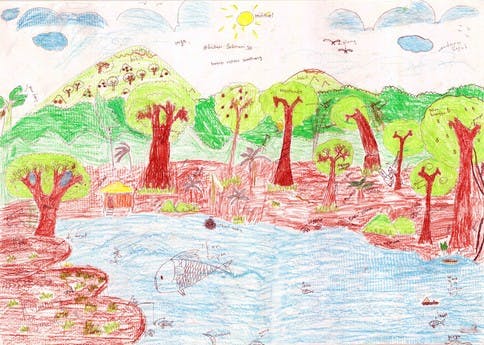

Through the eyes of children, the future of Borneo looks bleak.

To continue watching, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In a newly published study conducted in part by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 247 children between the ages of 10 and 15 living in the Indonesian provinces of East and West Kalimantan were asked to draw the present and future of their environment. The children’s drawings forecast alarming declines in wildlife, forest areas and environmental services.

The research revealed other intriguing results: Children living in the most densely forested landscapes predicted a lower decline in environmental conditions over the next 15 years, with forests, clean water and wildlife largely preserved.

In areas where forests have been heavily cleared, however, children expected wildlife and forests to disappear altogether.

“These children have a strong understanding and awareness of environmental issues and of the interactions between environmental factors,” said Anne-Sophie Pellier, lead author of the research.

“Children often depicted specific human activities to be the main cause of depletion of resources such as clean water, fresh air, fauna, and forest ecosystems. Children also thought this destruction will result in an alarming increase in natural disasters, air and water pollution, and rising temperatures,” she said.

30 per cent of forests lost

The research found that according to the children, the main causes of declining forests and increasing environmental disasters are oil palm plantations, illegal logging, mining and development of roads.

“

Children are the generation responsible for the future condition of the environment and their welfare, it’s important to understand how they perceive it

Anne-Sophie Pellier, lead author of the research

“In Borneo, children are increasingly growing up in human-dominated landscapes which are expanding at the expense of biodiversity and forest services, and [which] negatively impact community welfare,” Pellier said.

The island of Borneo — shared by Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei — has seen high rates of deforestation. A recent study led by CIFOR’s David Gaveau, who was also a co-author of the children study, found that the island has lost some 30 per cent of its forested area since the 1970s, and rapid expansion of agricultural and extractive industries — as well as the roads to support them — are in large part to blame.

The study is part of the Borneo Futures research project, which aims to provide a better understanding of how forests and lands could be more optimally managed on the island.

Capturing people’s perspectives about forest use and values is one of the key research components; researchers use these findings to assess the underlying socio-economic and environmental factors affecting these perceptions. Children’s perceptions are considered an integral part of this research.

“Children are the generation responsible for the future condition of the environment and their welfare, it’s important to understand how they perceive it,” Pellier told Forests News last year.

The most worrisome aspect of the situation in Borneo, Pellier said, is that it could result in a perception of their current degraded environment as the norm (known as “shifting baseline syndrome”). The study seems to show, though, that this is not the case yet, according to Pellier:

“Children seem well aware of what their past environments looked like. And they are concerned.”

Pictures of the forest

In the study, children from 22 villages each drew two pictures — one to illustrate their current impressions of the forest and its wildlife, and another to depict how they imagine it in the future.

“Drawings prove a good methodological means of capturing the perceptions of children especially when they are too shy to write, unable to write or can’t put their thoughts into words,” Pellier said in 2013.

The children’s comments about their drawings were also recorded. They are not encouraging.

“The temperature of the air will become warmer, and there will be no trees to stop soil erosion and floods,” said one.

Said another: “Wild animals will also become extinct because they are too often hunted by people who don’t take their responsibilities, and they’ll lose their home.”

Overall, Pellier said she was surprised about how well children discriminate natural resources and their functions. “Forests give oxygen and provide medicinal plants, fruits, seeds, honey and wood,” explained one group of children.

‘The greatest stake’

The team working on the Borneo Futures project, led by scientist Erik Meijaard, an associate at CIFOR, hope this research will better integrate the voices of local people in government policy-making.

“Understanding what drives environmental views among children and how they consider trade-offs between economic development and social and environmental change could help inform optimal policies on land use,” Meijaard said last year.

The study can also inform education and awareness programs to reinforce positive behaviors toward the environment, Pellier added.

The researchers emphasized the importance of integrating cross-generational perceptions of people into environmental policy and decision-making at local and national levels.

“Children have on average the longest lives ahead of them and the greatest stake in tackling environmental problems to ensure natural resources sustainability,” Pellier said.

“We should listen to them.”

The study, “Through the Eyes of Children: perceptions of environmental change in Borneo,” was published in the open-access journal PLoS ONE.