism to unlock large capital flows from private sources but investors’ perception of high risk related to developing nations must be addressed first.

“

It is clear that the energy transition is a complex undertaking that requires unprecedented political will, private sector support and public buy-in.

Regulation is crucial to enabling this and developing nation policymakers must prioritise the implementation of sound economic and financial policies to create a stable economic environment so local financial institutions can facilitate the required financing in a safe and clearly regulated environment.

There is also an urgent need to harmonise sustainable finance taxonomies across the globe to ensure a level playing field and to limit reputational risk.

Current numbers indicate the global financial system is far behind where it needs to be. Finding a balance in the risk approach – for example, whether climate risk penalises or advantages a project for investment – will be the key challenge. “Without this, I don’t think the transition will go at the right speed”, stressed Crisostomo.

Another key point made was support for climate innovation and viewing the climate crisis as an opportunity. Despite recent momentum, a technological gap exists for the world to achieve net zero.

According to a recent BCG report, 20 to 30 per cent of these technologies are not yet available, and the other 70 to 80 per cent are in early adoption and a much quicker pace is required.

The participation of MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) in adopting cleaner technologies is also crucial to this transition and requires support in plugging financing gaps, capacity building and simplifying permitting and business application processes.

3. Don’t underestimate the manufacturing muscle we need

Insufficient attention is currently being paid to the scale of manufacturing capacity and capability required in transforming our energy systems.

David Griffin, founder and CEO of Sun Cable, puts it starkly: “Every component is in short supply. Everything. The scale of the energy transition is still very poorly understood. It is far bigger than anything in human history: We need more manufacturing capacity, and we need it close to where the projects are rolling out.”

Sun Cable is an ambitious Australia-Asia power link project featuring the world’s largest 18 gigawatt (GW) solar farm and 40 GW battery storage facility with a 5,000 km transmission from Australia’s northern territory to Darwin and then passing through Indonesia territory to Singapore, where it could deliver 15 per cent of the city-state’s energy demand.

The project is using technologies that already exist, but which have “never been put together at this scale and in this particular configuration. So, our biggest challenge is finding a way to optimise the design,” added Griffin.

Sun Cable is relying on artificial intelligence to optimise the design, improve efficiency and drive down costs. The company announced a collaboration on inter-island grid connectivity policy and technical programme development with the Indonesian government last month, which it says will “unlock an estimated $115 billion in green industry economic potential in the archipelago over the next decade”.

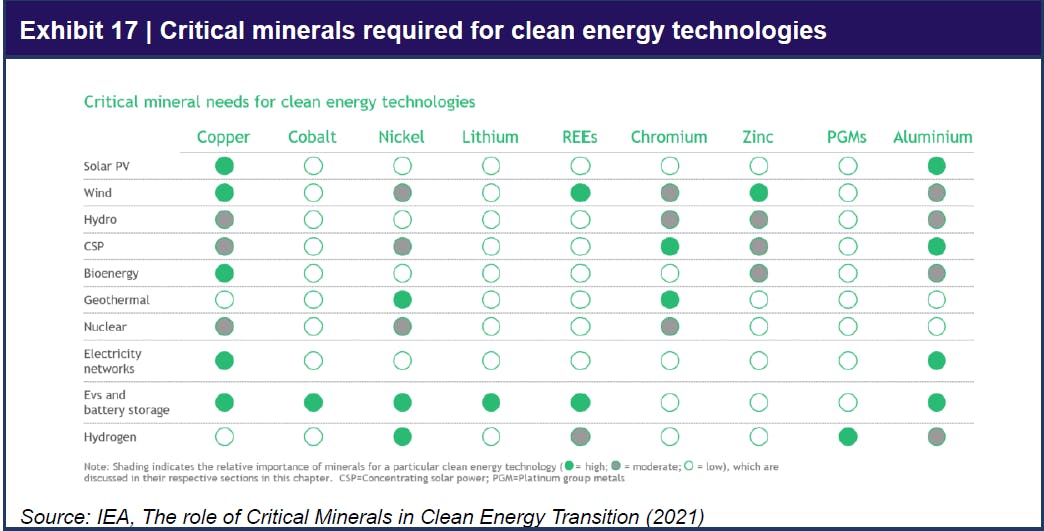

The other less talked about dimension is the need to ensure better practices for the mining of these essential minerals such as nickel, cobalt, and lithium needed for the energy transition. The B20 taskforce recommended that G20 countries set policies and guidelines such as disclosures and reporting standards, and multi-lateral funding for sustainably-managed mining projects, upskilling programmes, and global cooperation.

4. The Russia Ukraine war should speed up the energy transition, not slow it down

Finally, a lot has been said about how the Russia invasion of Ukraine has thrown a curveball to energy markets by essentially removing 155 billion cubic metres of natural gas from Europe and stalling the energy transition by forcing a pivot to polluting coal.

Datuk Tengku Muhammad Taufik, chief executive of Petronas, Malaysia’s energy giant, noted: “We’ve had 40 per cent [of supply] out of the equation immediately… and the imbalance is not something you can easily correct.”

A just and responsible transition, he said, means “taking account of stakeholders everywhere in the world with their own idiosyncrasies, different starting points and different cost of living challenges.”

Radosław Domagalski-Łabędzki, CEO of Polish energy manufacturing giant Rafako, pointed out that the war should instead accelerate the energy transition so it is “independent from external sources”. He cited the recent explosion of the gas pipeline in the Baltic Sea as unprecedented attacks on critical infrastructure that need to be factored into investment decision-making on energy projects.

He also emphasised the need to manage the transition period, saying that coal units should be retrofitted with more efficient, emissions-reducing technology instead of shuttered, using them as a base only in peak periods to support renewables, including hybrid renewable energy set ups that combine wind and sun energy together with energy storage systems on a large scale.

The war has also resulted in other cleaner energy sources such as small, modular nuclear reactors re-emerging from the grave. But a high degree of regulation and customised financial instruments like guarantees and insurances are required to make it happen, he added.

A new energy revolution

It is clear that the energy transition is a complex undertaking that requires unprecedented political will, private sector support and public buy-in.

But just as the industrial revolution two centuries ago resulted in the extraordinary combination of cheap, abundant energy and raw materials that built our modern economy, it is entirely within our reach to enable a new energy revolution within our lifetimes that will put us on a path of global stability and security.

The key is making the right investment decisions – anyone who manages money should never lose sight of this.