Imagine a country that met the basic needs of its citizens – one where everyone could expect to live a long, healthy, happy and prosperous life. Now imagine that same country was able to do this while using natural resources at a level that would be sustainable even if every other country in the world did the same.

Such a country does not exist. Nowhere in the world even comes close. In fact, if everyone on Earth were to lead a good life within our planet’s sustainability limits, the level of resources used to meet basic needs would have to be reduced by a factor of two to six times.

These are the sobering findings of research that my colleagues and I have carried out, recently published in the journal Nature Sustainability. In our work, we quantified the national resource use associated with meeting basic needs for a large number of countries, and compared this to what is globally sustainable. We analysed the relationships between seven indicators of national environmental pressure (relative to environmental limits) and 11 indicators of social performance (relative to the requirements for a good life) for over 150 countries.

The thresholds we chose to represent a “good life” are far from extravagant – a life satisfaction rating of 6.5 out of 10, living 65 years in good health, the elimination of poverty below the US$1.90 a day line, and so on.

Nevertheless, we found that the universal achievement of these goals could push humanity past multiple environmental limits. CO₂ emissions are the toughest limit to stay within, while fresh water use is the easiest (ignoring issues of local water scarcity). Physical needs such as nutrition and sanitation could likely be met for seven billion people, but more aspirational goals, including secondary education and high life satisfaction, could require a level of resource use that is two to six times the sustainable level.

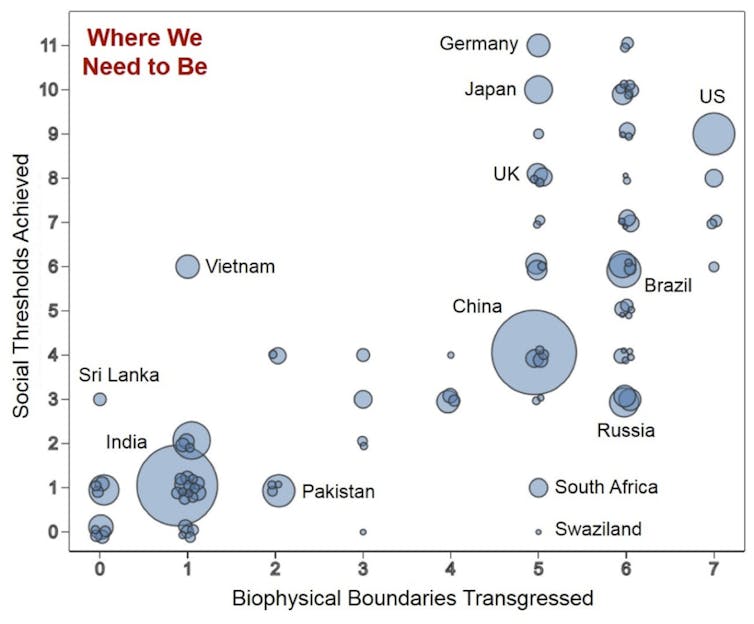

Although wealthy nations like the US and UK satisfy the basic needs of their citizens, they do so at a level of resource use that is far beyond what is globally sustainable. In contrast, countries that are using resources at a sustainable level, such as Sri Lanka, fail to meet the basic needs of their people. Worryingly, the more social thresholds that a country achieves, the more biophysical boundaries it tends to transgress.

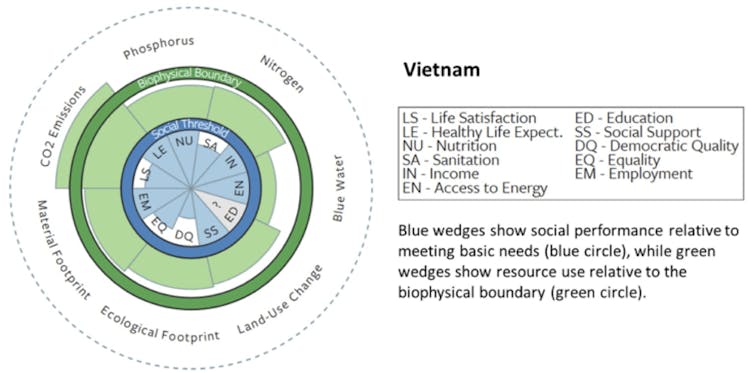

No country currently achieves all 11 social thresholds without also exceeding multiple biophysical boundaries. The closest thing we found to an exception was Vietnam, which achieves six of the 11 social thresholds, while only transgressing one of the seven biophysical boundaries (CO₂ emissions).

To help communicate the scale of the challenge, we have created an interactive website, which shows the environmental and social performance of all countries. It also allows you to change the values that we chose for a “good life”, and see how these values would affect global sustainability.

Time to rethink ‘sustainable development’

Our work builds on previous research led by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, which identified nine “planetary boundaries” that – if persistently exceeded – could lead to catastrophic change. The social indicators are closely linked to the high-level objectives from the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. A framework combining both planetary boundaries and social thresholds was proposed by economist Kate Raworth, and is described in her recent book Doughnut Economics (where the “doughnut” refers to the shape of the country plots, such as the one above for Vietnam).

“

The relationship between resource use and social performance is almost always a curve with diminishing returns. This curve has a “turning point”, after which using even more resources adds almost nothing to human well-being.

Our findings, which show how countries are doing in comparison to Raworth’s framework, present a serious challenge to the “business-as-usual” approach to sustainable development. They suggest that some of the Sustainable Development Goals, such as combating climate change, could be undermined by the pursuit of others, particularly those focused on growth or high levels of human well-being.

Interestingly, the relationship between resource use and social performance is almost always a curve with diminishing returns. This curve has a “turning point”, after which using even more resources adds almost nothing to human well-being. Wealthy nations, including the US and UK, are well past the turning point, which means they could substantially reduce the amount of carbon emitted or materials consumed with no loss of well-being. This would in turn free up ecological space for many poorer countries, where an increase in resource use would contribute much more to a good life.

![]() If all seven billion or more people are to live well within the limits of our planet, then radical changes are required. At the very least, these include dramatically reducing income inequality and switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy as quickly as possible. But, most importantly, wealthy nations such as the US and UK must move beyond the pursuit of economic growth, which is no longer improving people’s lives in these countries, but is pushing humanity ever closer towards environmental disaster.

If all seven billion or more people are to live well within the limits of our planet, then radical changes are required. At the very least, these include dramatically reducing income inequality and switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy as quickly as possible. But, most importantly, wealthy nations such as the US and UK must move beyond the pursuit of economic growth, which is no longer improving people’s lives in these countries, but is pushing humanity ever closer towards environmental disaster.

Daniel O’Neill isLecturer in Ecological Economics at the University of Leeds. This article was originally published on The Conversation.