While Covid-19 lockdown measures in 2020 brought about temporary improvements in air quality and lower greenhouse gas emissions, a pandemic alone has not reversed the effects of climate change in the Philippines.

From back-to-back typhoons in November and extensive flooding due to rising sea levels, the country remains among the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations.

Despite these threats, the government is planning to reduce its commitment to lower carbon emissions under the Paris climate agreement, based on a presentation by the Climate Change Commission to civil society organisations in December.

The commission, whose officials represent the Philippines at the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change’s annual conference of parties (COP), said that the nation is aiming to reduce harmful greenhouse gases by 30 per cent by 2040.

The new target is a retreat from its original pledge in 2015 of cutting by 70 per cent emissions from energy, transport, waste, forestry and industry sectors by 2030, relative to the business-as-usual scenario from 2000 to 2030.

The commission’s vice-chairperson Emmanuel De Guzman said the new plan would “advance our national interest”, but local environmental watchdogs called it “shameful” .

The Philippines was supposed to have submitted its updated targets, known as nationally determined contributions, to the UN by the end of 2020, but has been unable to do so as the commission agreed to “consider the concerns and comments of stakeholders” following last month’s meeting.

In the run up to the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland in November, what will it take for the Southeast Asian nation to ensure that it abides by the Paris accord’s goal to cap global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius? Here are some policies needed this year to steer the country towards a climate-friendly path.

1. Phase out of committed coal-fired plants

The Philippines needs to scrap coal projects in order to contribute to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This includes projects that have been approved, but have yet to be built.

Although the government’s announcement in 2020 that it will stop constructing new coal-fired power plants could stave off over 10-gigawatts (GW) of coal in the pipeline, the archipelago still has 4GW of approved coal projects, apart from the 9.8GW currently installed.

The government’s new policy does not cover applications that have already been endorsed or have secured the needed permits.

Because of the massive expansion of committed coal projects, emissions are likely to peak only by 2035 and an eventual phase-out of coal will only happen by 2062, according to a 2019 report by Germany-based climate science non-profit Climate Analytics. This far exceeds the retirement date set by the Paris Agreement, which sees coal-fired power being phased out in the Southeast Asian region by 2040.

The fossil fuel, the single biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions globally, will account for an estimated 52.3 per cent of the 396.9 million metric tonnes of carbon-dioxide spewed out by the country in 2030, according to the Philippine Energy Plan.

Apart from coal, the country also has to veer away from gas, which accounts for over 21 per cent of its power generation, in order to create more room for renewables in the energy mix.

2. Tap the US$30 billion renewable energy investment opportunity

With the coal moratorium in place, renewable energy investments can be scaled up this year.

The ban on new coal could bring onstream US$30 billion worth of clean energy projects by 2030, revealed a study by global energy think-tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) last year.

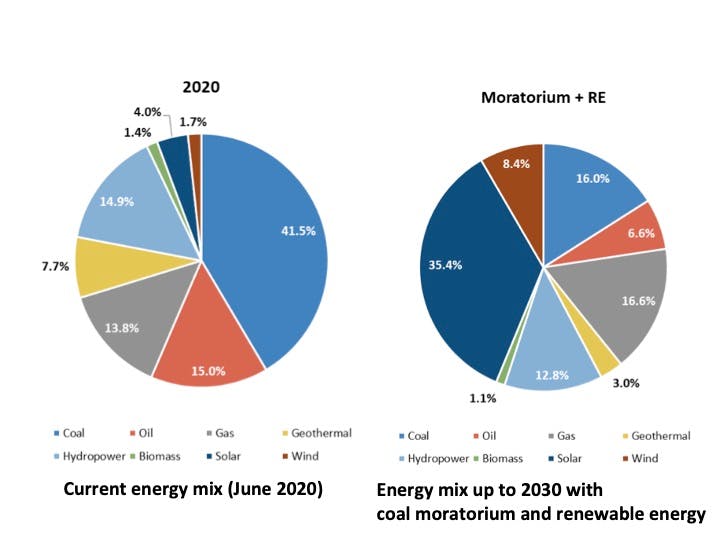

The research noted how coal could be potentially cut to 16 per cent of the energy mix, from the current 41.5 per cent, while the contribution of solar and wind could be increased from 5.4 per cent to a combined 43.8 per cent—a figure that exceeds the government’s projection of 26.9 per cent by 2030.

Local power industry leaders that could boost their clean energy invesments this year include San Miguel Corp. The company may be one of the biggest drivers of proposed coal projects in the country, but is also actively seeking to invest in 10GW of renewable energy and storage over the next decade. The Manila Electric Company, or Meralco’s power generation subsidiary is developing floating solar and plans to deploy 1GW of renewable energy over the next four to six years, while Ayala Corp has 1.8GW of renewables in operation and under construction.

Other players that can benefit from this shift include China’s state-owned enterprises, solar and storage manufacturers, and wind developers across the region, said IEEFA.

Source: Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

3. A national plastic reduction roadmap

With the Philippines ranking third among the world’s top plastic polluters, a comprehensive bill banning single-use plastic packaging and products must be enacted this year.

There have been five bills seeking to ban single-use plastics in the country that have been pending approval since 2018, even as the surge of medical waste from the pandemic has exacerbated garbage woes.

“Major cities in Metro Manila and provinces outside the capital have either banned or restricted single-use plastic, but the Philippines has yet to enact a national law to make local policies more effective,” said Miko Aliño, Asia Pacific programme manager for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA).

Currently, there are over 163 million plastic sachets, 48 million shopping bags and 45 million thin-film bags disposed of daily in the country, acccording to research published by GAIA in July last year.

There are no Philippines-specific estimates for greenhouse gas emissions from plastic, but the global figure could exceed 1.34 gigatonnes of carbon annually by 2030. This is equivalent to more than 295 coal plants with 500-megawatt capacities, based on a 2019 study by United States-based non-profit Center for International Environmental Law.

4. Scaling up funding for nature-based solutions to protect forests

The Philippines can boost investment in nature-based solutions to protect forests and other ecosystems that shield its people from climate-related hazards.

In a country that is hit by an average of 20 typhoons per year—last year’s series of cyclones triggered the worst flooding in 45 years on the island of Luzon—well-managed forests and trees can reduce the impacts of natural disasters.

Experts say that nature-based solutions can provide up to 37 per cent of the emission reductions the world needs by 2030 to keep global temperature increases under 2 degrees Celsius, but such initiatives receive very little funding.

Solutions that the Phiippines could deploy include blue carbon projects like the one spearheaded by non-govermental organisation (NGO) Conservation International that aims to generate carbon credits from the protection of mangroves, which companies or consumers can buy to offset their greenhouse gas emissions.

Grassroots initiatives are another force to watch out for. In Palawan, considered the country’s last ecological frontier, a women-led group is raising funds for replanting of the Almaciga tree as part of efforts by the non-profit Centre for Sustainability PH. The Almaciga is an ancient tree which used to dominate the forests of the northern province. Its high-value resin is equivalent to 80 per cent of the income of the indigenous people who safeguard the area.