India has inexplicably dithered from making dedicated provisions for climate adaptation in its annual budgets, despite facing the brunt of climate change – it was listed as the seventh most vulnerable in the Climate Risk Index 2021. The upcoming budget for the financial year 2023-24 is an opportunity to demonstrate the policy intent towards ensuring climate-resilience of infrastructure, utilising nature-based solutions, and, most importantly, safeguarding the lives and livelihoods of citizens, especially those dependent on climate-sensitive sectors and living in vulnerable regions.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

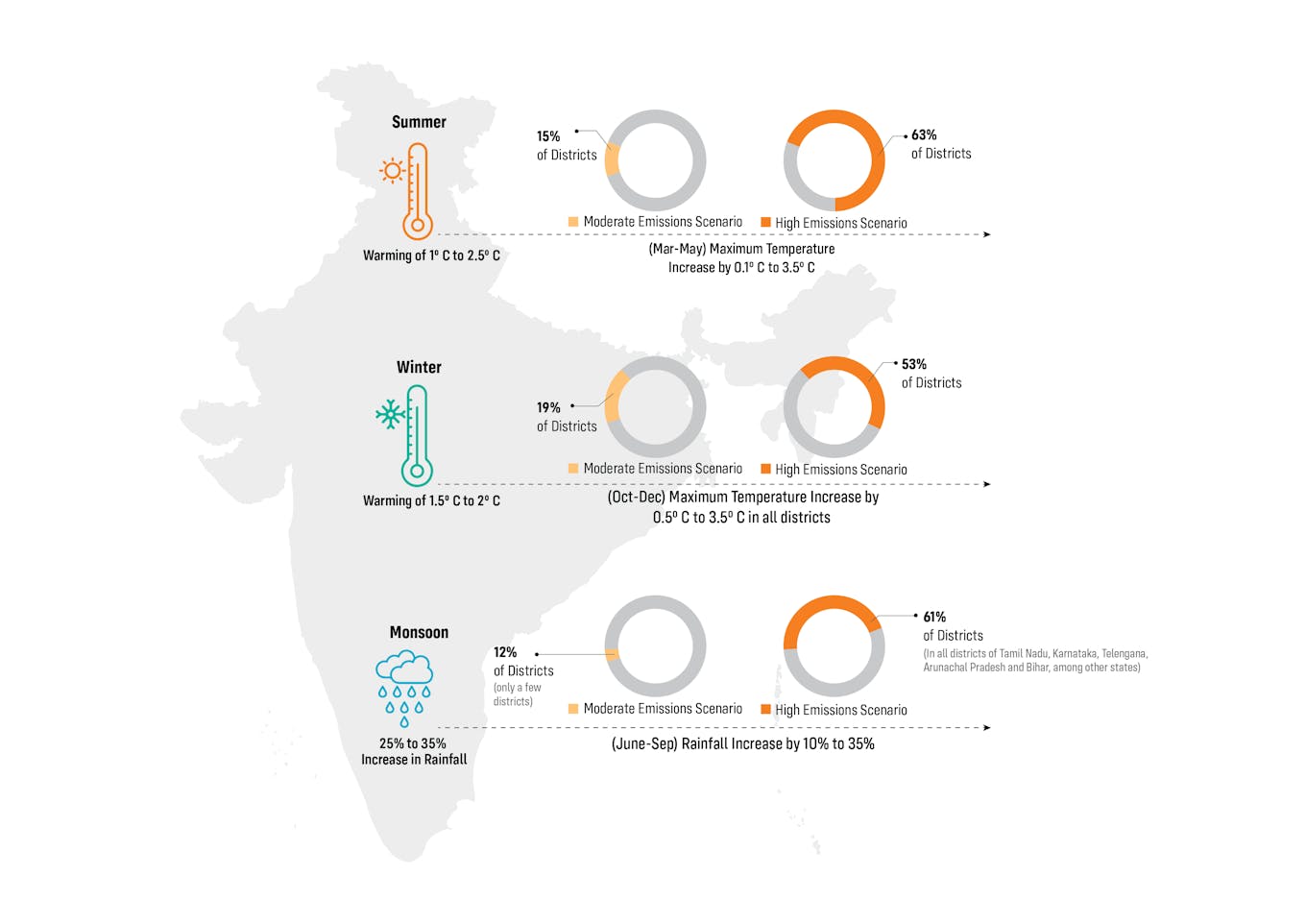

A recent study by the Indian think tank, the Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy, warns that India is staring at a warmer and wetter future. Focusing on the district level across all 28 states of India, the team has analysed climate data from the recent past (1990-2019) and made projections for the near future (2021-2050) under two climate scenarios: moderate emissions and high emissions. It projects that while some districts will be seared by heatwaves in the next 30 years, others will drown because of heavy rainfall and flooding.

