In the run-up to the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP 28) on climate change, Southeast Asia is in the spotlight not only as a hotspot for climate impacts but also for the urgency to take climate action. Policymakers in the region see the imperative for climate mitigation and adaptation but underscore the inadequacy of climate finance as an impediment. The region, according to one estimate by the Asian Development Bank, requires US$210 billion annually through 2030 for climate infrastructure investment. That would be 12 per cent of the US$1.8 trillion of sustainable infrastructure investment needed annually through 2030 for emerging economies (excluding China), as estimated by an independent panel for the 2023 G-20 meetings.

A significant proportion of the investment needed stems from the cost of transitioning away from carbon-intensive industries, investing in renewable energy, and improving energy efficiency. Additionally, protecting forests and adopting sustainable land use practices are vital for carbon sequestration. Adaptation measures are also needed, including strengthening transportation and energy infrastructure to withstand extreme weather, finding drought-resistant crop varieties, and activating early warning systems for natural disasters.

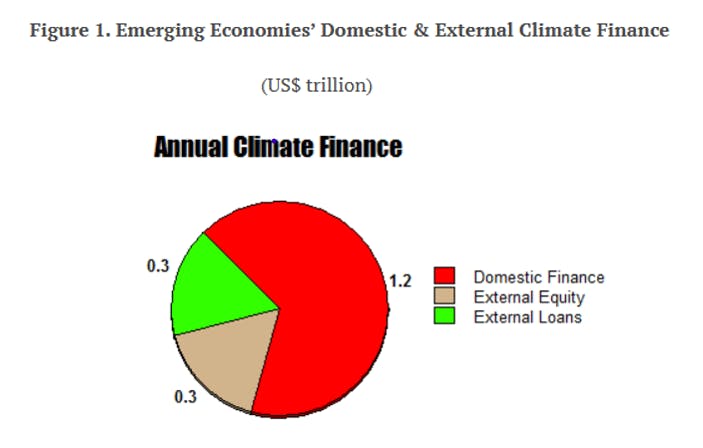

The size of the needed climate investment translates roughly to 4-5 per cent of the GDP of Southeast Asia and emerging economies. An analysis of the US$1.8 trillion suggests that two-thirds of the figure, or US$1.2 trillion, will have to be raised domestically (illustrated in Figure 1). The remaining US$0.6 trillion could come from international sources. About half of the US$0.6 trillion would come from private debt and equity flows and the other half from public sources, mainly multilateral development banks (MDB). Considering that the World Bank Group’s total lending was US$71 billion and the Asian Development Bank’s US$20 billion in 2022, the climate financing gap would appear to be large.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to encourage multiple sources of climate finance from multiple stakeholders using innovative financing mechanisms. The political constraints to opening new avenues away from the monopolistic or oligopolistic hold of state-owned enterprises need to be addressed. It would help to strengthen policy and regulatory frameworks, including price signals, governing climate finance. These signals include financial incentives for green bonds. For example, government-linked and other state-owned enterprises in Indonesia should be able to issue green bonds to supplement green infrastructure projects that are financed by the government budget. MDBscan boost domestic green bond markets in Indonesia and other countries by providing guarantees against the loss of capital.

Steps to raise the profile and credibility of green finance in domestic markets will help. As investment in renewables and other green ventures are typically risk prone, greater transparency in the nature and intensity of those risks will help. For example, accounting for climate impacts in asset valuation can be conducted. For instance, the Philippines or Vietnam — countries with high exposure to extreme weather — would gain from more transparent accounting of the risks. Better communication can also help. To promote a better understanding of green bonds and other index-linked products, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have developed taxonomies that establish a common language for green investment.

The 2023 G20 meetings suggest that US$1.8 trillion of sustainable infrastructure investment is needed annually up to 2030 for emerging economies, excluding China. Two-thirds, or US$1.2 trillion, will have to be raised domestically. Image: Vinod Thomas/ Fulcrum

Carbon markets and trading, underpinned by quantitative restrictions or taxes on carbon, can provide another source of finance for Southeast Asia. By putting a price on carbon, businesses are, in one way or another, motivated to reduce emissions. These mechanisms create economic incentives for emission reductions by allowing the buying and selling of carbon credits. Southeast Asian countries can participate in international carbon markets, generating revenue from emissions reductions achieved through their climate projects.

Given the size of the financing gaps, Southeast Asia should also tap into grassroots financing mechanisms. Community-based initiatives, crowdfunding, and social impact bonds can empower local communities to contribute to climate projects. This bottom-up approach helps climate finance to reach those most vulnerable to climate change. Frank Lysy, a former World Bank economist, notes that in cases where a massive scale of investments took place, be it in cellular mobile services or digital technologies, the viability of the technologies and supportive regulatory frameworks were key, not top-down financing by the public sector. Climate finance is different from those instances, given the vast spillover harm inherent in emissions and the risks of clean technology. Nonetheless, the role of grassroots financing should be capitalised on.

The nature and even the extent of climate finance can also be influenced by giving greater play for nature-based solutions defined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems”. One example of such an initiative is the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. The flyway, one of the world’s great flyways of migratory birds, utilises nature-based solutions that are also climate-friendly. The Philippines is also trying to employ nature-friendly solutions to mitigate flood risks in six river basins.

In line with the agenda for COP 28, Southeast Asia needs to mobilise sizable resources to tackle mitigation and adaptation needs. Even though climate change is a part of these other problems, policymakers are stretched by other urgent priorities and have to tackle multiple issues, such as food insecurity to health care. Given such competing priorities, the urgency of climate action seems to take a backseat in the eyes of the politicians and the public. But given the escalating climate catastrophe and its sizeable financing requirements, it will take a combination of avenues — domestic funding, multilateral support, carbon markets, private sector engagement, and grassroots financing — to bridge the gap.

Vinod Thomas is currently Visiting Senior Fellow at the ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute, and previously Visiting Professor at National University of Singapore. He is a Distinguished Fellow in Development Management at the Asian Institute of Management, Manila, and a member of the advisory panel on climate change at CSEP, New Delhi.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.