On July 22, the Xepian-Xe Nam Noy hydropower dam under construction in Laos’ Attapeu Province collapsed. Flash flooding inundated eight villages, killing at least 29 people and leaving 131 officially reported missing. The final number of casualties could be much higher.

Disaster response activities are ongoing. The deputy secretary of the province claimed that more than 1,100 people were still unaccounted for, as of July 27. Laotian authorities are investigating whether the collapse was caused by heavy rainfall, inadequate construction standards, or a combination of the two.

The dam is part of a larger joint venture between Laotian, Thai and South Korean companies, which are reportedly helping with the rescue and restoration effort. The companies are also sending experts to assess the damage and investigate the cause of the disaster.

This is not the first time that a hydropower project in Southeast Asia has been in the spotlight. It again raises questions about the benefits of such projects for local communities, considering the risks to which local people are exposed.

Not only do large developments interfere with ecosystems, but they often affect local communities even in the absence of catastrophe. This was indeed the case for the Xepian-Xe Nam Noy project, which had already cost many villagers their land and livelihoods before disaster struck.

As much as we tend to focus on the “natural” triggers for disaster—in this case heavy rain—the reality is more nuanced. These incidents are often also the result of flawed development, and as such they are social and political disasters too.

So, was this disaster just a terrible accident? Or is it emblematic of a development agenda that is out of sync with the needs of a healthy environment and local community?

The impacts of hydropower

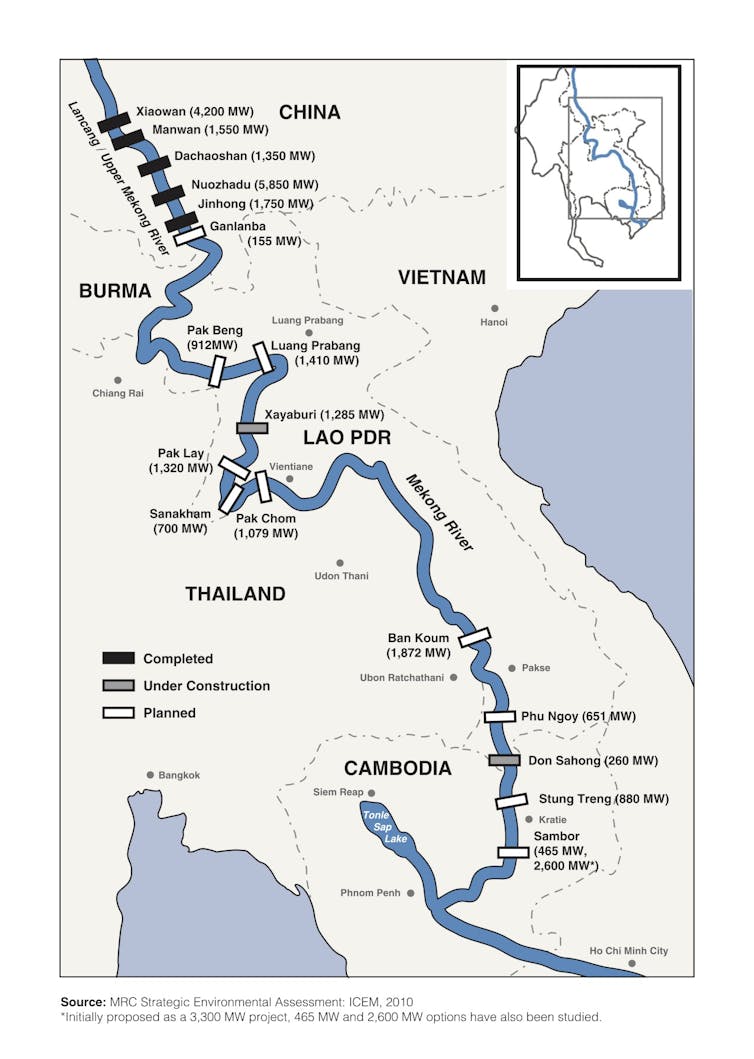

Hydropower projects in Southeast Asia, and particularly in the Mekong catchment, have long exposed vulnerable communities to risk while developers reap the rewards. Millions of people depend on the Mekong river for water, fish, transport and irrigation.

Dam developers promise that their projects will deliver a wide array of benefits: renewable energy, bountiful reservoir fishing, profitable reforestation, harmonised water allocation, and better flood control. But these controversial projects often dramatically change local livelihoods for the worse.

We have seen this before, both in Laos and in its neighbouring countries. The Nam Song Diversion Dam, completed in 1996, affected more than 1,000 Laotian families—first by removing their access to productive agricultural land and causing a severe decline in fish stocks. Since then, deliberate water surges—for electricity generation—have been blamed for three deaths and widespread loss of boats and fishing equipment.

The Nam Theun 2 Hydropower Project boasted rigorous social and environmental safeguards—but these soon became broken promises. This project also followed a disturbing trend relating to hydropower development in Southeast Asia: the dispossession of already marginalised ethnic minorities.

In neighbouring Cambodia, the Kamchay Dam displaced thousands of people, jeopardised their livelihoods, and caused irreparable damage to the environment. The Pak Chom Dam in Thailand similarly put local livelihoods at risk.

So despite providing clean renewable energy, many hydropower projects in Southeast Asia have also deepened inequality and marginalisation.

“

Was this disaster just a terrible accident? Or is it emblematic of a development agenda that is out of sync with the needs of a healthy environment and local community?

People vs profit

This latest disaster should therefore be seen in the context of broader criticism concerning damming the Mekong and its tributaries.

Some analysts have argued that local communities in the Mekong delta are being caught in the middle of a cross-border water grab. Private and state-backed actors from China, Thailand, and Laos profit handsomely from hydropower projects, but critics argue that all too often the negative impacts of dams are ignored.

Local protests against development projects are often suppressed, and governments regularly align with private interests to maximise profit and protect developers from any repercussions. In recent years, affected communities have made some gains, but displacement and disempowerment are still rife.

The exploitation of the Mekong river is only likely to increase. China has a clear energy agenda and Laos aspires to be the “battery of Southeast Asia”. But while exporting much of its hydroelectric power to Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia, the Laotian government imports the same power back at increased cost from Thailand. Local people feel that something is amiss.

Communities from the Mekong villages of Mo Phu and Pak Paew villages have been told to prepare for resettlement due to the planned construction of the Phou Ngoy Dam. They face uncertainty as to the living conditions at their new location.

Development isn’t always positive

The World Bank ranked Laos as the 13th fastest growing economy of 2016, and the Asian Development Bank predicts that its economy will grow at 7 per cent a year for the remainder of this decade.

Hydropower is a major contributor to this economic growth. But hydropower projects promote displacement, put livelihoods and food security at risk, and destroy biodiversity and ecosystems. Without considering both international and local social and environmental costs, hydropower development exacerbates everyday struggles for many people in Southeast Asia.

Many of the destructive projects on the Mekong are supported by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. These powerful international stakeholders should not be above criticism.

The kind of development that is primarily concerned with profits for corporations always occurs at the expense of the most marginalised communities and individuals. All too often their voices are silenced and political accountability is absent.

The evidence indicates that it may not be so simple to decouple economic growth from environmental harm.

Jason von Meding is Senior Lecturer in Disaster Risk Reduction at the University of Newcastle; Giuseppe Forino is a PhD Candidate in Disaster Management at the University of Newcastle, and Tien Le Thuy Du is a PhD Candidate in Geosensing and water management at the University of Houston. This article was originally published on The Conversation.