Clearly, the budget needs to make a range of allowances for farmers affected by increasingly unpredictable weather, for flood management in cities and towns like the one in Barcelona city, for cooling solutions in regions prone to heatwaves (such as the one in Ahmedabad), for water provision in areas where water availability dries up in the arid season, and so on.

India has been spearheading the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure, climate forecasting and early warning applications. But as recent extreme events have shown, adaptation must take centre stage because while mitigation is essential, it does not address the inevitable consequences of climate change—heatwaves, floods, and droughts, and their impact on climate-sensitive sectors and communities.

The CSTEP study projects that heatwaves – days with temperature departure from the normal of 4.5°C to 6.4°C and higher – will increase in many districts such as the western economic and industrial hub of Ahmedabad, Bikaner in the arid desert state of Rajasthan, the northern industrial city of Ludhiana, and Vellore in southern India. While heat action plans (HAP) are under preparation in over 130 cities and districts across 23 heat-prone states, a dedicated federal budget provision would expedite this process.

Modeling shows that while some Indian districts will be seared by heatwaves in the next 30 years, others will drown because of heavy rainfall and flooding. Image: CSTEP

Since India is urbanising rapidly, requiring construction of residential buildings and city infrastructure at a mammoth scale, policy instruments that promote green urban design as well as energy- and material-efficiency in building and construction are also critical.

On the other end of the spectrum are certain districts threatened by the likelihood of very heavy rainfall events (>100 mm/day), with the potential for flooding during the monsoon season in the years to come. While only 3 per cent of the 732 districts of India recorded such events from 1990 to 2019, 35 per cent to 64 per cent of the districts are projected to record such events under moderate and high emissions scenarios, respectively, in the future. What compounds the problem is that certain districts that historically had no flooding events may receive heavy rainfall and face floods. Further, some districts may face both heatwaves and flooding during the same year.

Here are some areas that deserve priority in the budget:

-

Provisions for enhancing the resilience of farming systems. Nearly 60 per cent of India’s farms (by area) are rainfed, dependent on timely rainfall and its even distribution. Flooding due to heavy rainfall can destroy agricultural crops, with implications for farm incomes and livelihoods. In extreme cases, it can cause the loss of human and livestock lives and livelihoods. While weather-based crop insurance exists in India, the claims paid are according to “pay-outs” as decided by state government notification with respect to the weather triggers. Creating a crop insurance with ‘no claims’ process, which will clear claims on the basis of the realisation of an objectively measured weather variable such as rainfall that correlates with production losses, and roll out of forecast-based financing for social protection is needed.

-

Provisions for coastal insurance to buffer the losses incurred by the 14 per cent of India’s population that resides along its long coastline increasingly battered by cyclones and floods.

-

Conservation and recharge of freshwater resources (only 4 per cent of the world’s resources support almost 18 per cent of the world’s population in India), which will be impacted by extreme heat, floods, and droughts. Heatwaves accompanied by extended periods of no rain, and conversely, heavy rainfall events, affect surface and groundwater availability, with implications for water quality, availability, and management for drinking and irrigation.

-

Planning for the management of heatwaves, which have cascading social, ecological, and economic implications. Extreme heat can cause heat-related illness and death, particularly among outdoor workers and the poor. Further, heatwaves amplify temperatures in built environments, exacerbating the urban heat-island effect.

-

Management of power demand during heatwaves, as well as its implications on labour productivity.

-

Development and preservation of all kinds of infrastructure, since heat as well as flooding can weaken and destroy infrastructure such as communication and power networks, bridges, roads, and railways.

Budget 2023 is an opportunity for the Government of India to provide the necessary policy push for integrated planning toward building resilience in systems – both human and infrastructure.

Indu K Murthy heads the Climate Environment and Sustainability team at the Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy. Vidya S. is a senior analyst in the team